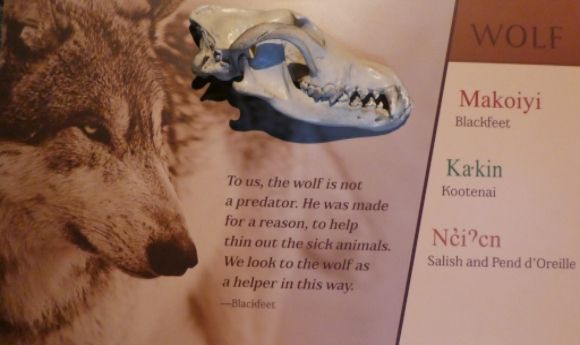

What is now Glacier National Park in Montana was an important resource and spiritual area for the Salish-speaking Pend d’Oreille and Flathead, for the Kootenai, and for the Blackfoot. The visitor center at St. Mary entrance has a small Native American display.

Salish and Pend d’Oreille

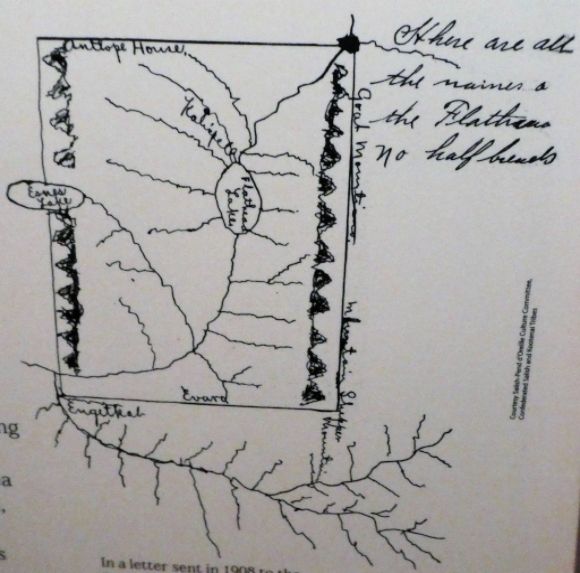

Salish leader Sam Resurrection drew this map of the Flathead Reservation in 1908 in a letter to the Secretary of the Interior. The map shows how tribal leaders at the 1855 Hellgate Treaty Council interpreted their reservation. It encompassed, from their understanding, nearly all of the Flathead drainage system.

According to the display:

“The Salish and Pend d’Oreille draw upon a profound knowledge and understanding of our homeland, and upon a deeply spiritual relationship with plants and animals.”

With regard to Glacier National Park:

“When natural areas start to disappear, cultures will disappear. National parks provide a means for keeping culture alive; they have become sacred places and sanctuaries.

We often conduct field trips with elders to record their knowledge of the land, traditional place names, and of tribal history. For the elders, these trips are often both joyful and sad. These trips record the tribal relationship with these places in Salish and Pend d’Oreille culture, but also their loss.”

Kootenai

According to the display:

“There were basically three ‘periods’ of time in Kootenai history: the spiritual period, the animal period, and the human period, after the creation of people. Inhabitants of the earth were interchangeable and times was not considered to be linear-sequential.

Spirits, animals, and humans coexist and have shared experiences in the history of the earth. There is no hierarchy.”

With regard to Glacier National Park:

“We are thankful for the preservation of an area that has 500-year-old cedar trees who listened to our ancestors sing and dance long before the Kootenai were aware of Europeans. Yet, we are also aware that this place has not been preserved because of its significance to us. It is preserved because of the many visitors that come to the area.”

