The area between the Cascade Mountains and the Rocky Mountains in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, British Columbia, and Western Montana is known as the Plateau Culture area. From north to south it runs from the Fraser River in the north to the Blue Mountains in the south. Much of the area is classified as semi-arid. Part of it is mountainous with pine forests in the higher elevations.

Most of the Indian tribes of this area have linguistic and historic ties to the tribes of the Northwest Coast. In many respects, the Plateau cultures represent an inland extension of the coastal cultures. Villages, usually occupied for 7-8 months each year, were established along rivers, most frequently at the conjunction of tributary water ways where fish were abundant. Canoes, prior to the introduction of the horse, were an important means of travel.

For the indigenous people of the Columbia Plateau, plants were an important food source. In her essay in Woven History: Native American Basketry, Mary Dodds Schlick (2004: 10) reports:

“For uncounted centuries, the plants that grow in the rocky hillsides of the Columbia Plateau provided more than half of the calories for the Native people living here. Each spring the families moved across the hillsides digging bitterroot, camas, wild carrot, and other foods, putting them into these soft bags tied at their waists. The roots were skinned, dried in the sun, and stored for winter in flat, root storage bags.”

The Plateau tribes made a wide variety of different kinds of baskets, including round twined bags for gathering roots and for storing dried salmon; large flat bags for storing dried foods; coiled baskets for gathering berries and for cooking; and folded cedar bark baskets which could be quickly made as needed. Baskets were often a trade item, particularly after the reservation era. Mary Dodds Schlick writes:

“The Native people of the Columbia Plateau are rich in basketmaking tradition. For thousands of years their ancestors have used the roots, bark and grasses of the region to fashion containers for all their needs. Today a small number of descendants of these basketmakers continue this ancient heritage, an art form known worldwide for fine craftsmanship, variety in design, and beauty.”

In their entry on basketry in the Handbook of North American Indians, Richard Conn and Mary Dodds Schlick write:

“Basketry is surely one of the most significant, and least appreciated, creative and technological achievements of the world’s peoples. Unlike the more-esteemed potters or beadworkers, basketmakers must create the basic form while simultaneously planning and placing the decoration correctly.”

The oldest form of the Plateau bags was woven using Indian hemp (Apocynum cannadbinum). In an article in American Indian Art David Fraser reports:

“With the coming of Europeans, Native weavers began using commercial jute and cotton yarn as warps, cotton and linen as wefts, and cornhusk and wool as false embroidery material, dyed as necessary to create color patterning.”

In her book Columbia River Basketry: Gift of the Ancestors, Gift of the Earth, Mary Dodds Schlick reports:

“Most basketmaking, that essential industry, was carried out in wintertime when food-gathering was over for the year and families could settle into their winter homes.”

Most of the basketmakers were women, but many young boys also learned this skill. Today, there are a number of men who have continued this traditional craft.

The Portland Art Museum has several displays of Plateau Indian basketry.

Tribes

The Portland Art Museum display reflects the work of weavers, both historic and modern, from several Plateau tribes:

The Wasco, who are currently on the Warm Springs Reservation, received their name from the village of Wasq’u, their principal village. The name means “small bowl” or “cup” and refers to a cup-shaped rock near the village into which a spring bubbled. The Wasco traditionally lived on the south bank of the Columbia River between The Dalles and Hood River. The Wishram were neighbors of the Wasco and the two groups shared many cultural traits. Josephine Paterek, in her book Encyclopedia of American Indian Costume, reports:

“Both the Wasco and the Wishram developed a remarkable art style, readily seen in the fine baskets and bags they wove decorated in shades of brown on natural cream-colored fibers (usually apocynum).”

The Penutian-speaking Yakama lived along the Yakima River, a tributary of the Columbia River. Their names means “runaway.”

The Colville today are a confederation of about ten tribes on the Colville Reservation in Washington. These tribes include Chelan, Colville, Entiat, Lakes, Methow, Moses-Columbia, Palus, Sanpoil-Nespelem, Southern Okanogan, and Wenatchi. The Sanpoil and Nespelem lived on the Columbia River above the Big Bend and, while distinct tribes, they were so closely associated that outsiders considered them to be one people.

The Nimipu were given the designation Nez Perce (“pierced noses”) by the French fur traders. Their homeland was in the area of the Snake and Salmon Rivers which are tributaries of the Columbia River. It should be noted that the Nez Perce did not pierce their noses.

