Welcome to the 14th edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the “Invisible Indians” project put together by Meteor Blades and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Last week’s edition is here. In this edition you will find my personal account of living in two worlds, a look at the years 1541 and 1885 in American Indian history, four news briefs and some linked bulleted briefs. Click on any of the headlines below to take you directly to that section of News & Views or to any of our earlier editions.

This Week in American Indian History in 1541 and 1885

~

Killing of White Buffalo Seen As Possible Hate Crime ~ Indians Plan Rally Over Racist Attack on Blind Lakota Man ~ Samuel Tso, VP of the Navajo Code Talkers Association Has Walked On ~ U. of Minnesota Students Produce Film Calling for Apology to Dakota Indians ~

By navajo

I am trying to live in two worlds.

I was born in Utah. My white father descended from the Mormon pioneers. His grandparents were polygamists. My full-blood Navajo mother – who was taken from her family at age five to be assimilated into white culture at the Tuba City Boarding School – joined the Mormon church in her 20s.

Mom had the typical boarding school experience. Overwhelming homesickness, having her mouth washed out with soap for accidentally speaking forbidden Navajo, witnessing others endure severe punishment for being incorrigible in some Navajo way and a constant curriculum of You Need to Become White Now. My mom was smart, she learned fast to conform, to survive. She excelled at the school and even skipped grades.

Many of her supervisors there were Mormon and the church also had a strong presence on the rest of the Navajo reservation. It was everywhere. Mom eventually served a two-year mission for the church, doing her work among the Zuni. When she completed her mission, the local paper, the Richfield Reaper, reported her accomplishment. Someone mailed the announcement to my father because he had an interest in Indians and a strong love of the church. He was so impressed that she had devoted two years of her life to the church while leaving her three-year-old son with friends. Her first husband, another Navajo, had been killed at a young age. My dad wrote her a letter and asked to meet her. Later they married and started a family in rural Utah.

Being Indian, being Navajo, is one world. I’ll get to that shortly.

The majority of my life was spent living in the world of white where I often hid my real blood by altering my appearance as best I could. All around me was a common attitude that my brown skin made me inferior to the white townfolk. See my essay Born Evil for my experience growing up as a “Lamanite.” That’s what the Mormon church still calls Indians. In those days not so long ago, it went further and called us fierce, bloodthirsty, lazy, idolatrous and loathsome because God cursed us with dark skin. In that essay you can read about my being told in public that I was not preferred by God the way my white Sunday school classmates were. And that I must work hard to make up for it.

The common belief system supported directly by the Book of Mormon and emphasized by public comments from the leaders of the church fostered an attitude that being “white and delightsome” was superior in the eyes of God. Thus white was the preferred skin color in the community as well.

It was hard growing up where I was considered a second-class citizen, even by Utahns who were non-Mormon.

There are two reasons my memories have come flooding back now. The news about Senate candidate Elizabeth Warren in which her alleged “Indianness” has been made an issue and the bullying by presidential candidate Mitt Romney.

The right-wing’s instant response regarding Warren’s claims of a Native heritage was to make fun of her by slurring Indians with a flurry of insults using stereotypes and calling her “Pinocchio-hontas,” “Faux-hontas,” “Chief Full-of-Lies,” “Running Joke” “Sacaja-whiner” and “Spreading Bull.” A name like Sitting Bull should be treated with respect. Why is this the first thing people think to do when they want to make fun of Indians?

The slurs reminded me of the same sad treatment I received as I was growing up.

In 1973, after the American Indian Movement and Oglalas on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota took over the village of Wounded Knee, my bully of a high school political science teacher, who was also the football coach, took to calling me Wounded Knee in class. Every time I raised my hand to ask a question he would say, “Oh, Wounded Knee has a question!” I was deeply annoyed but did not want to draw more attention to myself, so I did not respond publicly with anger or sadness. I went on as though nothing had happened. Fortunately, the majority of my classmates were fond of me and did not themselves adopt this racist dig of a nickname. They also never used the slur “half breed” to me.

But when I was nominated to be homecoming queen the next year, I knew that that fondness had its limits. No way would I be chosen since I was running against two of the prettiest and most popular girls in my class. White girls. I was certain one of them would win. I was honored just to have been nominated. That was enough for me. The three of us were called on stage during an assembly to announce the new queen. I wondered which of them would be chosen. Then my name was announced! I couldn’t believe it. The other two burst into tears. Like me, neither of them thought I would be chosen. As I looked out into the cheering audience, I saw why the three of us had misjudged. All the Navajo Dormitory students were jumping up and down with huge grins. They were the students separated from their families and brought to town from all over the Navajo Nation to have the Indian taken out of them in the Richfield schools. My mother worked in the cafeteria at the Navajo Dormitory. I had forgotten the alliance I would have with those students. I had the swing vote!

