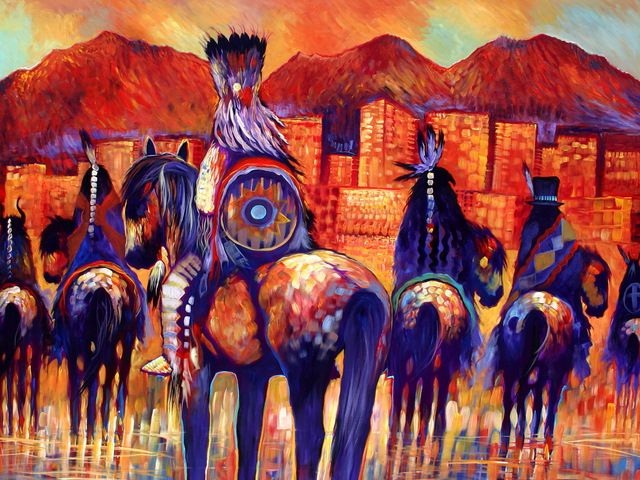

Living in exile in their own land; contemporary Native American artists

Floris Schreve on June 11 2010

English version of the Dutch original, published in Decorum, journal of the department of Art History, University of Leiden, March 1997, issue 1+2 (also published on this blog, see HERE)

‘I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream . . . . the nation’s hope has broken and scattered. There is no centre any longer, and the sacred tree is dead’. [1]

Black Elk

‘While the entire world is in an identity crisis, the New Indian still knows who he is’ [2]

Fritz Scholder

These quotations, the first of the Lakota Black Elk on the massacre of Wounded Knee in 1890 and the second by the artist Fritz Scholder (Luseno) from the early seventies, show the North American Indians in this century have experienced turbulent changes. After the various Indian nations and tribes were subdued and banned to reservations, it was thought that America’s original inhabitants would disappear very soon. Nearly a century later, despite the social and economic problems, the Native Americans found a defined identity in a totally changed world.

The Native Americans manifest themselves also artistic in various ways. In the reservations, which are relatively isolated from the rest of American society, a revival can be observed of the traditional arts. This applies especially to the peoples in the south-western United States (Navaho, Pueblo, Hopi) and for the peoples of the Canadian west coast (Haida, Tlingit, Kwakiutl). Elsewhere in North America there is also a revival of various tribal traditions.

These artistic expressions are not limited to nostalgia. Many of these artists are experimenting with new materials and shapes to the traditional imagery a contemporary face. The most famous artists in this way to work are the ‘sand painter’ Joe Ben Jr. (Navaho) and the goldsmith and sculptor Bill Reid (Haida).

In this context the more recent emerged artistic expressions are central. Beside artists of Native American origin who work in the tradition of their own cultural heritage, since the fifties a new phenomenon emerged, called ‘pan-indianism’, a movement that was close related with the increasing political and emancipatory struggle of the original inhabitants of America. This new activism was mainly originated by Native Americans living outside the reservations, and mostly had received university education.

Although the first and long time the only Indian with a university education, the famous Indian affairs commissioner Donehogawa or Ely Parker, lived in the nineteenth century, the Native Americans in general are still an underclass minority in American society. From the fifties however, there were more Indians who followed an academic education.

They were mainly representatives of this group who reconsider their own identity. Also there were several political organizations established as ‘The National Congress of American Indians’ and militant movements like the ‘American Indian Movement’ (AIM) and ‘Red Power’ and organized political actions which sometimes took the attention of the world press, like the occupations of Alcatraz (1969) and Wounded Knee (1973, see this documentary by Roelof Kiers for the Dutch television). In both cases these were intertribal actions, organized by AIM.

These activities can’t be understood out of context of the general protest movement of the sixties. The rise of the emancipation movement of Native Americans took place at the same time as the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam demonstrations. However, the most important Native American writer of that time, Vine Deloria Jr. (Lakota), president of the ‘National Congress of American Indians’ during the seventies and author of We talk, you listen, God is Red and Custer died for Your Sins, stipulates the differences with the Afro-American emancipation movement. Although he clearly expresses his sympathy for the Civil Rights Movement, in Custer died for your Sins (the title refers to the U.S. General Custer in 1876 with the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the U.S. Army was massacred by the Lakota, the Western or Teton Sioux , led by Sitting Bull at the Little Bighorn) he states that the Native Americans other goals than, say, Afro-Americans. In his view the main aim of the natives is not to integrate into American society, because Western culture is imposed on them involuntarily. In his manifesto Vine Deloria Jr. pleas as much as possible autonomy for the indigenous population, for self determination, land and particularly the maintenance of their own cultural heritage. In this regard he particularly criticizes the romantic attitude of some Westerners to the ‘noble savage’. He rejects a fashionable interest in Indian mysticism in the western world, in his opinion it is outright theft of ideas, from one hypocrisy after first massive genocide was committed on the Native Americans. [3] These ideas are also in line with that of Pam Colorado (Oneida), professor at the University of Toronto: ‘In the end non Indians will have complete power to define what is and what is not Indian, even for Indians … When this happens, the last vestiges of Indian Society and Indian rights will disappear. Non Indians will then ‘own’ our heritage and ideas as thoroughly as they now claim to own our land and resources’.[4]

continue on http://fhs1973.wordpress.com/2…

Leave a Reply