About 17 million years ago, the Colorado River began to create the Grand Canyon. In terms of geology, the Grand Canyon is 277 miles long; it is up to 18 miles wide; and in some places it is more than a mile deep. It first enters European history in 1540 when Spanish explorers with Hopi guides travelled to the South Rim. Since parts of the Grand Canyon are sacred to the Hopi, the Hopi guides did not show the Spanish the trails to the bottom. The Spanish were not the first non-Indians to see the wonders of the Grand Canyon: In 485 CE, a group of Buddhist monks under the leadership of Hwui Shan were shown the Grand Canyon by the Hopi. When they returned to China, they recorded their observations in the state records.

While both the Spanish and the Buddhists left written records, American Indians have known about, visited, and lived in the Grand Canyon for thousands of years. Our evidence of this comes from the archaeological record as well as oral traditions.

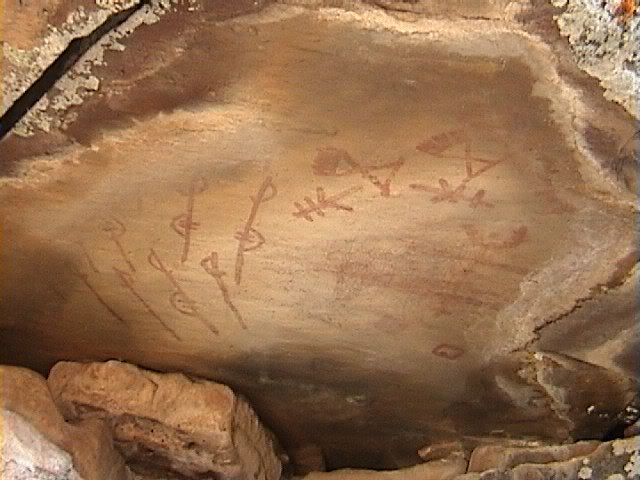

By 5000 BCE, Indian people were creating anthropomorphic rock art images in the White River drainage area. These rock art sites, called the Barrier Canyon Style by archaeologists, served as religious shrines or ceremonial places. They are located in remote places and depict large, shamanistic figures. Many of the figures appear to be ghostly and may represent trance-state experiences. At some sites the rock paintings appear to have been the work of one person or a limited number of people. This suggests that they were probably made by a select few artists or shamans.

Hunting and gathering people, known to archaeologists as the Desert Archaic Peoples, were living in the Grand Canyon by 3000 BCE,

By 2390 BCE, Indian people were creating shrine caves high in the walls of the Grand Canyon. In these caves there were rows of rock cairns. Some of the cairns were made of only piles of rock. Others were made of combinations of rocks and pieces of late Pleistocene packrat midden that had been dug out of larger middens in the cave. Some of the cairns incorporated horn sheaths from the extinct Harrington’s mountain goat as well as split-twig figures. The use of the mountain goat remains suggest that the people considered the mountain goat fossils unusual.

Indian people continued to use the Grand Canyon for spiritual or ceremonial purposes. Archaeologists found that by 2000 BCE, Indian people were placing miniature figures in caves in the walls of the Grand Canyon. The caves were difficult to reach because of the sheer precipices and lack handholds and footholds. These figures were made by bending and folding a single willow twig. Most of these figures are thought to represent deer or bighorn sheep, while others may represent antelope. The figures may have been made for use in hunting medicine. The objects were placed under flat rocks or small cairns, and no accompanying relics have ever been found.

There is evidence that by 700 CE Indian people had established farming on both the North and South rims of the Grand Canyon. With the increase in precipitation in the area about 1000 CE, there was an increase in the number of people who were living in the Grand Canyon. At this time, the Indian farmers were constructing terraced fields for their corn, beans, squash, and cotton. These terraces covered the rich deltas where side canyons meet the Colorado. The Grand Canyon farmers built cliff granaries to hold excess seeds and hunters stalked deer at higher elevations.

At this time (1000 CE) the Havasupai moved from the Coconino Plateau into Cataract Creek Canyon, a side canyon of the Grand Canyon. Their living site on the canyon floor could be reached only by a narrow trail which snaked down from the plateau. Here they began to call themselves “the people of the blue water.” Within 50 years, the Havasupai were cultivating lands on the floor of the Grand Canyon on a permanent basis. This was the beginning of the characteristic Havasupai economic pattern based on summer irrigation agriculture in the canyon and winter hunting-gathering on the plateau.

By 1050 BCE, ancestral Puebloans had communities on the floor of the Grand Canyon near arable deltas and on the rim of the canyon. They would alternate their residences seasonally between these two areas. With a 5,600-foot elevation differential, this gave these farmers the advantage of a long growing season. There were now several hundred pueblos along the base of the canyon.

At this same time, a small, single family dwelling was constructed at Walhalla Glades on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. The Indians at Walhalla Glades probably moved into the inner canyon in winter to avoid the frigid temperatures and deep snows of the North Rim’s eight-thousand-foot elevation.

Within the Grand Canyon, Indian people built a pithouse at Bright Angel (a popular tourist spot today) about 1050 CE. Fifteen years later they abandoned this pithouse. Fifty years later, Indian people built a small pueblo at Bright Angel. They were farming a small garden. This pueblo was occupied for about 90 years.

A major regional drought started in 1225 and as a result, most of the Grand Canyon was deserted with regard to permanent occupation. Indian people continued to use it for ceremonial purposes, and the Havasupai still live there year-round.

Leave a Reply