For the Plains Indians, the buffalo (technically bison) was more than an important source of food, shelter, and clothing: the buffalo was also an important spiritual and cultural symbol. At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were an estimated 30 million buffalo roaming the Great Plains. A century later, in 1900, the buffalo had become an endangered species. At this time there were only 500 buffalo left.

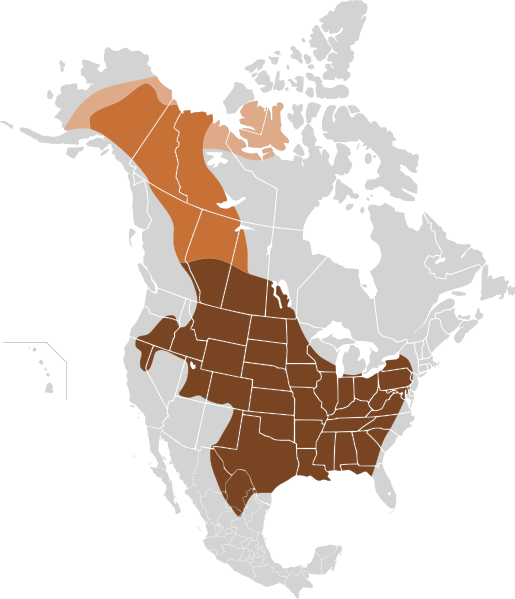

The aboriginal distribution of the Plains Bison and the Woods Bison is shown above.

Shown above is a Catlin painting of an Indian buffalo hunt.

Direct Genocide:

The near genocide of the Buffalo People was brought about by the actions of non-Indians, often purposefully intended to bring about the extinction of the species and with it, it was hoped, the extinction of Plains Indian cultures.

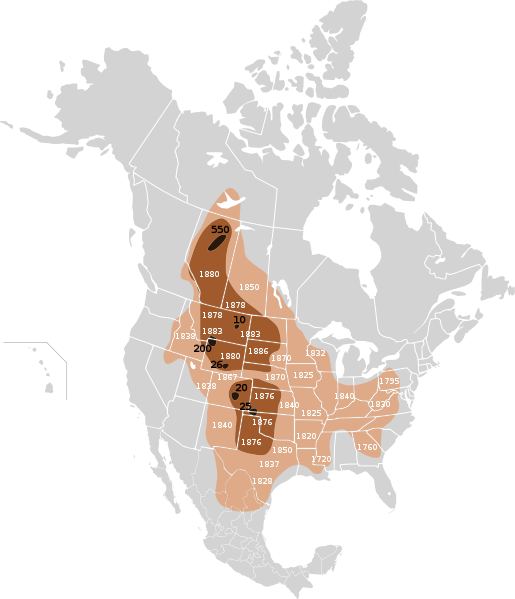

The nineteenth century extermination of the buffalo is shown above.

Many American officials, particularly those in the military, saw a direct correlation between the extermination of the buffalo and the extermination of Indians. Thus, many advocated the genocide of the Buffalo People as a way of conquering the Indian nations of the Great Plains. In 1869, for example, General Sherman wrote to his superior, General Philip Sheridan, and suggested that sportsmen from the United States and England be encouraged to come out to the west to shoot buffalo.

In 1870, American hunters armed with Sharps breech loading rifles killed an estimated two million buffalo. Colonel R. I. Dodge noted: “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” The buffalo population dropped to an estimated 7 million.

Testifying before Congress in 1871, Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano said:

“I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect upon the Indians. I would regard it rather as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil and their own labors.”

On the Southern Plains, non-Indian buffalo hunters (known as “runners”) were crossing into Comanche territory to hunt and the army did nothing to stop them. In fact, the army had adopted a proactive role in the destruction animals and was supplying the runners with equipment and ammunition.

In testimony regarding a bill to protect the buffalo, General Sheridan told a joint session of the Texas legislature in 1875 that buffalo hunters “have done in the last two years and will do more in the next year to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last thirty years” His recommendation:

“for the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffalo are exterminated.”

In the debate over the buffalo in Congress in 1876, the administra¬tive position was stated by Representative James Throckmorton of Texas:

“There is no question that, so long as there are millions of buffaloes in the West, so long the Indians cannot be con¬trolled, even by the strong arm of the Government, I believe it would be a great step forward in the civilization of the Indians and the preservation of peace on the border if there was not a buffalo in existence.”

In 1882, a buffalo herd of an estimated 75,000 animals crossed the Yellowstone River near present-day Miles City, Montana. Passengers on a steamer shot the animals until the river ran red with blood. Fearing that the herd might reach Canada and be utilized by Sitting Bull’s Lakota, the army issued free ammunition to those who wished to shoot the animals. Only 300 animals reached Canada.

