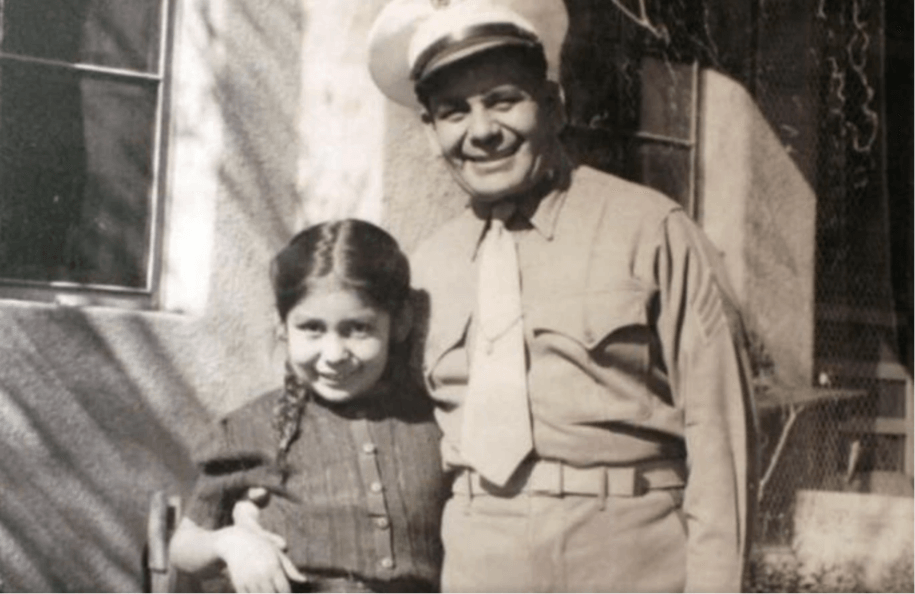

Miguel Trujillo of Isleta Pueblo and his daughter. Trujillo, a World War II veteran, successfully battled state authorities in 1948 for his right to vote in New Mexico nearly a quarter century after Congress extended citizenship to all Indians. Efforts to suppress the Native vote continue today in several states.

Miguel Trujillo of Isleta Pueblo and his daughter. Trujillo, a World War II veteran, successfully battled state authorities in 1948 for his right to vote in New Mexico nearly a quarter century after Congress extended citizenship to all Indians. Efforts to suppress the Native vote continue today in several states.

Vote-by-mail has made it much easier to cast ballots in all elections conducted in Washington, Oregon, Colorado, and California. This approach is also used in some but not all elections in other states as well, particularly in the West. In Arizona, for instance, in 2016, 80 percent of voters mailed in their ballots. No need to go to the polls. Democrats, in particular, view this spreading change as a reform that boosts turnout and is far cheaper to administer than in-person voting. Some lawmakers and activists would like to see the change made nationwide.

But, while vote-by-mail has simplified matters for most voters, when combined with a reduction in the number of polling places and polling hours, it has made things more difficult for many Native voters, especially older ones who live in remote areas without addresses, collect their mail from PO boxes miles away, and need language assistance to understand what and who they are casting ballots for.

As Kira Lerner at Think Progress notes in a lengthy review of the situation, the situation has had a negative impact on some citizens of the sprawling Navajo Nation, the largest Indian reservation in America, with a population of some 175,000 tribally enrolled members.

The circumstances for these Navajo was made considerably worse in 2016 when the Republican-dominated Arizona legislature passed a law prohibiting so-called “ballot harvesting.” Upheld by a federal court last month, the law disallows anyone other than the voter, a household member, relative, or caregiver from delivering a completed ballot to a mailbox or election office. While ostensibly designed as a means of reducing voter fraud, the legislation outlaws professional and amateur get-out-the-vote campaigns to increase voter turnout by making casting ballots easier:

“When people don’t get mail at their homes, how is this going to work?” asked Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, the faculty director of the Indian Legal Program at Arizona State University’s law school. “The census data shows that only one in four homes on the reservation have access to cars and there’s not great infrastructure or public transportation, so it’s likely someone else is going to bring your ballot back to town. Are those people going to be felons?”

Since the U.S. Supreme Court yanked the teeth of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder ruling, states that were originally required to get any new voting laws cleared in advance by the Department of Justice or the courts—“pre-clearance”—have a much freer hand to do as they wish. That has made voter suppression of people of color, including Indians, much easier to get away with than when the act was intact.

Among suppression methods are slashing voting hours, refusing to add polling places on reservations, eliminating language assistance services, and sequestering Native voters in majority-white gerrymandered districts where their political clout is diluted and the chances for an Indian to be elected is reduced or eliminated.

These techniques, while their intent is somewhat more disguised than in the past, are not new.

It wasn’t until 1924 that the federal Indian Citizenship Act accorded all Native American peoples the right to vote. On paper, that is. Ever since, some state and local authorities have done what they can to keep Indians from voting, brazenly at first with their racist roots out there for everyone to see, more surreptitiously as time went on.

