While Grizzly bears were once found throughout much of the American West, today there are two primary locations where Grizzly bears are abundant: Glacier National Park and Yellowstone National Park. Although at one time there were an estimated 50,000 Grizzly bears in North America, the current population is estimated at about 1,800. At the present time, federal wildlife officials are considering lifting protections for the Grizzly bears in the Yellowstone National Park area. This would allow trophy hunting of Grizzly bears outside of the Park. A number of American Indian tribes are protesting this possible decision, citing the spiritual importance of Grizzly bears to traditional Native religions. For many American Indians, the Grizzly bear is a sacred animal.

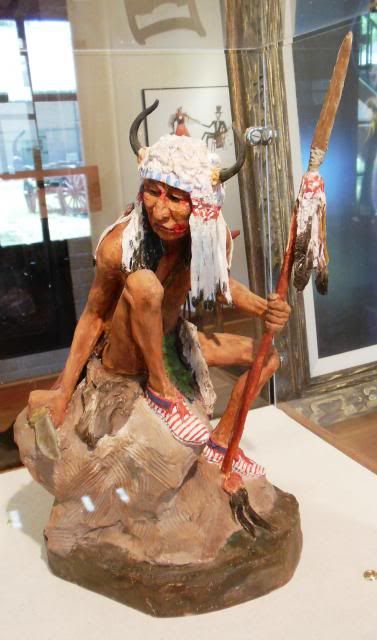

Indians and Bears:

In general, American Indian people have seen themselves as being in harmony with nature and animals, such as the bears, are spoken of not only as people, but as relatives. Some examples of the importance of bears to Native American spirituality are described below.

Among the Ute, the veneration of the bear is expressed ceremonially. Anthropologist Bertha Dutton, in her book The Ranchería, Ute, and Southern Paiute Peoples: Indians of the American Southwest, reports:

“The bear is regarded as the wisest of animals and the bravest of all except the mountain lion; he is thought to possess wonderful magic power. Feeling that the bears are fully aware of the relationship existing between themselves and the Ute, their ceremony of the bear dance assists in strengthening this friendship.”

The Bear Dance is a traditional Ute ceremony which is performed in the Spring. During the 10-day ceremony, a group of men play musical rasps (notched and un-notched sticks) to charm the dancers and propitiate bears. According to oral tradition, this dance was given to the Ute by a bear. The circular dance area represents a bear cave with an opening to the south or southeast. Traditionally, the dance area was enclosed with timbers and pine boughs to a height of about seven feet.

In the Ute Bear Dance, women choose male partners and the women lead in the dancing. Spiritual leader Eddie Box, quoted in Nancy Wood’s book When Buffalo Free the Mountains: The Survival of America’s Ute Indians. says:

“Bear Dance is a rebirth, an awakening of the spirit. It’s a time of awareness. You come to learn from the past in order to arrive at the present with an understanding of the harmony of things.”

Historian Richard Young, in his book The Ute Indians of Colorado in the Twentieth Century, describes the Bear Dance this way:

“Probably the oldest of the Ute Dances, the Bear Dance was a festive, social dance that had always been held in the spring before winter camps disbanded and family groups went their separate ways in search of food.”

The Utes are not the only tribe with a bear dance: the Shoshone, who are linguistically related to the Ute, also have a bear dance. This was originally a hunting dance, which had nothing to do with hunting bears. Men and women would face each other in two long lines and dance in a back-and-forth manner. In one form of the dance, a drum is used while in another form an upside-down basket is scraped by a rasp stick.

