The Sonoran Desert which stretches across part of the present-day American state of Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora is an area of very hot summers (high temperatures may reach 120° F) and relatively little rain. The Tohono O’odham live in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico. The Tohono O’odham are also called Papago which is derived from the Akimel O’odham name Papahvi-o-tan which means “bean people.” The Tohono O’odham are the descendants of the ancient Hohokam who farmed the desert with irrigated canals more than a thousand years ago.

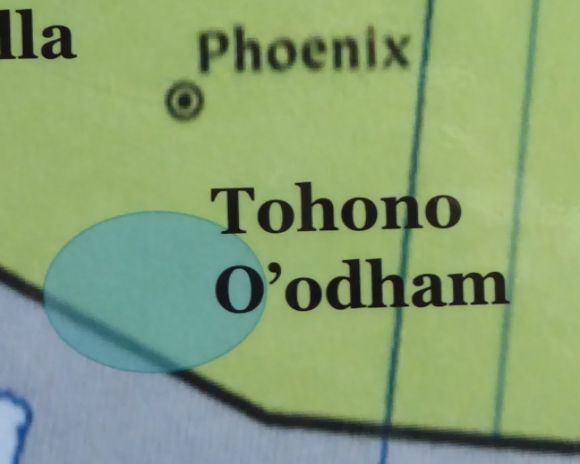

This map shows the location of the Tohono O’odham.

This map shows the location of the Tohono O’odham.

The Spanish called this region the Pimería Alta (the High Pima county). In the central portion of the Pimería Alta there is a bi-seasonal rainfall pattern which allowed for some agriculture. In this area the people – Tohono O’odham – had winter villages in the mountain foothills near permanent water sources and summer villages on the plains where they could farm at the mouths of the washes.

Dwellings were round buildings with brush walls and a dry earth roof. Construction material came from cactuses, trees, shrubs, grasses, and other plants. In addition to dwellings, the villages contained ramadas (roofed, open-sided structures which provided shade), open air kitchens, and storage houses.

In the Tohono O’odham area, most of the yearly rainfall comes in localized thundershowers in July and August. The water from these thundershowers does not sink into the ground but runs off in washes. Tohono O’odham fields were placed at the mouths of the washes where the collected water spreads out. Brush dams and irrigation canals helped bring the water to the fields.

The Tohono O’odham planted their main crops – corn, squash, beans – in July or August. The crops were then harvested in October or November. These crops provided about a fifth of their food.

The Tohono O’odham also raised tobacco (nicotiana attenuata) which was smoked in a cane tube.

Wild plants were an important source of food and these included: mesquite, ironwood, palo verde, amaranth, saltbush, lambs quarter, mustard, horse bean, and squash. They also used acorns and other wild nuts. Over 50 edible plants were used.

Shown above is the Tohono O’odham display at the Riverside (CA) Metropolitan Museum.

Shown above is the Tohono O’odham display at the Riverside (CA) Metropolitan Museum.  Shown above is a diorama depicting Tohono O’odham village life. This small model was constructed in 1901 by the Smithsonian Institution.

Shown above is a diorama depicting Tohono O’odham village life. This small model was constructed in 1901 by the Smithsonian Institution.

According to the Museum display:

“This model of a Tohono O’odham village has several types of structures. Light construction was preferred over more permanent buildings as the people moved frequently. The domed house has a frame made of mesquite poles or other wood covered with brush and tied with cordage made from yucca or agave leaves. The square building is a jacal, which has an upright frame and walls of tied sticks covered with grass and clay or mud. White tepary beans are drying in the sun on this jacal’s roof. Clay pots or ollas used for food and water storage are seen around the open-air kitchen where cooking takes place. Here a woman is using a mano and metate to grind food—she could be making corn meal or mesquite flour.”

Diorama detail showing the cooking area.

Diorama detail showing the cooking area.  Shown above is a wine basket made about 1900. This basket would have been used in fermenting the wine made from Saguaro cactus used in a ceremony to bring rain to the desert.

Shown above is a wine basket made about 1900. This basket would have been used in fermenting the wine made from Saguaro cactus used in a ceremony to bring rain to the desert.

The Saguaro Festival marks the beginning of the rainy season in July. The purpose of the ceremony is to bring rain to the desert. As a part of the ceremony, cactus wine – tiswin – is made and consumed.

The local village representative plus three guests occupy four directional positions representing the rain spirits of these directions. Cup bearers then bring the tiswin. They drink a portion of it and sing four rain songs. They then dip their fingers into the gourd and sprinkle the beverage on the ground to symbolize rainfall. The first night of the festival is called “sit-and-drink” and during this time ritual speeches are made. Following this everyone consumes the tiswin until it is gone. In the words of one woman:

“People must all make themselves drunk like plants in the rain and they must sing for happiness.”

The people also made annual pilgrimages to salt flats near the Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez). Like the Saguaro Festival, the pilgrimage was intended to help bring the rain. Regarding the salt pilgrimage to the Sea of Cortez and the Saguaro Festival, Carl Waldman, in his book Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, writes:

“They believed that the rain spirits lived there, and prayed to them for more of the valuable water. They believed that drinking of saguaro wine in great amounts would help bring rain.”

Shown above is an early twentieth century basket tray which would have been used to serve food.

Shown above is an early twentieth century basket tray which would have been used to serve food.  Shown above is a basketry olla made about 1970. Baskets of this type are made for sale.

Shown above is a basketry olla made about 1970. Baskets of this type are made for sale.  Shown above is a shallow basket bowl made about 1900. This type of basket was used for collecting seeds and for winnowing.

Shown above is a shallow basket bowl made about 1900. This type of basket was used for collecting seeds and for winnowing.  Shown above is a gathering basket (kiahu) made in the late nineteenth century. This type of basket was worn on the back, held by a trump line across the forehead.

Shown above is a gathering basket (kiahu) made in the late nineteenth century. This type of basket was worn on the back, held by a trump line across the forehead.  This photograph shows how the basket is carried.

This photograph shows how the basket is carried.

According to oral traditions, these baskets walked by themselves until Coyote laughed at seeing them in motion. Then they became the women’s burden. Using the burden baskets, Tohono O’odham women would often carry burdens weighing up to 100 pounds.

Shown above are a stone mano and metate made in the nineteenth century.

Shown above are a stone mano and metate made in the nineteenth century.  Shown above are some mesquite bean pods. Dried pods can be ground into flour. The flour can be used for many things, including cookies, tortillas, and soup thickeners. The mesquite bean was important and provided emergency rations at times when other food was scarce.

Shown above are some mesquite bean pods. Dried pods can be ground into flour. The flour can be used for many things, including cookies, tortillas, and soup thickeners. The mesquite bean was important and provided emergency rations at times when other food was scarce.  Shown above is a pottery olla made in the early twentieth century. This olla has become blackened because it was used for cooking on a fire.

Shown above is a pottery olla made in the early twentieth century. This olla has become blackened because it was used for cooking on a fire.

Leave a Reply