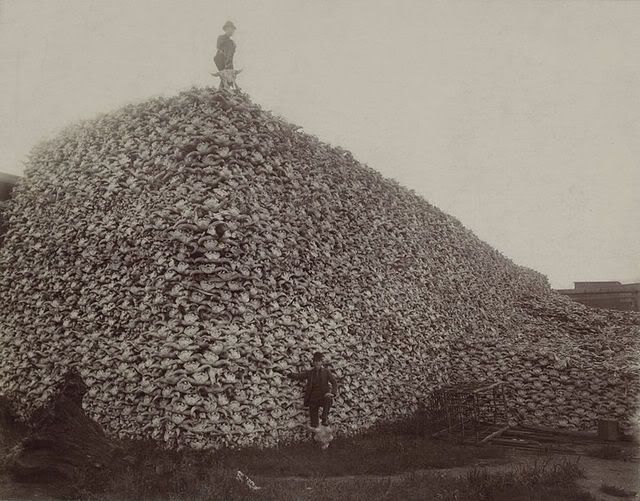

A pile of buffalo skulls from animals killed by non-Indian hunters seeking to exterminate the species is shown above.

Indirect Genocide:

Part of the near genocide of the Buffalo People stemmed from the unintended consequences of the fur and hide trade. While the fur trade had begun during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with a focus on furs and on beaver pelts, by the early nineteenth century the focus was changing toward hides, particularly buffalo hides. Since buffalo hides now had value as a trade item, this changed the relationship between the Indian people and the Buffalo People. By 1835, there was a greater demand for buffalo hides than for fur pelts in the international trading markets.

Traditionally, Indian hunters had taken buffalo and had used the entire animal-hide, meat, horns, hoofs, and intestines. This had been a sustainable relationship which was celebrated in the Indian religious and spiritual traditions. The European traders, however, introduced Indian people to a globalized market in which they could obtain manufactured goods by trading buffalo hides. Before long, the desire for the manufactured goods overcame spirituality and buffalo were killed only for their hides. This ended the sustainable relationship between the Indian People and the Buffalo People.

The buffalo robe trade from the Missouri Valley generated an estimated $50 million. The production of buffalo robes by the Indians was limited by two things: (1) the number of animals which could be killed by the hunters, and (2) the number of hides which the women could process. The average number of robes which could be processed by a single woman during the winter was 18-20 with some doing as many as 25-30.

The buffalo hide trade changed women’s roles within the tribes. More of their time was now engaged in the production of buffalo hides for trade. It would take about 80 hours of work to prepare a hide for trade and the hide would bring the Indians $1.50 to $2.50 in trade goods. This meant that the women were earning about 2 or 3 cents per hour for their work.

In 1871, tanneries in the United States and in Europe developed a new method for processing buffalo hides as leather, thus creating more demand for buffalo hide. As a result of this new process, the slaughter of the animals was no longer restricted to a particular season.

With regard to the buffalo hide trade in 1876, 155,000 hides were shipped from Montana; 170,00 were shipped east via the Santa Fe Railroad; and 200,000 were shipped from Fort Worth Texas. Since not all of the buffalo had usable hides, these 550,000 hides probably represent the killing of more than a million buffalo.

Saving The Buffalo People:

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a number of people, both Indian and non-Indian, were concerned about saving the buffalo. In 1874, Congress voted overwhelmingly to stop the slaughter of the buffalo on the plains, but the bill was pocket vetoed by President Ulysses S. Grant. There are conflicting theories about what Grant actually did with the bill. Some historians feel that he received the bill and then put the document into a pigeonhole for its India ink to become a rich brown before it was seen again. There are others who feel that he used it for lighting his cigar.

The noted zoologist and buffalo authority William T. Hornaday wrote in 1887:

“The wild buffalo is practically gone forever, and in a few more years, when the whitened bones of the last bleaching skeleton shall have been picked up and shipped East for commercial uses, nothing will remain of him save his old, well-worn trails along the water-courses, a few museum specimens, and the regret at his fate.”

While zoologists and Congressmen were lamenting the passing of the buffalo, there were a few Indians and others who were trying to do something to save the Buffalo People. In 1871, Walking Coyote, a Pend d’Oreille from the Flathead Reservation in western Montana, killed his wife-some say he killed her because of the furies in his head-and then fled across the Rocky Mountains to the Blackfoot. While living among the Blackfoot he took a Blackfoot wife, but he still found that he missed the mountains of the Mission Valley. Noticing his deep melancholy, some of the Blackfoot suggested that he might capture a few buffalo and take them back to the Flathead Reservation as a kind of peace offering. Since there were no buffalo on the Flathead Reservation, he might be forgiven for his crime and welcomed home as a hero.

Walking Coyote joined a Blackfoot hunting party along the Milk River where it crosses into Canada. After a successful hunt, a dozen stray motherless buffalo calves grazed alongside the horses in Walking Coyote’s camp and followed the hunters around. Walking Coyote then returned in 1872 to the Flathead Reservation, bringing some of the calves with him to start his own herd.

The following year a man known as Samuel Welles or Indian Sam brought four buffalo calves from the Plains area across the Rockies to the Flathead Reservation. Elder Que-que-sah recalls:

“Buffalo hunting had ended owing to the fact that the herds had all been killed. We were all greatly interested in the welfare of Samuel’s calves. I think that every Indian upon the reservation looked upon this little herd as the last connecting link with the happier past of his people. I know we all protected them, wherever they were grazing.”

