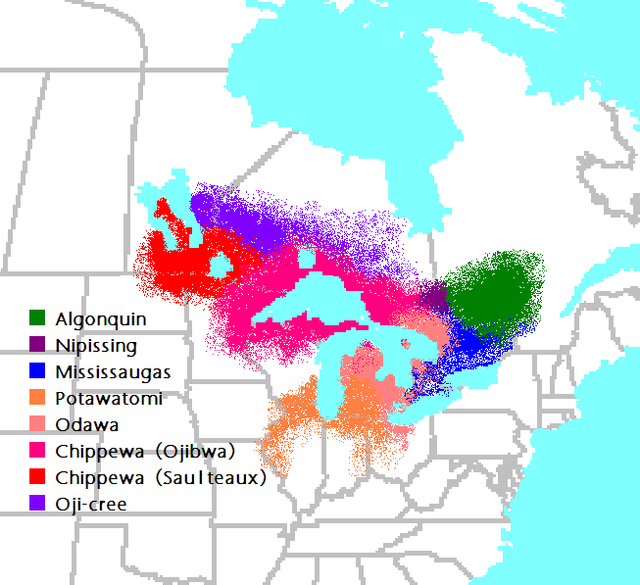

The western portion of the Great Lakes area was inhabited by Algonquian-speaking tribes such as the Anishinabe (Ojibwa or Chippewa), Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Menominee, Shawnee, Ottawa, and Sauk and by Siouan-speaking groups such as the Winnebago, Iowa, Oto, and Missouria. The Siouan-speaking groups probably emerged from the Oneota cultural tradition that began to flourish about 1000 AD in the upper Mississippi Valley.

Fish were a major portion of the Indian diet. The archaeological record shows that Indian people in the western Great Lakes area used a wide variety of different kinds of fish. These included suckers, catfish, and sunfish.

Among the Algonquian-speaking Indian nations in this area, fishing was a year-round occupation, but at certain times the fish were more plentiful than at others. During the spring and fall, when the fish crowded into shallow water, the Indians caught them by the thousands. During this time, when there were plenty of fish to catch, the bands lived in fairly large groups on the shores of the Great Lakes.

Among the Anishinabe of Minnesota, families would move to their fishing grounds in mid-October. Here they would catch fish to last them over the winter. At some sites, such as Sault Sainte Marie, where fish were abundant, the Anishinabe would remain at the fishing site during the winter. One of the important fish at this site was the whitefish. Some groups would make regular or irregular trips to the fishery at Sault Sainte Marie in the fall.

Fish were taken with fishhooks, nets, spears, traps, lures, and bait. It is important to understand that this was not sport fishing: it was a subsistence activity which was vital to the survival of the people. The focus was on harvesting as many fish as possible in a relatively short time.

Many tribes, such as the Chippewa and Ottawa, used gill nets for fishing. Working with basswood, nettle, and other natural fibers, the women would fashion mesh nets. The men would then make cedar floats for the net and they would cut grooves in small stones which would serve as sinkers.

In many of the tribes, the women would set nets made of basswood and twine. With this system, they would catch as many as 200 fish in a night. The nets would then be washed and cleaned with a sumac leaf solution to get rid of the fish odor. Herbal medicines would then be applied to the net to attract the fish.

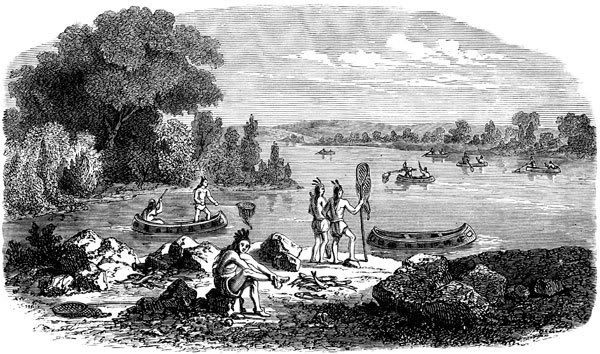

On the rivers, the Indians would often fish from a canoe using a dip net. Two men working from a canoe could harvest several hundred pounds of fish in just a few hours. The man in the bow would handle the net while the man in the stern would guide the boat in a backward drift downstream. At Sault Sainte Marie, a bark canoe would be paddled out into the rapids. One individual would then stand up and thrust a dip net deep into the water to catch the fish. Typically, six or seven large fish would be obtained with each dip. The fish would be dumped into the canoe and the operation repeated until a full canoe-load of fish had been obtained.

On the Great Lakes, the fishermen would take their canoes far offshore and set their nets in deepwater.

In addition to using the nets, fish would also be speared at night using a birch-bark or pine-pitch torch. The light from the torch would draw the fish to the area around the canoe where they could be easily speared. The fishing spear was usually tipped with a bone or horn point.

In some places, the Anishinabe used fish traps. Rocks would be piled across a small stream to form a V. This would form a trap to bring the fish into the small area of the V where they could be easily caught. John Rogers, recalling his Anishinabe boyhood during the 19th century, writes:

“Later, when we had no use for the trap, it was removed from the river. The fish must not be caught except for eating, for such is the belief of the Chippewa and other Indian tribes.”

During the winter, Indians would spear trout and sturgeon through the ice. They would first cut a hole in the ice and then build a small hut so that the fisherman would be out of the light, hidden from the fish. The fisherman would drop a small lure into the water and use it to decoy the curious fish into spear range. In some instances, they would use spears up to forty feet in length to reach into the depths of the water. Sometimes they would use gill nets when fishing through the ice.

The fish would be processed by smoking and drying. In colder weather, the fish would be frozen for later use.

One of the ways of preparing the fish among the Anishinabe was to carefully pack the fish in clay and then bury it in the coals of the fire. After several hours the fish would be ready to eat. John Rogers, writing in the 19th century, recalls:

“…when they were taken from the fire and clay, the scales would cling to the clay, so the fish were all ready to eat. And, oh, how delicious they were!”

Leave a Reply