Another time I felt very unsafe. The sheriff’s son, who was a senior when I was a sophomore, said harshly and menacingly close to my face, “Ho.” For NavaHO. That’s what jerks like him called all Indian students in town: Hos. This was well before the word was slang for “whore,” as it is today, so that was not his intent. But it was meant to be derogatory. I stayed away from him after that. Fifteen years later I was in my hometown with my young daughters at a restaurant. In walks the guy, and I see that he’s now the sheriff! I quietly grabbed my girls, got in the car and left town. I saw his gaze follow me as we left. He seemed to being trying to place me. I checked my rearview mirror several times on the way to the freeway. I’m always afraid of lawmen in small towns.

When I finally started to pursue a career, I found I advanced faster if I didn’t dress to match like my ethnic background. Dressing with Indian elements was viewed as a caricature, as if I were wearing a costume rather than expressing ethnic pride. In the workplace my ethnic clothing and jewelry were met with raised eyebrows. I got the distinct impression I needed to dress more conservatively, to fit in better. And I did. I tried to look as white as possible. I cut my long brown hair very short. I didn’t wear any Navajo jewelry.

Decades later, I finally took a break from working as a result of too much travel and burnout. It was during that quiet interlude I found that I regretted not having embrace my Indianness and especially regretted that my daughters didn’t know much about their heritage. I made a concerted effort after that to take regular road trips to the reservation with my daughters so they could meet their relatives and taste the wonderful, rich culture. I wanted them to feel a part of the reservation even though they are assimilated.

I’m also assimilated. Born and raised off the reservation, never taught my Native language and existing more or less comfortably within the dominant culture. I’m invisible to non-Indians, so we get along well. In the past few years, I have made strong statements with my appearance, but no one ever asks if I’m Indian. They just assume I’m of the hippie culture that is very much alive and well here in urban Northern California.

Now for that other world.

In spite of my Navajo grandparents having to give up their children to the government-run boarding schools to have the Indian removed from each child, our extended family miraculously retained its culture. My grandparents plotted to hide half their children from the Bureau of Indian Affairs kidnappers in the deep canyons of Inscription House on the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona. Those kids did not learn English and they kept to the traditional lifestyle of living in hogans without electricity or plumbed water. Shi cheii (the term meaning “my maternal grandfather” in Navajo) was a renowned medicine man. He passed on his hathalie (healing and spiritual) knowledge to his eldest son Robert. I became very close with my Uncle Robert in his last few years. That’s another story I’ll tell another day.

In the previous century, my mother’s ancestors defeated one of the myriad government actions meant to destroy our culture. In 1864, thousands of Navajo were forcefully removed from their lands and force-marched almost 300 miles away to Fort Sumner in New Mexico. Fortunately, the tribe was able to return four years later, but it was devastated by the trauma of incarceration. Our family was lucky. They were able to hide deep in the canyons and high on top of Navajo Mountain. They did not go on The Long Walk. But it was still difficult for them to endure this wartime atmosphere and recover from it. In order for the Navajo to return to their lands they had to sign a treaty with many demands. One was that all the children would be given up to the government boarding schools to be assimilated. That led to the boarding school experience my mother survived. Her older sister Zonnie didn’t survive.

Because this family culture wasn’t destroyed, my mom’s Navajo roots remained strong. She visited her family on vacations and she remained steeped in the culture. She maintained fluency in the language. She took us along for several weeks every summer to herd sheep, enjoy the wonderful food, play with our cousins and live in the traditional style. We watched shi cheii perform ceremonies. I treasured every moment on the Rez.

However, years earlier when my mom was at boarding school, she was advised to marry a white man and not teach her children the Navajo language. She was told this would raise her out of poverty and not hold her children back from advancing in the white world. It was curious that with such a strong cultural background that my mom followed this terrible advice. I think it points to how forceful the directives were from the government and how much of a survival instinct my mom had.

She felt that she was doing the right thing for us.

I admire non-English speakers who immerse their children in their mother tongue. As a result, as adults they can communicate more broadly and understand other cultures in ways monolingual people cannot. Sadly, neither I nor my siblings are fluent in Navajo, a result of the government assimilation policy and a compliant Indian woman who took the path of least resistance in her struggle to get by, to fit in.

I pay a price for not knowing the language when I visit my relatives on the Rez. Every time I go, I’m completely left out as my relatives converse in Navajo. I have to patiently wait for someone to translate for me. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve asked for a translation and no one could go back that far in the conversation to help me out. And then the talk forges on while I sit in the dark.

