The Pueblos are the village agriculturists of New Mexico and Northern Arizona. While the Pueblos are usually lumped together in both the anthropological and historical writings as though they are a single cultural group, they are linguistically and culturally divergent. The Pueblos speak six mutually unintelligible languages and occupy more than 30 villages in a rough crescent more than 400 miles in length.

The shaded area on the map above shows the Southwest culture area.

The shaded area on the map above shows the Southwest culture area.

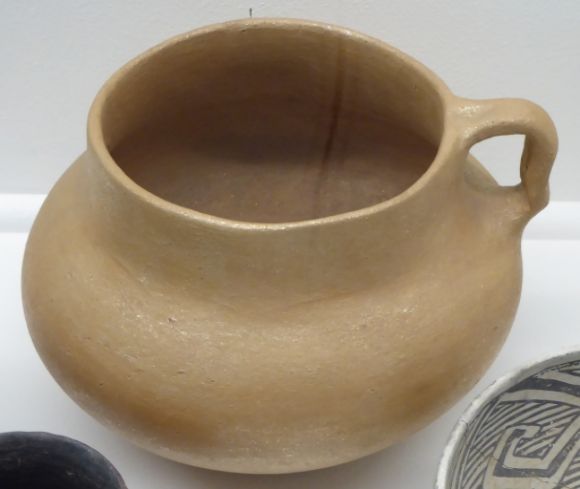

Pueblo pottery is one of the best known American Indian art forms. For many centuries, Pueblo people have made and used a wide variety of pottery containers, including bowls, jars, cups, ladles, and canteens. In addition, Pueblo potters also produced figurines, effigy vessels to be used for religious purposes, pipes, and prayer meal bowls. The pottery is often highly decorated and traded throughout the region.

Pottery varies among the Pueblos according to differences in raw materials, technology, and aesthetics. Each of the Pueblos has its own distinctive decorative styles. In addition, within a Pueblo the work of a particular potter, or the potter’s family, can sometimes be recognized.

In order to promote even drying and to minimize warping, temper is added to the clay. Temper may include sand, pulverized rocks, and ground potsherds. Temper varies according to region—and the type of clay and other materials available in the region—as well as to the personal preferences of the potter. In some areas, such as the Hopi mesas, sand naturally occurs in the mined clay and therefore the potters rarely need to add additional temper. At Taos and Picuris, the clay is naturally tempered with inclusive mica and the result is a very durable ware suited for cooking. At Zuni, the potters generally use ground potsherds: this means that pottery which might be hundreds of years old is incorporated into the new pottery. At Santo Domingo and Cochiti, volcanic tuff, usually called “sand”, is used for temper, while at Zia and Santa Ana, potters use a water-worn sand.

Firing the pottery is a crucial step in Pueblo pottery. This is a process which takes about six hours. The process of firing the pottery is described by Rick Dillingham in his essay in I Am Here: Two Thousand Years of Southwest Indian Arts and Culture:

“The firing of pottery is a short process, taking only a few hours, but careful monitoring of the firing is exhausting and those hours are intense. The ware is stacked on grating, made from old pottery sherds and specially made pottery baffles, to allow for even air circulation and heating.”

In an article in American Indian Art, Hopi potter Karen Kahe Charley and anthropologist Lea McChesney report:

“Firing brings an artist’s inner thoughts and feelings, contributed with her breath to the formation of a new being through the long duration of her labor and now distilled within the pot’s interior, to the surface and sets them as the public feature of her work.”

Pueblo pottery since the later 1800s has become renowned as collectable art work and this has created some conflicts with traditional Pueblo culture. The collectors who buy Pueblo pottery, almost all of whom are non-Hopi, want to know who made the piece and therefore a signature on the pot is important to them. In an article in American Indian Art, Dwight Lanmon and Francis Harlow note:

“Traditional Pueblo culture views the individual as a vital part of the whole, and personal recognition has largely been shunned. This attitude changed slowly in the 1900s and recognition of the work of individual potters has now become commonplace.”

