When cultures are under stress from rapid change, particular change which is forced upon the people from outside agents, there frequently arise cultural and religious movements which attempt to revitalize the culture and resist change. Many of these revitalization movements are short lived, while others go on to become established religions. In some cases, particularly with regard to cultural revitalization movements among American Indian nations, these movements have been suppressed through military actions. One of these happened on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona in 1880.

During the 1870s the U.S. military waged a war against the Apache bands in Arizona and New Mexico. The army also crossed into Mexico to attack the bands. The purpose of the military action was to pacify the Apache and to force the bands to live on small reservations which would be out of the way of American settlers who wanted Apache land. In some cases, military actions against the Apache seemed genocidal in their attempts to exterminate men, women, and children. The war against the Apache was urged on by the media, by the Arizona legislature, and by many civic groups. The Arizona Citizen, for example, called for the slaying of every Apache man, women, and child.

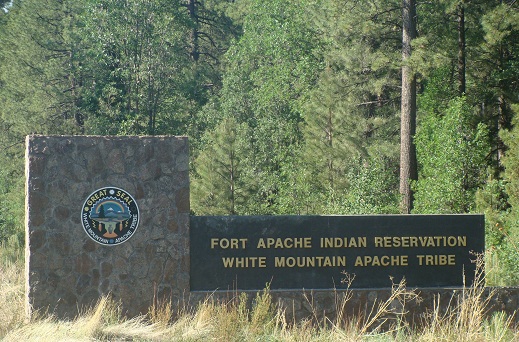

In Arizona, the White Mountain Apache Reservation was formally established by Presidential executive order in 1871. This reservation was to become the home to the Western Apache bands. As with other Indian reservations, lands were removed from the reservation when they were found to contain precious metals which non-Indians wanted to mine.

In 1880 a White Mountain Apache elder, Nakaidoklini, talked to the Apaches about a new religion in which dead warriors would return to help the people drive the Americans from their territory. He taught his followers a new dance in which the dancers are arranged like the spokes on a wheel facing inward.

Nakaidoklini announced that he would bring back two chiefs from the dead if the people gave him enough horses and blankets. When the dead chiefs failed to materialize, Nakaidoklini announced that they had refused to return because of the Americans and they would return when the Americans were gone.

In response to Nakaidoklini’s small religious movement, The United States sent soldiers with orders to arrest him or to kill him or both for his teachings. The soldiers entered his quarters and told the old man that he must come with them. Nakaidoklini quietly submited to arrest. On the return journey, the troops were followed by many Apache. As the Apache moved closer, their faces painted, the officer in charge ordered them back and the shooting broke out. The Apache scouts who had come with the troops, then began firing on the soldiers. The officer ordered Nakaidoklini killed and a soldier shot Nakaidoklini at point blank range.

Following this incident, three of the four Chiricahua bands left the San Carlos Reservation and began a series of raids which resulted in a prolonged campaign by General George Crook to “pacify” the Apaches.

The rebel bands, with 74 men and 300 women, included the Nednhi led by Chief Juh and Geronimo, the Chokonen led by Naiche (the son of Cochise), Chato, and Chihuahua, and the Bedonkohe led by Bonito. The Apache who remained on the reservation, including 250 Chiricahua, generally oppose the breakout.

Three of the scouts who turned on the troops – Sergeant Dandy Jim, Sergeant Dead Shot, and Corporal Skippy – were court-martialed, found guilty of mutiny, and hanged. Several others were sent to Alcatraz.

Leave a Reply