Once, a few years ago at a family reunion for a traditional Navajo marriage, my cousin said deliberately within earshot of me, “Well, we are certainly getting whiter and whiter every time we get together …” I felt unwelcomed by him. The same cousin later laughed when I tried to pronounce a word in Navajo. Another time I asked a question of my Uncle Robert and this cousin interrupted: “We don’t share our stories with outsiders. You can ask all the questions you want but we won’t answer them.”

So here I was, again in the same situation I dreaded in the white world. Not fully accepted in either world. Half breed.

But my uncle Robert, who usually sat quietly and merely observed, slowly started to speak, in Navajo. He spoke a long time with many hand gestures indicating distance, of travel. When he finished, this cousin, his son, sat silent. Everyone sat silent. When I realized no one was going to fill me in without prompting I asked what had just been said. My cousin Judy said that Uncle Robert had told his son that I was not an outsider. He had described the story of how I found him and reunited him with my mother, his sister he had not seen for 30 years. There’s much more to that story, one I’ll tell another day. Uncle Robert told his son I was blood and that I should be included. His son stood down and sat quietly the rest of the visit.

So in both worlds, there are inclusive people and exclusive people. Fortunately for my mental health there were many more nice people than mean ones. But the adverse experiences take a toll, especially on a young heart and mind.

One tends to never forget them.

By Meteor Blades

On May 8, 1541, on a fruitless search for gold and other riches, the thief, slaver and conquistador Hernando de Soto reached the Mississippi River somewhere south of present-day Memphis, Tenn. About a month later, having built crude boats, he and the remaining 400 men of the expedition that had begun in Florida two years before managed to evade the patrols of Indian war canoes and become the first-known Europeans to cross the great river. From there, they wound through what are now Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas. In a year, de Soto would be dead.

Another Spaniard took his place and continued the expedition. But the Spaniards had lost more than half their number, including their translator, a slave whose death made communication difficult with the Indians they encountered everywhere they went. They were harried by warriors constantly. They could not find enough food after having consumed most of their horses and all of the 200 pigs they had brought with them (except for those that escaped to form the ancestors of the razorback population of wild hogs now prevalent throughout the South). Most of all they could find no gold or silver. It was decided to pack it in and head back to the Mississippi and eventually to Mexico City. When a further expedition into North America was announced there in 1545, almost none of them signed on.

Even in that era, de Soto was considered a brutal man. Born and raised in the northwest Spanish province of Extremadura, a region of poverty that spawned many conquistadors, he first came to the “New World” in 1514 at age 17. He gained a reputation for loyalty and cleverness in the conquest of Central America and became wealthy in the Indian slave trade. He was made governor of Cuba and gained estates in Nicaragua and Guatemala worked by Indian slaves. But he longed for greater success and finally was sent on his own expedition to Yucatan in 1530 to hunt for a passage to China, the quest that Spain had been on for four decades. He did not succeed. But in 1532 joined Francisco Pizarro for the conquest of Peru. From the loot of that slaughter, de Soto became fabulously wealthy and returned to Spain, married well beyond his social station to a relative of someone close to the queen and seemed set for life.

But he was soon restless and champing at the bit for another adventure and more gold. That’s when the North American expedition was hatched. And, according to what we know now, that was when the fate of the Mississippian culture of the Southeast was sealed. De Soto’s three-year trek from village to village, sometimes trading peacefully, sometimes fighting, as they did at the Battle of Mabila – Mobile, Ala., takes its name from that one – under Chief Tuskaloosa. They won the battle and burned Mabila. But it was a Pyrhhic victory. By the time they reached the Mississippi, de Soto’s original expedition was in a bad way, its crossbows no longer working, the horses gone, the heavy armor cast off and most of the survivors of the trek weakened and diseased.

They were spreading disease, too. The populace in towns and forts throughout the region was dense and diverse, agriculture abundant, culture sophisticated. The next time Europeans would encounter the region, it was depopulated, having been wiped out by the germs the Spaniards brought with them. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people who had never seen a European lost their lives to them as smallpox and other diseases against which they had no immunity took out as much as 90 percent of village after village. That kind of plague destroys more than people. It obliterates entire societies, which is exactly what happened.

Because de Soto had assured the Indians he was an immortal deity related to the sun, when he died of fever on May 21, 1542, his men weighed his body down with sand and secretly deep-sixed him in the Mississippi.

On May 12, 1885, the Metís of Canada surrendered and brought an end to the Second Riel Rebellion. The Metís were people of mixed European and Indian blood, often with French (sometimes Scottish or English) fathers, and mothers of one of several First Nations tribes, mostly Cree, Ojibwe, Saulteaux or Miqmaq.

