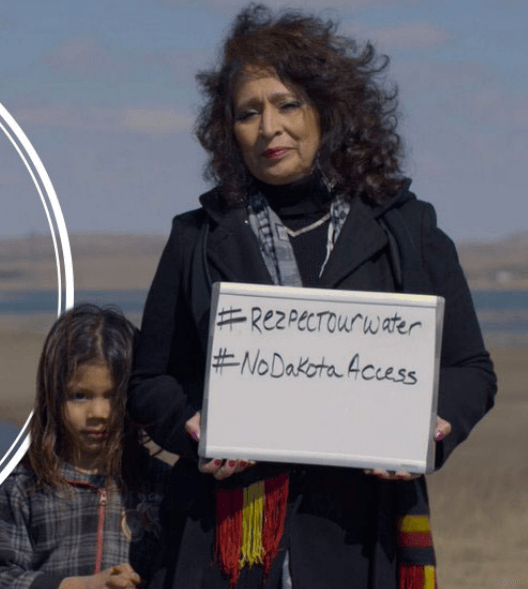

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard: A Rebel with a Cause

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard: A Rebel with a Cause

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard established the Sacred Stone camp on her own property near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in order to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline. On May 24, I had the privilege of hearing her speak when she was recognized by Conservation Colorado as their 2017 “Rebel With A Cause”.

Just a week later — on June 1 — two notable and interrelated events took place. As widely reported including on Daily Kos, Donald Trump announced that the the US would withdraw from the Paris climate accord. Less noticed was that June 1 is the first day that the Dakota Access Pipeline began commercial service. In reversing President Obama’s decision and directing the Army Corps of Engineers to authorize the pipeline, Trump added another chapter to our nation’s sorry history of mistreatment and betrayal of our native people — and June 1 was the day that decision became action.

The Standing Rock Sioux have not abandoned their fight against the pipeline, and as Meteor Blades shared they won an important legal victory in mid-June (though oil continues to flow through the pipeline). But LaDonna Brave Bull Allard’s speech put the efforts of the Water Protectors in a broader context beyond just the immediacy of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

If you can, I encourage you to watch her full half hour speech:

For those who cannot watch the full speech or who prefer reading, I will share some of the high points.

She opened by explaining that she came to this fight not as some environmental activist or hero, but for deeply personal reasons when she discovered where the pipeline was routed by her land:

How can they do that? And I tell everybody, my mind went blank. I no longer thought. I no longer made sense. All I could think about was, “My son is buried there. How dare they.” My first obligation in life is a mother, and even though my son has left for the spirit world, I will protect his grave until I am gone. And so that is how I stood. It was not some grandiose idea about saving the world. It was simple. I loved my son.

She then offered some history — the specifics of which I was sadly ignorant before, but the themes of which are all too familiar with anyone who has learned about our nation’s treatment of native peoples. She explained that her grandmother was a survivor of the 1863 Whitestone massacre, when troops led by General Alfred Sully attacked a camp of Lakota — who had nothing to do with conflicts in Minnesota to which the troops had been sent to respond — and indiscriminately killed more than 300 natives including women and children.

It was a massacre that happened and then they forgot they killed us. Because we were the wrong Indians … the people of Cannonball North Dakota are all descendants of this massacre, and so I was telling [Amy Goodman] the story of the massacre and my grandmother. My grandmother was 80 years old and she would still scream at night, “Run! Run! The soldiers are coming! Run! Hide!” This is the legacy we grew up with.

Her grandmother was taken to a prisoner of war camp at age 9, and when released she came back to the northern side of Standing Rock. Allard explained, “We begin again, we can do this, we are survivors. And so we began. We planted our gardens and made our homes.”

