After 1871, the United States’ policies regarding American Indian nations was no longer based on negotiating treaties, but on concentrating Indians onto reservations where they could be “civilized” by forcing them to become English-speaking Christian farmers. In his annual report to Congress in 1872, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis A. Walker wrote:

“There is no question of national dignity, be it remembered, involved in the treatment of savages by a civilized power. With wild men, as with wild beasts, the question whether in a given situation one shall fight, coax, or run, is a question merely of what is easiest and safest.”

On the Southern Plains, American policy regarding the so-called “nomadic” tribes, was to destroy the buffalo herds on which they had traditionally depended for subsistence. Once the buffalo had vanished, these tribes would be forced to remain on the reservations or starve. On the other hand, they also starved on the reservations when the supplies which had been promised them as payment for their land failed to arrive.

With regard to the Comanche and Kiowa in Oklahoma, Indian Commissioner Francis A. Walker reported:

“The United States have (sic) given them a noble reservation, and have provided amply for all their wants.”

The Comanche, however, felt that the United States had not “given” them a reservation: they felt that the United States had only recognized their claim to a small portion of their traditional territory.

To pressure the Indians to stay on the reservations, the United States waged an active war against the buffalo. By 1873, non-Indian buffalo hunters (known as “runners”) were crossing into Comanche territory to hunt and the army did nothing to stop them. Instead, the army took a proactive role by providing protection for the runners and by supplying them with both equipment and ammunition.

In 1874, the Comanche held a Sun Dance. This is not a traditional Comanche ceremony, but was borrowed from the Cheyenne. This Sun Dance coincided with the emergence of a new medicine man: Eschiti (Coyote Droppings; also spelled Esa-tai). Unlike most Comanche medicine men, he did not wear a buffalo skull cap or ceremonial mask. He was attired only in breechclout and moccasins. He wore a wide sash of red cloth around his waist. A red-tipped hawk feather was in his hair and from each ear hung a snake rattle.

Eschiti had been given strong powers in a vision quest. In his vision, Eschiti ascended to the home of the Great Spirit, a place which is far above the Christian Heaven. It was reported that Eschiti was capable of vomiting up all the cartridges which might be needed for any gun; that he could raise the dead; that he was bulletproof and could make others bulletproof; that he could control the weather. His messianic message to the people was that he had been sent by the Great Spirit to deliver them from oppression.

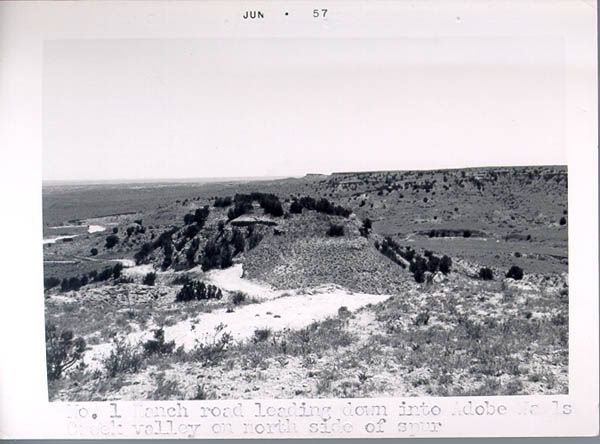

In 1874, in the panhandle of Texas, buffalo hunters armed with high powered telescopic rifles capable of killing buffalo at 600 yards, set up camp at the abandoned trading post of Adobe Walls. The camp was attacked by an intertribal war party of about 300 made up of Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Arapaho warriors. War party leaders included Tabananaka, Wild Horse, Mowaway, Black Beard, and a rising new leader, Quanah. The Indians were confident that Eschiti’s power would render the hunters’ guns useless.

Eschiti had warned the warriors not to kill a skunk on their way to Adobe Walls. His medicine had foreseen that the hunters would be asleep when attacked; they would not use their big guns, and his anti-bullet protection would never be put to the test.

Just as the war party prepared to attack the sleeping buffalo hunters, there was a loud crack which awakened them. The hunters, fearing that the ridge pole had snapped, were suddenly awake and scrambling around.

The hunters settled down for the siege, and with plenty of ammunition and good marksmanship, they repelled the war party. Eschiti blamed the failure of his medicine on the actions of a Cheynne member of the war party who had killed a skunk. Since skunk meat was a favorite of many of the southern plains Indians, killing a skunk was not unusual. Hungry members of a large war party would eat whatever strayed into their path.

One of those who was wounded in the battle was Quanah Parker. After his horse was shot out from under him, he crawled to a buffalo carcass for protection and was shot in the side. He then crawled to a thicket where he remained until another warrior rescued him.

This was the second battle of Adobe Walls-the first battle of Adobe Walls had taken place in 1864 when American troops under Colonel Kit Carson fought against Comanche and Kiowa warriors. The second battle of Adobe Walls marked the beginning of an Indian war known as the Red River War or the Buffalo War.

Army troops were called in to capture the war party, but their movement was hampered by drought and by temperatures well over 100 degrees. Eschiti took credit for arranging the weather. The troops, however, were relentless and managed to destroy lodges and capture horses.

In the battle of Palo Duro Canyon, an American force of 700 was attacked by 75 Cheyenne warriors. The Indians were driven back to a steep wall of the canyon where the full force of about 500 warriors made their stand. The army had superior firepower, including Gatling guns and artillery. The Army troops at this time were armed with .45-caliber single-shot Springfield rifles. Many of the Indians had repeating rifles, such as the 16-shot, lever-action Henry and the .50-caliber Spencer. While the Spencers could fire more rounds in less time than the Springfields, the single-shot army rifles could reach farther across the plains to keep the enemy at bay. It may well have been the better weapon for its time and place.

The Indian warriors under the command of Iron Shirt (Cheyenne), Poor Buffalo (Comanche), and Lone Wolf (Kiowa) were scattered by the superior firepower of the Americans. There were few Indian casualties (it is estimated that only 25 Indians were killed), but the Americans killed more than 1,000 horses and destroyed the Indians’ winter food supply.

This was the last major conflict fought by the Indians of the Southern Plains. It was a last desperate and hopeless resistance to the new order which the United States was to impose upon them.

Leave a Reply