On the Flathead Reservation in Montana, Charles Allard and Michael Pablo started their own buffalo herd in 1884 with animals purchased from Walking Coyote. They later added some additional buffalo which had been raised with cattle.

In 1893, part of the Allard-Pablo buffalo herd was driven to Butte where they were exhibited for a week. As entertainment for local residents, a kind of rodeo was put on in which cowboys rode the buffalo. An additional 46 buffalo which Charles Allard had purchased from “Buffalo” Jones were shipped from Nebraska and joined the Flathead herd in Butte. There were some battles between the bulls of the two herds.

When Charles Allard died in 1896, the buffalo herd was broken up. Michael Pablo retained 150 head.

Raising buffalo on the Flathead Reservation was not encouraged by the government. In 1900, 27 buffalo from the Allard-Pablo herd were purchased by banker and entrepreneur Charles Conrad. Conrad, who had a Blackfoot wife and family in addition to his non-Indian wife and family, purchased the herd because he felt that the buffalo were near extinction and wanted to support the propagation and perpetuation of the species.

In 1902, 21 buffalo from the Allard-Pablo herd were purchased by Yellowstone National Park.

National Bison Range:

President Theodore Roosevelt established the National Bison Range near Moise, Montana on the Flathead Reservation in 1908. The mission of the National Bison Range is to provide a representative herd of buffalo, in natural conditions, to help ensure the preservation of the species for the public benefit and enjoyment. While the Bureau of Indian Affairs discouraged buffalo on the reservation, it freely gave up reservation land for the new Bison Range. As usual, the Indians were not consulted in this transaction.

The following year, 34 buffalo from the Conrad herd (which had been the Allard-Pablo herd) were purchased by the American Bison Society and placed on the National Bison Range. Thus, the buffalo which had been discouraged by the Bureau of Indian Affairs came home to the Flathead Reservation.

By 2003, the American government was interested in getting out of the business of government through a process known as privatization. At this time, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes of the Flathead Reservation once again expressed their desire to manage the National Bison Range at Moise. Under the 1976 Indian Self-Determination Act the tribe could assume management of federal programs within the reservation. While the tribe had successfully assumed management of other programs, the Department of the Interior had been reluctant to give up management of the National Bison Range. The Fish and Wildlife Service had managed the Range as a wildlife refuge. In 2004, the tribes signed an agreement with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to assume management functions at the National Bison Range Complex. The tribes were to take over the responsibility for five activities: administration; the biological program, including habitat management; fire control; maintenance; and visitor services. Ownership and overall management authority was to remain with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The tribal take-over of the management of the National Bison Range was vigorously opposed by non-Indian groups and by members of the Montana Congressional delegation.

In 2006, the Fish and Wildlife Service took the management of the National Bison Range away from the tribes citing concerns over the tribes’ ability to manage the facility. Many observers, both Indian and non-Indian, felt that the tribes had been set up to fail and had not been given adequate support for the transition. In 2008, the tribes resumed management. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director H. Dale Hall stated:

The Bison Range occupies a special place in the hearts of Tribal members. I know the passion that they have for the land of their ancestors, and for the wildlife that sustained them. Fish and Wildlife Service employees also care passionately about the future of the Bison Range, and I strongly believe this agreement will serve to bring everyone together to accomplish great things for the refuge.

Buffalo Commons:

In 1987, Frank J. Popper and Deborah Popper published an essay in which they pointed out that current use of parts of the Great Plains is not sustainable and suggested the creation of a Buffalo Commons: an area of 139,000 square miles in which the buffalo or American Bison could be reintroduced. There is strong opposition to this idea from non-Indians who feel that land must be developed and modified from its aboriginal form.

Inter Tribal Bison Cooperative:

In 1992 the Inter Tribal Bison Cooperative was started to help the tribes with their buffalo herds. At the present time, it has 57 tribal government members in 19 states. Since 1992, the number of buffalo on Indian lands has tripled.

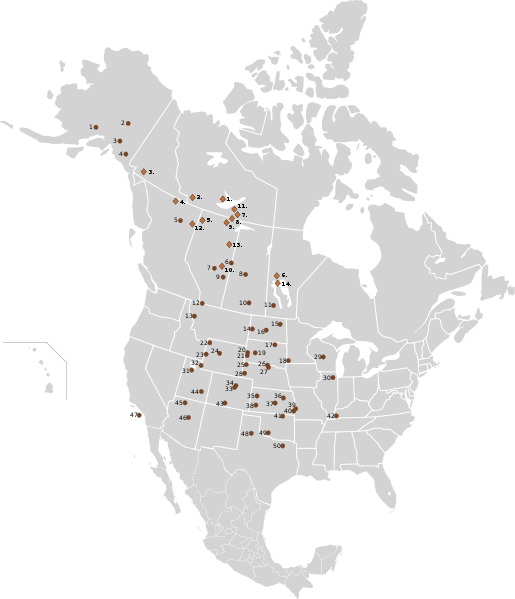

The current distribution of bison herds is shown above.

Leave a Reply