The Francophone Metís were increasingly upset about an influx of Anglophone settlers and the impending transfer of land from control by the Hudson Bay Company to Canadian sovereignty. They had no title to the land and feared they would lose their de facto control of it under the new arrangement. They were led by Louis Riel. He first spoke out publicly in early October 1869 – saying that nothing should be done before Ottawa negotiated with the Metís. Ottawa was not listening. So the Metís blocked the arrival of the new lieutenant governor and seized Fort Garry on Nov. 6. Thus began the Red River Rebellion or the First Riel Rebellion. The Metís soon set up a provisional government, the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia, with Riel as president, to handle affairs in the North-West Territory and Rupert’s Land. They established their own newspaper, New Nation.

Legislative Building Grounds, Winnipeg.

After several months of negotiation with Ottawa and much internal wrangling, an agreement was reached allowing the Manitoba Act to be passed, bringing that province into the Canadian Confederation. The provisional government had arrested people who resisted its authority and executed one of them, Thomas Scott. The killing meant there would be no amnesty for leadrs of the provisional government. When military force was sent from Canada to enforce federal law, Riel fled to the United States. The rebellion ended. But a complicated dance took place over the next few years as Riel won election in Manitoba but could not take his seat in parliament for lack of amnesty.

Ultimately, in 1875, he was given amnesty but only if he agreed to remain in exile in New York for the next five years. During that time, his already strong religious obsession took such fierce hold of him that he was given to outbursts of irrational behavior and speech that he was finally committed for some time to an asylum.

Meanwhile, the Metís had moved west. With the buffalo herds rapidly dwindling from the U.S. government-backed assault on them as part of its cultural genocide against the Plain Indians, and with Canadian government assistance reduced in violation of treaties, the Metís found themselves forced to take up agriculture but faced the old problems of land titles.

In early 1885, emissaries were sent to Ottawa to work out some arrangement. Instead, more troops of the North-West Mounted Police were sent and rumor had it, wrongly, that still more would come. Once again, a provisional government was established, this time for Saskatchewan and once again led by Riel, now back in Canada and recovered from his mental aberrations.

In March, a militia of the provisional government clashed with mounted police they encountered by accident while on patrol, a battle ensued, and the militia won. The Metís soon were in open rebellion. They were joined by other First Nations. Some hit-and-run battles were won, but Riel chose to concentrate his forces in Batoche, and after a three-day battle it became clear all was lost. Riel surrendered and was incarcerated. After a trial for treason, he was hanged in November 1885.

He remains a popular hero in Quebec and Manitoba.

Killing of White Buffalo Seen As Possible Hate Crime

By Meteor Blades

(Photo by Kathy Old Crow)

As we reported previously, Lightning Medicine Cloud, the all-white yearling buffalo, was slain and skinned April 30 on the Texas ranch where he was born in a thunderstorm. Because of the sacredness in which white buffalo are held by Lakota and other Plains tribes, a $45,000 reward has been offered for information leading to the conviction of his killer.

Said rancher Arby Little Soldier (Three Affiliated Tribes-Fort Berthold): “Local people here are pushing for this to be considered a hate crime. They’re contacting their senators, their congressmen. There is no penalty for killing a buffalo in the state of Texas. If you kill a horse, you get hung. If you kill a buffalo, nothing happens. So some people around here would like to see this classified as a hate crime, which would make it a federal crime.” Investigators say they have no suspects so far.

Meanwhile, Cynthia Hart-Button, president of the Sacred World Peace Alliance, has donated a white 7-year-old buffalo bull to Little Soldier from the group’s own herd in Oregon. He is named Chief Hiawatha, and Hart-Button said she is sending him to Texas “to protect not only the buffalo but to protect him (Little Soldier) and his family.”

Hart-Button said her organization doesn’t open its sanctuary up to the public because of safety concerns. “We’ve been threatened, people have offered me millions of dollars for their heads and hides,” she said. “I’ve even been offered money for their meat. These are the rarest animals in the world.”

The peace organization’s bull may not carry the same spiritual significance, as Little Soldier said it was bred to be a white buffalo. But he said he’s grateful and excited for the gift.

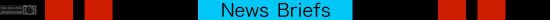

Indians Plan Rally Over Racist Attack on Blind Lakota Man

By Meteor Blades

The American Indian Movement, LastRealIndians.com and Lakota elders and others are planning a rally May 21 in Rapid City, S.D., to protest a racist hate crime. As we reported in the 13th edition of First Nations News & Views, Vernon Traversie (Cheyenne River Sioux) had the letters “KKK” carved or burned into his abdomen while recovering from heart surgery in a Rapid City, S.D., hospital. The 68-year-old is blind. He spent two weeks in recovery at the hospital. During this time, he said, a nurse named “Greg” refused to give him pain medication and otherwise treated him disrespectfully.