Shown below is some of the Pueblo pottery which is on display at the Maryhill Museum of Art near Goldendale, Washington.

Shown above from left to right are pots by: (left) Adelle Lalo Nampeyo (Hopi); (center) Caroline Loretto (Jemez), and (right) Stephanie Naranjo (Santa Clara).

Shown above from left to right are pots by: (left) Adelle Lalo Nampeyo (Hopi); (center) Caroline Loretto (Jemez), and (right) Stephanie Naranjo (Santa Clara).

Ancestral Puebloan

The Anasazi or Ancestral Puebloans flourished in the Southwest from about 700 to 1350 AD. With regard to the term Anasazi, Joe Sando, in his essay in We, The People: Of Earth and Elders—Volume II, writes:

“When we talk about the ancient ones we don’t use the word ‘Anasazi’. We try to tell the teachers not to use it in the Pueblo classroom because it is a corruption of a Navajo term that means ‘Enemy of our ancestors’ and we don’t want Pueblo students calling Pueblo ancestors enemies.”

Shown above is black-on-white Ancestral Puebloan pottery.

Shown above is black-on-white Ancestral Puebloan pottery.

Salado Culture

About 1250 CE, a movement expressed in the archaeological record as Salado ceramics, moved throughout the major cultural areas including the Hohokam, Mogollon, and Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi). Archaeologist Todd VanPool, in an article in Archaeology, reports:

“The new system was reflected in pottery that merged design elements from the Ancestral Puebloan area with the designs and vessel types traditional to the Hohokam and Mogollon.”

Pottery is made in local forms, but decorated with consistent religious icons. The new religious movement, called the Southwestern Regional Cult by some archaeologists, seems to integrate people who are socially and ethnically distinct. The new system focuses on fertility and cooperation and it emphasizes connections beyond the village level. Archaeologist Todd VanPool writes:

“I believe the answer is that the Salado tradition was an explicitly female phenomenon, a ‘poor woman’s religion’ created by women seeking peace during a period of intense social upheaval caused by one of the most violent periods in the history of North America.”

Shown above is a detail of the double Salado bowl.

Shown above is a detail of the double Salado bowl.

Acoma

The name Acoma comes from Akome which means “people of the white rock.” The pueblo sits on top of a mesa which stands 365 feet above the surrounding valley. In his book Southwestern Indian Tribes, Tom Bahti writes:

“The best known craft of Acoma pueblo is pottery making. Many potters still produce large quantities of the carefully decorated, thin-walled ware.”

In the late 1870s, Acoma potters began using a parrot design. Rick Dillingham reports:

“The parrot is a familiar design element in Acoma ceramics and may have been suggested by imported trade cloth.”

This design was then copied by the potters at Zia who refer to these birds as “Acoma parrots.”

In his book American Indian Art, Norman Feder reports:

“The thinnest pottery in the Southwest is produced at Acoma, which is usually enough to identify it regardless of its design.”

Shown above is a polychrome olla with parrot motifs made about 2014 by Beverly “B.D.” Garcia.

Shown above is a polychrome olla with parrot motifs made about 2014 by Beverly “B.D.” Garcia.  Shown above is a black-on-white jar made about 1990 by Viola Ortiz.

Shown above is a black-on-white jar made about 1990 by Viola Ortiz.

San Ildefonso

According to one tradition, the ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso pueblo was at Mesa Verde. The native name for the Tewa-speaking pueblo of San Ildefonso is Pokwoge which means “where the water cuts down through.” The most famous San Ildefonso designs are the black-on-black designs pioneered by María and Julian Martinez. In 1919, they began making a polished ware decorated with matte black designs. Rick Dillingham, in his essay in I Am Here: Two Thousand Years of Southwest Indian Arts and Culture, writes:

“The Black-on-black technique involves an initial overall polishing of the vessel with red slip. Then, using a thinned mixture of slip, designs are painted over the polished surface. Before the firing the jar is a matte red-brown on polished red, and after the firing the more recognizable matte and polished black.”

