In providing a broad overview of the hundreds of distinct American Indian cultures found in North America, it is common for museums, historians, archaeologists, and ethnologists to use a culture area model. This model is based on the observation that different groups of people living in the same geographic area often share many cultural features.

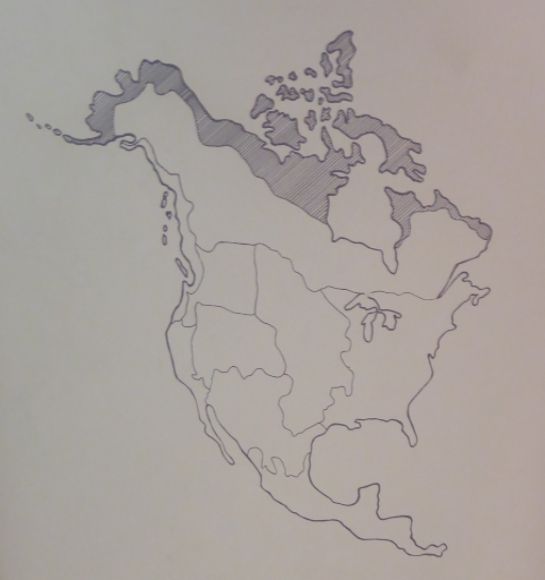

The map above shows the primary North American Indian culture areas.

The map above shows the primary North American Indian culture areas.

The Artic Culture Area includes the Aleutian Islands, most of the Alaska Coast, the Canadian Artic, and parts of Greenland. It is an area which can be described as a “cold” desert. Geographer W. Gillies Ross, in his chapter in North American Exploration. Volume 3: A Continent Comprehended, writes:

“The North American Arctic is usually considered to be the region beyond the northernmost limit of tree growth.”

The shaded area on the map above shows the Arctic culture area.

The shaded area on the map above shows the Arctic culture area.

The area has long, cold winters and short summers. During the summer, the tundra becomes boggy and difficult to cross. W. Gillies Ross describes the region this way:

“In general, the Arctic is characterized by mean monthly temperatures under 50ᵒ F (10ᵒ C); long, severe winters; short, cool summers; persistent ice cover on fresh- and saltwater bodies; prolonged winter darkness and summer daylight; ground underlain by continuous permafrost; and a comparatively small number of plant and animal species.”

In his Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, Carl Waldman describes the Arctic this way:

“The climate of the Arctic is fierce. Winters are long and bitterly cold, with few hours of sunlight.”

The native people of the Arctic are usually divided into the Aleut and the Eskimo. The Eskimo refer to themselves as Inuit and the Aleut call them themselves Unangan. All of the languages of this area belong to the Eskimo-Aleut language families. In his entry on this language family in the Handbook of North American Indians, Anthony Woodbury writes:

“The Eskimo-Aleut linguistic family consists of two distantly related branches, Eskimo and Aleut, each of which must have developed over a long period of time from a remote common ancestor, Proto-Eskimo-Aleut.”

Eskimo is sub-divided into Inuit-Inupiaq and Yup’ik. Yup’ik is made up of three mutually incomprehensible languages: (1) Sibertian Yup’ik which is spoken by the St. Lawrence Island and Siberian Eskimo; (2) Central Yup’ik which is spoken by a number of groups on the Alaska mainland from the mouth of the Yukon River south and east to the Alaska Peninsula; and (3) Alutiiq which is spoken along the south side of the Alaskan peninsula, on Kodiak Island, on the lower part of the Kenai Peninsula and in Prince William Sound.

The Inupiat (also spelled Inupiaq), which means “the people,” are composed of four main groups: Bering Straits people, Kotzebue Sound people, North Alaska Coast people, and Interior North Alaska people. At the time of first contact with Europeans, the population of these four groups was nearly 10,000 with the Kotzebue Sound people having a population of about 4,000.

Aleut was aboriginally spoken by peoples living on the Aleutian Islands. While navigation across the Aleutian area is hampered by difficult waters, there are only two main dialects of Aleut: Eastern Aleut and Western Aleut. Anthony Woodbury reports:

“The uniformity of the Aleut dialects surviving into the historical period suggests a relatively recent spread of Proto-Aleut from its place of origin over the entire island chain before the historical period, replaced all the dialects or language spoken there.”

Geographer W. Gillies Ross writes:

“Most of this vast domain was thinly inhabited by Eskimo hunters (Inuit), whose ecumene extended as far north as the Parry Channel, the series of Waterways running west from Baffin Bay (Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, Viscount Melville Sound, M’Clure Strait) and dividing the southern ties of Arctic islands from the two northern tiers.”

In an article in Archaeology, Daniel Weiss writes:

“The Inuit, also known as the Thule people, originally came to Alaska from Siberia, where they had developed a range of powerful adaptations to life in the Arctic, including hunting implements such as bows and arrows and lances. They thrived in coastal settlements, where they could speed across the ice in their dogsleds and hunt seal, whales, and walrus in their skin-covered kayaks and larger boats called umiaks.”