When Traversie was discharged, a co-worker, shocked at what she saw, told him he should have photographs taken of his stomach because someone had used a knife or some other means to put three “K’s” on his stomach. That’s the acronym of the racist Ku Klux Klan. Tribal police investigated and took their own photos. They sent copies to Rapid City police. They investigated but filed no charges. FBI agents told Traversie they were going to take a statement from him, but Traversie says he hasn’t heard from the bureau in months.

Traversie said he plans to file a lawsuit.

Harry Smiskin, the chairman of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation wrote a scathing letter regarding the incident. It reads, in part:

As a former tribal and Bureau of Indian Affairs police officer, I am particularly disturbed by what has not taken place in the aftermath of the assault upon Mr. Traversie. Upon the Yakama Nation’s inquiry of his tribal leaders and other relatives, I understand that there has been a complete failure of any federal, state or local law enforcement agency to take any initiative on the matter – despite that the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Police have determined conclusively that a hate crime has been committed against Mr. Traversie. In particular, the United States seems to ignore the trust responsibility it owes Mr. Traversie as a Sioux Indian. Like the assault itself, this federal and state inaction is grossly unjust. […]

Rapid City Hospital and its medical and convalescent “care providers” seem to have violated Mr. Traversie’s civil rights as an American and his fundamental freedoms as a human being. If everything is as it seems, there could be no clearer case of discriminatory treatment, depravation of the equal protection of law, and violation of human rights than here: “KKK” was somehow etched across Mr. Traversie’s abdomen – literally etched in his own blood – because he is a Sioux Indian. Our Lakota Brother was viciously violated because he cannot see. This simply would not have happened to an Anglo American elder or an affluent patient, or to any non-Indian person with sight.

Based on Mr. Traversie’s account and the corroboration of photographs, it appears that Rapid City Regional Hospital allowed a hate crime and a racially motivated attack to take place, at the hands of its “health care professionals.” It does not take a medical professional to observe that three separate incisions across his abdomen that read “KKK” were not the result of open-heart surgery or post-operative care. […]

Again, I have been told that federal, state and local law enforcement agencies have been formally notified of the attack, but have failed to investigate the crime, obtain a search warrant, or apprehend any suspects. This inaction, too, stands as a clear violation of Mr. Traversie’s federal civil rights and his basic human rights. Were Mr. Traversie an Anglo American, we can be sure that federal and state law enforcement would not have handled the referral from the Cheyenne River Police with such disregard.

We urge the United States Department of Justice and the South Dakota U.S. Attorney’s Office to immediately cause an investigation of this hate crime. Anything less would be a violation of the trust responsibility that the United States owes to Mr. Traversie.

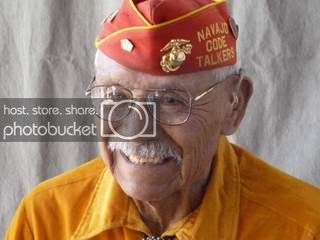

Samuel Tso, VP of the Navajo Code Talkers Association Has Walked On

By navajo

Photo Courtesy of the Navajo Nation

Samuel Tso, 89, of Lukachukai, Ariz. died at San Juan Regional Medical Center in Farmington, N.M. on May 9th after battling cancer.

Tso was Vice President of the Navajo Code Talkers Association whose president, Keith Little died this past January at the age of 87.

Navajo Nation President Ben Shelley said, “The Navajo Nation has lost another Code Talker and that saddens my heart. The Code Talkers have brought great pride to our Nation and the loss of Samuel Tso saddens not only myself, his loss saddens the Navajo Nation. On behalf of the First Lady, the Vice President, and the Navajo people, we offer our prayers, condolences and words of encouragement to the Tso family. Samuel Tso was a true Navajo warrior.”

The Navajo Nation flag was flown at half staff from May 10th through May 14th to honor the Code Talker for his service to the Navajo Nation and his country in World War II.

Tso enlisted in the Marine Corps at age 17 by claiming to be 21 years old. He was sent to Camp Pendleton where he mastered the second version of the code as the original 29 code talkers were being deployed. Tso had to learn both versions.

Tso was of the Zuni Tachii’nii clan and born for the Naakai Dine’e clan on June 22, 1922, at Black Mountain near Many Farms, Ariz. The Navajo introduce themselves first by naming their mother’s clan, since they’re a matrilineal society, and then they say they are born for their father’s clan.

See our previous coverage of Code Talker history here.

U. of Minnesota Students Produce Film Calling for Apology to Dakota Indians

By Meteor Blades

For a dozen years, Carter Meland has taught American Indian literature in the University of Minnesota’s American Indian Studies program. This term 60 students in his “American Indians in Minnesota” class explored an issue we too have examined in FNN&V here and here: the 1862 Dakota War. They came away so appalled that they made a video.