In his book An Introduction to Southwestern Indian Arts & Crafts, Tom Bahti writes:

“The black finish is achieved during the firing by smothering the fire with powdered dung or shredded cedar bark. The black carbon smoke that results permeates the porous clay and turns it black.”

Norman Feder reports:

“These pots are painted after polishing, so that the painted area appears as dull black on a polished black surface. The painting is done by men after the women have made the basic ware, an unusual departure from the common practice where women make the pots from start to finish.”

In 1921, María and Julián Martínez began to teach others in San Ildefonso Pueblo the method of making black-on-black pottery which developed into major industry for the Pueblo.

In 1923, potters María and Julián Martínez began to sign their work.

In 1933, San Ildefonso potters Maria and Julian Martinez received the Best in Show award at the Century of Progress, Chicago World’s Fair.

At San Ildefonso, the potters use a combination of geometric and curvilinear design elements, as well as bird and floral motifs.

Shown above are blackware jars made in the 1940s and 1950s by María Martinez (1887-1980) and Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002) (jar on left) and María Martinez and Popovi Da (1923-1971) (jar on right).

Shown above are blackware jars made in the 1940s and 1950s by María Martinez (1887-1980) and Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002) (jar on left) and María Martinez and Popovi Da (1923-1971) (jar on right).

Cochiti Pueblo

Cochiti designs often include free-floating elements and ceremonial motifs such as clouds and lightning. In his book Cochiti: A New Mexico Pueblo, Past and Present, Charles Lange reports:

“Cochití pottery has traditionally been black-on-cream, often combined with brick-red surfaces on the exterior bottoms and the complete interiors of bowls and ollas.”

Cochiti designs often include free-floating elements and ceremonial motifs such as clouds and lightning.

Shown above is a storyteller figure made in 1979 by Helen Cordero (1915-1994).

Shown above is a storyteller figure made in 1979 by Helen Cordero (1915-1994).

Santa Clara Pueblo

The native name for the Tewa-speaking pueblo of Santa Clara is Ka’po whose meaning is unknown. Carved black pottery was introduced at Santa Clara about 1924-1926 by Serafina Tafoya. Rick Dillingham writes:

“At the time it was first made it must have seemed quite innovative, but now it is mainstream traditional Santa Clara pottery.”

Shown above is an incised blackware jar made in the 1980s by Stella Chavarria.

Shown above is an incised blackware jar made in the 1980s by Stella Chavarria.

Zia

Zia pottery is distinctive because of the use of a ground basalt temper. With regard to design, Rick Dillingham reports:

“Zia pottery designs are very distinctive in the use of bird motifs and the undulating ‘rainbow’ band, encircling many jars with bird and floral motifs.”

Zia designs are sometimes similar to those used in Acoma and Laguna.

Shown above is a lidded jar made about 2015 by Elizabeth Medina.

Shown above is a lidded jar made about 2015 by Elizabeth Medina.

Zuni

The name Zuni is the Spanish corruption of the Keresan word Sunyi. The native name for the pueblo is A’shiwi which means “the flesh.” In his book American Indian Art, Norman Feder reports:

“At Zuñi the base part of the pottery is slipped with black or brown in contrast to red or orange at the other villages. In addition, Zuñi pottery is usually decorated with a design laid out in equally divided sections, ranging from two to four. Designs include rosettes and animals with arrows drawn from their mouths to their hearts.”

With regard to Zuni pottery designs, Rick Dillingham reports:

“The design most associated with Zuni is a semi-realistic deer motif with a line leading from the heart to the mouth. This is most often called the ‘heart-line’ deer.”

The pottery shown above was made by unknown Zuni artists between 1880 and 1920.

The pottery shown above was made by unknown Zuni artists between 1880 and 1920.

Leave a Reply