The Klikitat are one of the tribes on the Yakama Reservation.

The Baskets

Shown above is a cornhusk bag which was made about 1900. In the nineteenth century, fur traders and missionaries brought in corn as a food crop. Native weavers began using the softer corn husks instead of native grass as a decorative element. These bags then became known as cornhusk bags.

Shown above is a cornhusk bag which was made about 1900. In the nineteenth century, fur traders and missionaries brought in corn as a food crop. Native weavers began using the softer corn husks instead of native grass as a decorative element. These bags then became known as cornhusk bags.  Shown above is a bandolier bag made in 1997 by Darryl Lopez (Wasco/Nez Perce).

Shown above is a bandolier bag made in 1997 by Darryl Lopez (Wasco/Nez Perce).  Shown above is a beaded bag made about 1890 by Ellen Underwood (Wasco).

Shown above is a beaded bag made about 1890 by Ellen Underwood (Wasco).  Shown above is a beaded bag made in 1997 by Sophie George (Yakama/Colville).

Shown above is a beaded bag made in 1997 by Sophie George (Yakama/Colville).  Shown above is a Nez Perce flat bag made about 1900.

Shown above is a Nez Perce flat bag made about 1900.  Shown above is a cylinder bag made by Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco) in 1999.

Shown above is a cylinder bag made by Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco) in 1999.

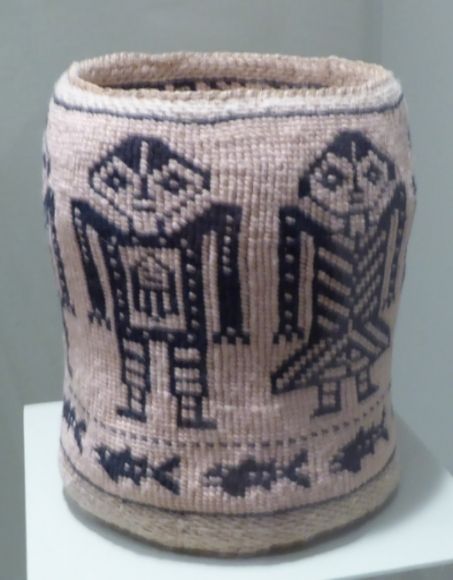

Shown above is a Wasco cylinder bag made about 1920.

Shown above is a Wasco cylinder bag made about 1920.

Shown above is a cylinder bag made about 1890.

Shown above is a cylinder bag made about 1890.  Shown above is a Wasco cylinder bag made about 1890.

Shown above is a Wasco cylinder bag made about 1890.

Shown above is a Wasco cylinder bag made about 1890.

Shown above is a Wasco cylinder bag made about 1890.

Shown above is Red Roll Call made by Joe Feddersen (Colville) made in 2010.

Shown above is Red Roll Call made by Joe Feddersen (Colville) made in 2010.

Shown above are some woven Plateau women’s hats: Klamath (1900), Nez Perce (1890), Karuk (1900), and unidentified Plateau (1900/1920).

Shown above are some woven Plateau women’s hats: Klamath (1900), Nez Perce (1890), Karuk (1900), and unidentified Plateau (1900/1920).

One of the distinctive characteristics of women’s clothing among the Plateau tribes is the basket hat. This hat is usually described as being fez-shaped with designs woven into it. In her book Columbia River Basketry: Gift of the Ancestors, Gift of the Earth, Mary Dodds Schlick reports:

“The graceful proportions of these hats and the varied execution of the traditional banded zigzag design required great skill on the part of the weaver.”

Richard Conn and Mary Dodds Schlick report:

“Most basket hats were made in the southern Plateau by the people who were settled on the Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Yakima reservations and by the Joseph band of Nez Perce living on the Colville Reservation.”

Shown above is a Klickitat gathering basket with tump line made about 1900.

Shown above is a Klickitat gathering basket with tump line made about 1900.  Shown above is a Cowlitz basket made about 1900.

Shown above is a Cowlitz basket made about 1900.

Shown above is a Clatsop clam basket. Notice the open weave which allows water to drain off.

Shown above is a Clatsop clam basket. Notice the open weave which allows water to drain off.

Shown above is Hanis Coos bag made by Sara Siestreem in 2015.

Shown above is Hanis Coos bag made by Sara Siestreem in 2015.

Leave a Reply