The Dakotas (also known as Santee Sioux or Eastern Dakota) had been promised 1.4 million acres in perpetuity in exchange for giving up 23 million acres. Cut off from their hunting grounds, faced with two bad harvests, encroached on all sides by white settlers and having their treaty-guaranteed food distributions delayed, they sought confirmation of the land deal. They also asked for a loan so they could buy food to hold them over to the next season. The government-appointed Indian agent, Andrew Myrick, said, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.” Five days later, the long-standing tensions exploded and white settlers were attacked. Myrick was soon found dead, his mouth stuff with grass.

President Lincoln’s advisors and the president himself thought perhaps this uprising was engineered by the Confederacy, speculation which was found to be false later. Lincoln at one point contemplated sending 10,000 Rebel prisoners of war under Union command to “Attend to the Indians.” Congress set a $25 bounty for each scalp of an Indian killed in the state. More than 1600 Dakota were placed in a concentration camp where hundreds starved. When the conflict was over, an estimated 500 whites and more than a 1000 Dakota were dead, although the actual numbers will be forever unknown. Several months after the six-week the conflict ended, 38 Dakota were executed on Lincoln’s orders in the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

That, however, was not the end of the maltreatment the state dealt to the Dakota and Ojibwe. A good portion of this was delivered in the cultural genocide that was the mission of the residential boarding schools which many Indian children were forced into after being grabbed from their parents.

When the UofM students were done with their exploration of this history, they decided that a government apology to the Dakota and Ojibwe people was in order. To make their case, they put together a five-part, one-hour video, An Overdue Apology,offering a brief history of those people and their interactions with non-Indians and the U.S. and state governments.

Video will not embed, Part 1 here:

http://www.youtube.com/embed/f…

As you can see, it is an amateur film, created by non-historians, and it suffers from the speed with which it had to be produced. As the Minnesota Post‘s Paul Udstrand writes, “it’s not as polished as a Robert Redford documentary.” But it covers the ground and provides the kind of information that ought to be taught about local tribes in every middle school, high school and college across the nation.

As Udstrand says:

The demand for an apology is quite provocative, but it shouldn’t be. In many ways it’s simply a request that history be recognized and accounted for. Nevertheless many people seem to take reflexive offense at the proposal, as if it’s a personal attack of some kind. This is a request for an apology from the US government and Government of MN, not a request for a personal apology from people who obviously did not participate in historical crimes or injustices. A president or governor may be the voice of that apology, but no one is claiming that they are personally responsible. This is not a bizarre concept, Government[s] are durable entities that are accountable for the duration of their existence. […]

Before you declare an apology to be “meaningless” you need give those requesting the apology a chance to explain what it means to them. And since any consequences of an apology are created by the apology, one cannot declare an apology that has not been rendered to be inconsequential. Obviously an apology could be a meaningless gesture, but it could also be a bridge to a better understanding of history and more respectful relationships among people. You may be able to argue that an apology is useless as long as it’s theoretical, but once an actual apology is issued, it may well create a powerful significance.

Part 2: The Dakota War’s atrocities, Dakota and Ojibwe traditions and daily life.

Part 3: Land allotment, blood quantum issues, the boarding schools and renaming of Indian children with Christian names.

Part 4: Economic revitalization, Indian gaming, interviews with UofM students on their knowledge of the tribes.

Part 5 : Gaining justice, the rationale behind an apology, nine UofM students from Meland’s class express support for Minnesota Indians by giving their own apologies for the injustices that have occurred in the state:

“The fight for indigenous rights fits into a larger struggle for social justice. Social justice is the upholding of the natural law that all persons irrespective of ethnic origin, gender, possessions, race, religion, etc. are to be treated with equity and without prejudice. The path to justice for American Indians in Minnesota starts with recognizing the implications that these historical events have on relations between Native and non-Native communities. Things like the Dakota War and the dispossession of White Earth are part of a colonialist system that damages Native sovereignty and identity.”

An apology isn’t the end-all, be-all of reconciliation. But it’s always a good start.

• Lakota Farmers Reluctantly Join Loggers In Beetle-Infested Forest: The last thing Joe Shark (Oglala-Lakota) wants to be doing is cutting down trees in the forests of the Black Hills sacred to the Lakota. In fact, he has been opposed to logging there for a long time. But the Pine Beetle has killed many trees throughout the West, and the Black Hills are no exception. Left uncut, the infested trees provide an incubator for another generation of the destructive pests. So now Shark and other Oglalas have joined the Lakota Logging Project to cut the infested trees as a means of rescuing the still-healthy ones. Dave Ventimiglia, who co-founded the Lakota Logging Project, said he hopes to eventually raise $150,000 to build a saw mill on the Pine Ridge reservation. Oglala loggers could take the downed trees there and perhaps replace the run-down mobile homes occupied by so many of the tribe.