Blackfoot

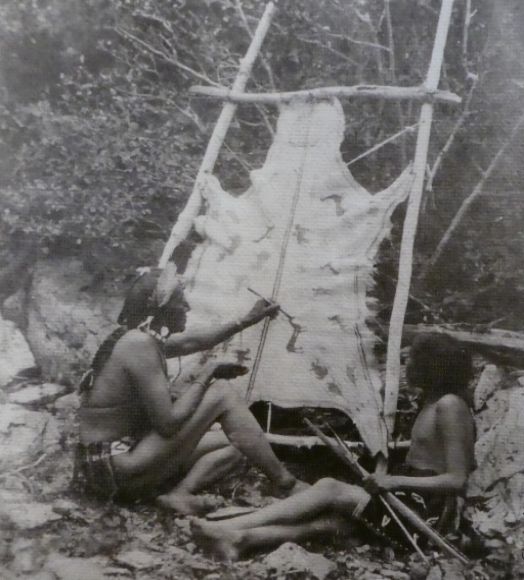

Shown above is Big Spring (Blackfoot) painting on a stretched hide. This photograph was taken before 1925.

According to the display:

“We are Ni-tsi-ta-pi-ksi—this means ‘real people’ and distinguishes us as human beings from the rest of Creation. We share the earth with four-legged animals, plants, rocks, and the earth itself. We call these ksahkomi-tapiksi (Earth Beings).”

Shown above is a map of the 1855 Blackfoot Treaty reservation.

Shown above is a map of the 1855 Blackfoot Treaty reservation.  This map shows the boundary between the Blackfeet Reservation and Glacier National Park showing the contested ceded strip.

This map shows the boundary between the Blackfeet Reservation and Glacier National Park showing the contested ceded strip.

According to the Blackfoot:

“We contest various parts of the 1895 agreement that transferred the ceded strip, the land east of the Continental Divide, to the US government. In 1910, the northern portion of the ceded strip became the eastern part of Glacier National Park.”

With regard to Glacier National Park:

“The landscape of Glacier is the source of our oldest and most venerated ceremony, the Beaver Bundle. The inception of the national park concept preserved the landscape, but excluded Blackfeet cultural and spiritual practices. The Blackfeet still retain hope to use the park area, maybe through future cooperative agreements.”

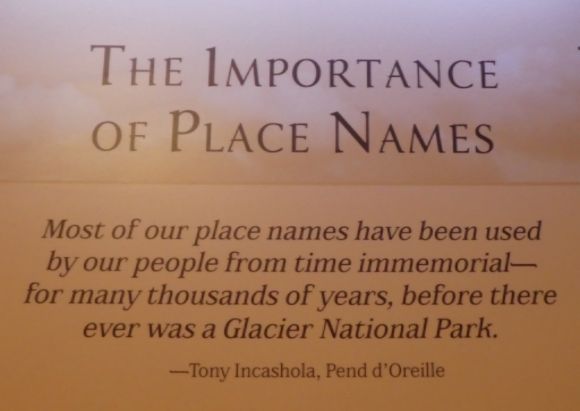

Place Names

Place names forge communities, generate myths, affirm relationships, and establish claims. In his book Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America, Felipe Fernández-Armesto writes:

“Naming is often said to be a kind of magic. Names change natures. They forge communities. They generate myths. They affirm relationships. They establish claims, especially of parentage and proprietorship. They affect perceptions of things named. They attract and repel. They are hard to get rid of. Their effects are almost indelible. They influence behavior, as people try to live up to them.”

Place names—technically known as toponyms—are long-lasting and may endure long after the people who gave the name have vanished from the landscape. Place names can, therefore, provide additional historical and linguistic background for many regions and countries. In Glacier National Park, there are relatively few Native American place names which appear on tourist maps.

Salish and Pend d’Oreille:

“The ancient spiritual and material importance of the area to the tribes is reflected in its many Salish-language place names, a number of which are still known.”

Kootenai:

“A place is usually named for a significant event that happened there or for a person or family that lived in the area. This means that a river or stream may not have the same name its whole length from glacier to ocean.”

Blackfeet:

“Mountains are significant to us because they provide knowledge. Mountains have a future value to us; we don’t know what will be revealed in the future.”

Leave a Reply