Between 1300 and 1350, the Inuit spread from Alaska to Greenland and by 1450 there were Inuit groups living in Labrador.

The Yuit (southern Eskimo) are speakers of the Yup’ik languages and numbered more than 30,000 at first contact with the Europeans. The Yuit are usually divided into two basic groups: Bering Sea groups and Pacific groups. The Pacific groups include the Koniag who occupied the Kodiak archipelago and the southside of the Alaska Peninsula, the Chugach who occupied Prince William Sound, and the Unegkurmiut who occupied the south coast of the Kenai Peninsula.

There are also a number of Athabascan-speaking groups in the interior of Alaska between the Brooks Range on the north and the Alaska Range on the south.

Eskimo/Inuit

According to the display in the Maryhill Museum of Art:

“Much Eskimo art was created in ivory and as a result it was small in scale. Arctic life, both human and animal, was the most common subject matter in art. Although wood was scarce, wooden masks and containers had an important place in Eskimo art. Among the Aleut, basketry was a major art form.”

Shown above are some of the displays of Arctic artifacts in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Shown above are some of the displays of Arctic artifacts in the Maryhill Museum of Art.  Shown above are some of the displays of Arctic artifacts in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Shown above are some of the displays of Arctic artifacts in the Maryhill Museum of Art.  Shown above are some of the displays of Arctic artifacts in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Shown above are some of the displays of Arctic artifacts in the Maryhill Museum of Art.  Shown above is an Inuit basket on display in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Shown above is an Inuit basket on display in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Aleut

The Aleutian Islands are a chain which extend into the Pacific Ocean from the tip of the Alaska Peninsula. This is an area which is cold and damp, with few trees. In spite of this seemingly inhospitable environment, people have been living on the islands for at least 9,000 years.

The Native people who inhabit the Aleutian Islands are known as Aleuts, which may come from a Native word meaning “island” or from a Russian word meaning “bald rock.” They call themselves Unangan which means “Original People.” In his book The Native People of Alaska, Steve Langdon writes:

“The Aleut are distinctive among the world’s people for their remarkable successful maritime adaptation to this cold archipelago.”

The ancestors of the Aleut may have settled on Anagula Island more than 9,000 years ago.

The Aleuts had a maritime economy which included hunting sea mammals (sea otters, seals, sea lions, walruses, and whales) and fishing. Of the sea mammals, the Stellar sea lion was most important. Steve Langdon reports:

“This animal provided not only food but also a vast variety of other products, including boat covers (hide), line and cord (sinew), oil (blubber), tools (bones), fishhooks (teeth), boot soles (flippers), containers (stomach) and materials for garments (esophagus and intestines).”

The Aleuts are also known for making elegant baskets. In making baskets, the weavers used rye grass growing on the beaches. In his Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, Carl Waldman writes:

“The stems of the grass were split with the fingernails to make threads, and some of the threads were dyed in order to make baskets with intricate woven designs.”

Shown above is an Aleut basket made about 1940 which is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Shown above is an Aleut basket made about 1940 which is on display in the Portland Art Museum.  Shown above is an Aleut basket made about 1900 which is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Shown above is an Aleut basket made about 1900 which is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Inupiaq

Shown above is an Inupiaq mask made about 1900 from wood. This is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Shown above is an Inupiaq mask made about 1900 from wood. This is on display in the Portland Art Museum.  Shown above is an Inupiaq pipe made about 1900 from ivory, wood, and paint. The art work on the pipe shows a walrus hunt in which the hunter appears to be using an atlatl. This pipe is about eight inches in length. This is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Shown above is an Inupiaq pipe made about 1900 from ivory, wood, and paint. The art work on the pipe shows a walrus hunt in which the hunter appears to be using an atlatl. This pipe is about eight inches in length. This is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Central Yup’ik

For the Central Alaska Yup’ik Eskimo, spirituality was focused largely on the need to secure food for hunting. As with other animistic hunting peoples, animals were felt to have souls which would be reincarnated. Thus, rituals sought to appease the soul of the animal so that it would give itself to the Yup’ik hunters who needed its meat.

Many of the Yup’ik ceremonies involved the use of masks. In an article in American Indian Art, museum curator Eva Fognell writes;

“The elaborate masking tradition of the Central Yup’ik of southwestern Alaska centers on the spiritual quest of the hunt.”

Eva Fognell goes on to write:

“Masks symbolize the transformation of animals into humans, as well as shamanic ties between humans and the spirits of nature that exercise control over animals.”

Shown above is a mask made about 1940 from wood, feathers, paint, and sinew. This is on display in the Portland Art Museum.

Shown above is a mask made about 1940 from wood, feathers, paint, and sinew. This is on display in the Portland Art Museum.  Shown above is a Loon Mask which is on display in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Shown above is a Loon Mask which is on display in the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Leave a Reply