-Meteor Blades

• Government Cannot Satisfy Indian Need for Eagle Feathers : Officials at the National Eagle Repository in Denver say they cannot keep up with the demand for carcasses needed by American Indians for bald and golden eagle carcasses used in ceremonies. The repository is the only place Indians can legally obtain the carcasses because the birds are heavily protected and their killing outlawed. Nobody can keep eagle feathers or other parts of the birds without a federal permit.

-Meteor Blades

• Federally Recognized Tribes Worry About State-Recognized Tribes: Kerry Holton, president of the Delaware Nation (aka Western Delaware) based in Anardarko, Okla., fears that state recognition of tribes could hurt tribes that are only recognized by the federal government. About half the states, mostly east of the Mississippi, give recognition to tribes based on widely varying rules. At an Indian business group luncheon recently, Holton said of federal aid to the tribes from Washington: “They’re taking some of our pie. That’s our money.” The problem, he said, is that “nobody has defined what that means, to be state-recognized. There are 800 to 1,000 unrecognized entities out there,” he said. He noted that the Lumbee, a state-recognized tribe in North Carolina, recently got $13 million through an Indian Housing Block Grant. The Western Delawares, on the other hand, only received $87,051 for that purpose. The Lumbee population is 55,000; the Western Delawares have 1440 enrolled members, which means that on a per capita basis the Lumbees got four times what the Delawares received. At the request of U.S. Rep. Dan Boren (D-Okla.), the Government Accountability Office drafted a report on the issue of state-recognized tribes. Boren has seen it, but it hasn’t been released to the public. The Lumbees have protested, saying the GAO report was written from the point of view of opponents to state recognition.

-Meteor Blades

• Independent Film on Native Lacrosse Players Debuts: It took six years to get made, but Crooked Arrows opened in a few theaters this past week and will get a wider audience June 1. It’s the story of a troubled team of Indian lacrosse players whose coach is determined to help them win against a better equipped prep-school team. Finding enough Indians who could also play lacrosse and act was the task of Neal Powless. He is a member of the Eel Clan of the Onondaga Nation and director of Native Student Program at Syracuse University. “I was told if I did this movie I was no longer Neal Powless of the Onondaga Nation,” he said. “I was no longer Neal Powless of Syracuse University. I was on my own.” None of the eight players eventually chosen had ever been in front of a movie camera before. Lacrosse is a tradition of the Haudenosaunee nations (also known as the Iroquois Confederacy), which include the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora nations. The film tells the history of lacrosse as well as a more or less familiar feel-good tale of a team that starts out without a chance and proves itself capable of more than the individuals in it thought possible. Some of the actors talk about the movie here.

-Meteor Blades

• School Committee in Maine Town Dumps ‘Redskin’: After several meetings and extensive community discussion, plus the demands of a state commission, the governing body of the schools in Sanford, Maine, voted May 7 to stop using the racist slur “Redskin” for its high school sports teams. The vote was 4-1. The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission has been working for years to get all schools in the state to replace offensive Indian nicknames, logos and mascots with more neutral team names. As we reported in the 11th edition of First Nations News & Views, only about 40 percent of the faculty, students and staff at the Sanford High School favored getting rid of the “Redskin” name and a logo depicting an Indian wearing a “typical Plains Indian headdress, nothing like the traditional attire of Maine’s Indians. At a public meeting in April, Richard Silliboy, tribal councilor of the local Aroostook Band of Micmacs, said the “R” term is just as insulting as “squaw,” a word that has been removed from all public place names in Maine. Silliboy said he’d taken many insults in his life: “Dirty Indian, stinkin’ Indian, drunken Indian” and a “no-good-for-nothing Indian” and “the only good Indian’s a dead Indian.” Meanwhile, the other Sanford in the news, the one in Florida, continues to use a racist mascot by the name of “Sammy Seminole.”

-Meteor Blades

• Boston-Area Indian Center Asks Elizabeth Warren to Come Visit: The head of the North American Indian Center of Boston has extended an invitation to Senate candidate Elizabeth Warren to come visit the center in Jamaica Plain, an historic urban area of the city where she has made many campaign stops. Warren came under fire two weeks ago after it was revealed she listed herself as Native American in a widely circulated law school directory starting in the 1980s. Also, Harvard Law School and the University of Pennsylvania both listed her as a minority professor. No record exists of her objecting to this claim. The right-wing Boston Herald, Republican Sen. Scott Brown and several conservative political pundits have attacked Warren, who is campaigning for Brown’s seat. The attacks have included racial slurs and stereotypes and displayed profound ignorance about Indians. But the critics’ implications that Warren may have used her Indian heritage to gain a hiring or matriculation advantage over other students have not been borne out by records from several universities she attended or was employed by, including Harvard. A reference to Warren’s great-great-great grandmother being listed on a 19th Century marriage certificate as Cherokee was found by a genealogist. But no copy of the marriage certificate itself has been uncovered. “We’ve never heard from Elizabeth Warren, unfortunately,” said NAICOB Executive Director Joanne Dunn in an interview. “We would like to see her. It would be nice if she reached out to us. She can come on down. We’ll make her some frybread.”