In the courts, since the late 1940s, individual Indians and tribes have often prevailed in their efforts to force states to stop this discrimination. However, defeating racist laws and administration actions requires going to court in the first place. This can be an expensive and difficult task. And though Native peoples have won more than 90 percent of these cases, oftentimes new restrictions circumventing the court rulings are soon imposed requiring yet another lawsuit.

From the founding of the Republic, American Indians had been denied citizenship except when they became naturalized, or under special statute or treaty. But to become a citizen and exercise the franchise required Indians to renounce their tribal citizenship, give up their culture and language and assimilate into the dominant culture. In other words, they had to stop being Indians. The Fourteenth Amendment, which gave citizenship and the vote to any male born in the territory of the United States, specifically excluded Indians, just as the original Constitution had done.

It was not until after World War I that the situation began to change. More than 7,000 Indians served in the military during the war. In recognition of that, in 1919, Congress passed legislation that all Indians who had served honorably in the armed forces were granted American citizenship. That, plus the suffragists’ hard-won success at gaining the vote for women, spurred a movement to extend the franchise to all Indians. Under the Indian Citizenship Act—the Snyder Act—all Indians were granted citizenship and with it the right to vote. That should have ended debate on the subject. But it didn’t. Some states continued to deny Indians the right to vote by means of poll taxes, literacy tests, technicalities, and pure intimidation, much like the Jim Crow laws of the South were used to keep black people from voting.

The courts did not affirm the right of reservation Indians in Arizona and New Mexico to vote until 1948 after a Native veteran in each state took authorities to court.

Although it’s not widely known, the Voting Rights Act included American Indians in its mandate, and the 1975 renewal reinforced this. Because of the act, Indians on the Ute reservations of southwestern Colorado finally obtained guaranteed voting rights in all elections in 1970.

This isn’t ancient history. The section of the act gutted in Shelby had been employed in the 21st Century to force state and local authorities to change racist practices curtailing the Indian vote. Here is one instance: While lawmakers squelched the Native vote in several states in spite of federal law, none was quite as bad over the years as South Dakota, a state where there are seven Sioux reservations, collectively known as the Oceti Sakowin, the words in Lakota meaning the “seven council fires.” Slightly more than 8 percent of the state’s population is Indian, concentrated in a few counties.

Having ignored the 1924 citizenship act, South Dakota did not repeal until 1951 its 1903 law requiring a culture test for Indians to prove they had abandoned their identity as Indians, their culture, their language and their homeland in order to vote or hold office. As late as 1975, authorities prohibited Indians from voting in elections in the counties of Todd, Washabaugh, and Shannon (Ogala Lakota County since 2015), whose residents are overwhelmingly Indian. The state also prohibited residents of these counties from holding county office until as recently as 1980. But South Dakota continued suppressing Indian voting rights decades later.

The state’s Republican attorney general and notorious Indian-hater, William “Wild Bill” Janklow, was infuriated. In a formal opinion addressed to the secretary of state, he derided the 1975 amendment and called the Voting Rights Act itself an unconstitutional federal encroachment that rendered state power “almost meaningless.” He quoted Justice Hugo Black’s dissent in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (which held the basic provisions of the Voting Rights Act constitutional), saying that Section 5 treated covered jurisdictions as “little more than conquered provinces.” A remarkably ironic assertion given the long history of U.S. and South Dakota double-dealing with the tribes. Meanwhile, Janklow advised the secretary of state in 1977 not to comply with the pre-clearance requirement.

While such blatant racist suppression is much rarer these days, it doesn’t mean the practice has entirely disappeared.

Jim Tucker, an attorney and member of the Native American Voting Rights Coalition, told Lerner at Think Progress:

“The overall, dominant theme of barriers that you see in Indian County are the sort of barriers that federal legislation including the Voting Rights Act was intended to eradicate […] They are just entrenched in many parts of the country and it makes it much more difficult to bring litigation because there’s no simple, magic bullet fix now. You have to address many, many different issues in order to provide equal opportunities to participate and elect candidates of choice.”

Patty Hansen, who administers elections in Coconino County, Arizona, where a fourth of the eligible voters are Navajo, says:

“There needs to be … a reconciliation — which is obviously a huge order, between tribes and their local communities — and an acknowledgement and an acceptance and an encouragement of participation […] If the community can vote consistently, you can start to get attention and Native communities can represent a statistically significant group, especially in some of these elections that aren’t won by very many votes.”

A few sources for further exploration:

American Indians and the Fight for Equal Voting Rights (2011).

Voting Rights in Indian Country: A Special Report of the Voting Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union (2009)

A history of U.S. voting rights and why it is important to vote (2012)

U.S. vs. Blaine County Montana (2004)

Fremont County Case (2012)

Navajo Nation v. San Juan County Utah (2017)

Leave a Reply