But their betrayal wasn’t over. In 1944, the Pick Sloan Flood Control Act was passed — authorizing flood control reservoirs in the Missouri River system and setting the stage for land to be condemned (with some compensation delayed as long as into the 2000s), fertile bottomland to be flooded including more than 350,000 acres of tribal lands, and the native people forced to move again onto the dry plains overlooking their former river valley homes. Allard described it:

They passed the Pick Sloan Act to build a dam above us and build a dam below us and to make us damn Indians again. When they did that, they moved us from our bottomlands and our homes that we owned and they put us in communities that we could not own. And they moved us to the top of the hill that had a gumbo clay soil that we could no plant gardens and no longer have trees. And then they flooded our homes. As we stood on the hills and watched our trees drown and watched the animals drown and watched them take our livestock, and we cried, and we said, it’s OK, we can do this again. We are survivors, we are strong, we can do this again.

But when the Dakota Access Pipeline came, Allard was not ready to do it again, to move on and rebuild. “I’m not moving, I’m not backing down. Right now at this point in my life, the roots grow right out of my feet down into the ground and I’m not moving.”

Then came the next betrayal — the day of the dogs. Allard explained that tribal members had carefully mapped grave sites that needed to be protected, and had provided that information to the courts. The judge had provided it to Dakota Access. And the company picked up the equipment that was working 20 miles away and moved it pronto to the mapped sites and began digging up the grave sites. “Who does that?” she asked.

I got up to the front lines and the first thing I did was run into Linda Black Elk who was crying because they had dug up all these graves. And people were all along the fence and the women and children were crying and I watched this man get out of this white truck and take pepper spray and just go down the line and spray all the women and children. And I stood there and walked out into the field and there was a great big grey-headed dog on this side, and there was a woman with a black German Shepherd that was siccing dogs on people and blood was dropping from his mouth, and I was thinking “Where Am I? Is this America? Is this who we are?”

But in the face of violence and betrayal, Allard and the Water Protectors have held on to hope. Seeing the people, especially the young people, from across the country and around the world who came to stand with the Water Protectors reminded her, she says that “the power is still in the people. And the power has always been in the people. When the people stood up, we had young people from everywhere coming and they came in song and dance and prayer.”

The camps had as many as 15,000 supporters at their peak, sharing food, and filling the air with prayer, ceremony, song, and dance. Then the government ordered the camps closed. The Water Protectors, she said, decided to “stay in prayer … move the camp … do not resist … on that day that they evicted us we packed up trailers of food and we delivered it to everyone in the community.”

So what did they do after the camp? “We became seeds,” Allard said.

Since the camps ended on standing rock, 250 camps spread out across the world. We have Sacred Stone representatives in almost all the camps. We are providing training and resources across the world because this is not an American movement, this is a world movement.

As she wraps up her speech, she comes full circle, realizing that her efforts are bigger than herself and her family — indeed, as big as the whole interconnected world.

Arvol Looking Horse told me as we were talking about my love for my river, he said “You understand it. You understand the tree. So the tree has all these roots that are growing down and you have the mainstem of the tree that goes up and you have the branches. That is us. The Missouri is the branch of this great tree and our branch is sick. But we can make it well. The mainstem is the Mississippi. It is dying because its roots in the Gulf of Mexico are dying. But if we can heal this branch, we can heal the mother tree. And by doing that one thing, we can heal the world.”

And I thought, “Wow I understand now.” It is not about me. It is not about my dear son. It’s about everything. So we’ve only just begun. I’m asking as everybody has woken up and spread these seeds — don’t go back to sleep. The world is counting on you now.

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard shared hard-earned wisdom that we should all take to heart. Whether you are protecting water in your community — or fighting to preserve health care — or working to promote social justice for people of color, we must remember that the “power is still in the people” and that we cannot go back to sleep. We will not win every battle — but just as the Water Protectors continue to spread their message and inspire others even after the Dakota Access Pipeline was approved, our continuing efforts (win or lose) will plant seeds. Jon Ossoff and those who fought for his election have planted seeds in Georgia. Rob Quist and the Montanans who fought with him planted seeds in Big Sky country. The millions of women who marched on inauguration weekend planted seeds of resistance in communities coast to coast. We need to keep planting and nurturing those seeds, finding our resilience as the Lakota people have had to do for generations. And if we each focus on the branches we can heal and keep fighting — together we CAN heal the world.

And the world is counting on us.

Thanks to Meteor Blades for his helpful editorial comments on a draft of this piece. Any remaining errors are the responsibility of the author alone.

Leave a Reply