-Meteor Blades

• Is ‘One Drop’ Rule Overruled for Indians? Columnist Clarence Page weighs in on the Elizabeth Warren controversy:

If Warren was claiming Indian ancestry when it worked to her benefit, she was following another American tradition, writes David Treuer, an Ojibwe Indian from northern Minnesota and author of Rez Life: An Indian’s Journey Through Reservation Life.

“An Indian identity has become a commodity,” he recently wrote in the Washington Post, “though not one that is openly traded. It has real value in only a few places; the academy is one of them. And like most commodities, it is largely controlled by the elite.”

-Meteor Blades

You can read our take on the Warren affair in the 13th edition of First Nations News & Views.

• Mother’s Day Native American Powwow Celebrates 21st Year: Mittie Wood started the powwow in Dade City, Fla., when her twin grand-daughters were 5 years old in 1991. She did it to honor the Muscogee (Creek) ancestry her mother had quietly inculcated in her and other young kin since she was a young girl. But when she decided to go public with the powwow in Withlacoochee River Park, her mother, then 78, spoke of her fear that exposure would mean the whole family would be shipped off to Oklahoma. Wood’s great-great grandmother had been one of the 70,000 Indians of several tribes forced at gunpoint to go to what is now Oklahoma on the infamous Trail of Tears in the 1830s. Thousands died on the trip. Eventually, Wood’s mother became comfortable with the powwow, which brings out up to 3000 visitors each year. The park on the river (whose Muscogee name means “crooked river”) includes an authentic replica of a Creek village built years ago specifically for the powwow, as well as an arena where storytelling, demonstrations, drumming and performances are held. “It’s like you’re stepping back in time,” said the powwow’s organizer Sharon Thomas, Wood’s daughter.

-Meteor Blades

• Native Kids Participate in Solar-Powered Drag Race: In Albuquerque last Friday, some American Indian elementary students raced drag cars they built with solar technology. It was the 18th Annual Zia Solar Car Race. The goal, besides having fun, is to prepare kids to be future alternative energy leaders. Students from the Santa Ana, San Felipe, Santo Domingo, Cochiti, Tesuque and Isleta Pueblos participated in the event along with a group from Mesa Elementary School on the Navajo Nation.

-Meteor Blades

• Eco-Advocates, Tribes and Others Fight Wind Project: A coalition of environmentalists, tribal representatives, recreational vehicle users, hunters and community residents are calling for a national moratorium on the “fast-tracking” of large energy projects on federal lands. The coalition’s action was kindled by local approval of the Ocotillo Wind Energy Facility, a massive project that will cover 12,500 acres of desert in Imperial County, Calif. In a press release, Terry Weiner, Imperial County Projects Coordinator for the Desert Protective Council, said: “This industrial wind project is symbolic of what’s wrong with the current federal fast-tracking process. We are the canaries in the coal mine. If this is not stopped here, destruction of millions of acres of public lands across the Southwest will likely soon follow.” Unless blocked, the project on Bureau of Land Management land will be going forward under new executive-ordered rules that open up previously protected lands. It will consist of 112 wind turbines-each perched atop a 450-foot-high pillar-with a total generating capacity of 465 megawatts, the 12th largest wind farm in the United States, enough to power 140,000 homes.

In a letter to President Obama in February, Anthony Pico, chairman of the Viejas

band of Kumeyaay Indians, wrote: “We believe that the Department of the Interior is poised to violate the law and our rights to religious freedom and our cultural identities guaranteed by DOI’s own policies, the United States Constitution, and international declarations. We need your help.”

-Meteor Blades

• Smuggled Cultural Items Returned to Tribes: Sixteen Native items a smuggler was caught trying to sneak across the Canadian border into Montana have been returned to the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes at Fort Peck. Eight other items have been returned to other tribes in Montana and one in North Dakota. The items, which include a knife in a beaded sheath, date to the 19th and early 20th centuries. Four of them have distinct Nakoda and Dakota designs; the origins of the rest are less certain. Fort Peck Tribal Cultural Resources Director Curly Youpee (Pabaksa-Dakota and Minicoujou/Hunkpapa-Lakota) said: “These will help with the identification of our own culture for future generations. That’s what we lack, an identity for our children. They need something to grasp onto that’s bigger than them. These are not artifacts. They are cultural items to us, and we need to maintain that.”

-Meteor Blades

Indians have often been referred to as the “Vanishing Americans.” But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither navajo nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

Leave a Reply