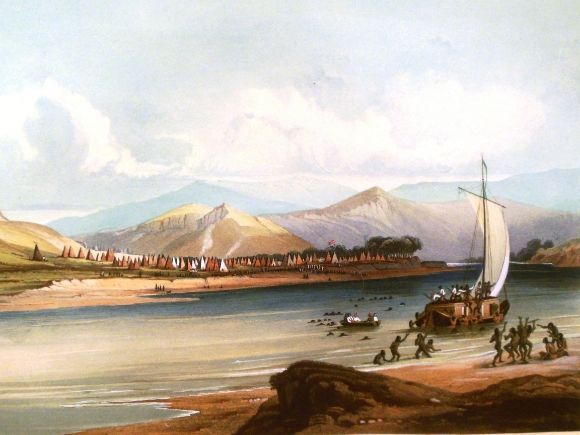

In the Dakotas, the Arikara, an agricultural nation with villages along the Missouri River, also had a bear ceremony. Among the Arikara, the bear-medicine men would put on a ceremony to gain the bear’s help in hunting. The ceremony was conducted in an earth lodge where seven elders would sing a number of songs. A young man would then be instructed to go out and get a certain kind of clay. From this clay, the bear-medicine men would make little figures of men, horses, and buffalo. They would then have the little men hunt and finally have them jump into the fire.

The bear also has important spiritual significance for many other Indians.

Non-Indians and Bears:

When the English began their invasion of North America, they tended to view the Americas as a wilderness, a frightening concept with strong religious overtones. Edwin Churchill, the chief curator at the Maine Museum, writes in his chapter in American Beginnings: Exploration, Culture, and Cartography in the Land of Norumbega:

“They viewed the wilderness as a place where a person might lapse into disordered, confused, or ‘wild conditions’ and then succumb to the animal appetites latent in all men and restrained only by society.”

The English world-view tended to reflect the ethnocentric notion that they were divinely commanded to subdue the earth. According to Frank Waters, in his book Brave are My People: Indian Heroes Not Forgotten:

“They leveled whole forests under the axe, plowed under the grasslands, dammed and drained the rivers, gutted the mountains for gold and silver, and divided and sold the land itself. Accompanying all this destruction was the extermination of birds and beasts, not alone for profit or sport, but to indulge in a wanton lust for killing.”

For the English, taming the wilderness and claiming their dominion over the land involved the eradication of many predators, such as wolves, bears, and (in their minds) Indians. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Americans continued the policy of extermination. Even within national parks, government hunters sought to kill as many wolves and bears as possible.

With regard to Grizzly bears, the extermination policy was nearly successful. One display sign in the Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center in West Yellowstone, Montana indicates:

“Although the Grizzly inspires fear and can pose real danger to people, human beings are powerful natural enemies of this bear. Through killing this animal and competing for the use of its habitat, humans have eliminated the Grizzly from most of its original range.”

The Current Situation:

Protections for Grizzly bears were imposed in 1975 and since that time the bear population has rebounded. According to one newspaper report:

U.S. wildlife officials and their state counterparts in Montana, Idaho and Wyoming contend the region’s 700 to 1,000 bears are biologically recovered. They’ve been pushing for almost a decade to revoke the animal’s threatened status, a step that was taken in 2007 only to be reversed by a federal judge two years later.

Removing federal protections for Grizzly bears in the Yellowstone region would mean that the animals would be under state management. This would allow the states—Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming—to allow hunting of them. Wildlife officials in these states have been advocating bear hunts as a way to deal with problem bears.

Grizzlies have killed six people in and around Yellowstone National Park since 2010. In addition, they have regularly mauled both domestic livestock and hunters outside of the Park. The ranching industry has lobbied for eliminating protections for the Grizzly bears.

Under the Endangered Species Act, decisions regarding the Grizzly bear should be guided by “best available science,” but federal officials have indicated that they will take tribal views into consideration. Consultation with the tribes is required by Presidential Executive Orders and, according to tribal officials, by treaty obligation. Federal officials report that they have consulted with five tribes and have discussions scheduled with two more. In addition, letters have been sent to more than 50 tribes inviting them to participate in the discussions.

Tribal leaders from several tribes have opposed the removal of Grizzly hunting restrictions. The Fort Hall Reservation in Idaho is the home of the Shoshone and Bannock Tribes. Tribal Vice-Chairman Lee Juan Tyler has stated:

“These are our treaty lands, our ancestral homelands. Too many times in our relationship with the federal government we have surprises. … We want the grizzly bear protected with those lands, and the grizzly bear returned to areas where we can co-manage them.”

Federal officials are expected to rule on lifting protections for the Grizzly bear sometime in the next several months. This decision would impact only the bears in the area around Yellowstone National Park. The area around Glacier National Park would not be impacted by this decision.

Leave a Reply