( – promoted by navajo)

photo credit: Aaron Huey |

The Battle of Lost River

In Part II, I had concluded with the Third Generation’s great crisis. The Modoc were destroyed as an independent people, and forced into being part of the Klamath Tribes on Klamath Indian land, to the north, in Oregon. Keintpoos with Cho’ocks and Scarfaced Charley and their families had left the reservation to go back to lost river. The Battle of Lost River, which broke out when the army and a Linkville militia attempted to force the return of the people, and their disarmament, ended with deaths and injuries on both sides. The Modoc all retreated near Tule Lake to Lava Beds. Hooker Jim’s band massacred settlers in the area around the lake, right at the heart of the Applegate Trail in Modoc country.

It was the last day of November, 1872.

FIGURES

MODOC

- Old Schonchin

- Schonchin John, his brother

- Keintpoos, or Captain Jack

- Winema, known as Toby Riddle, interpreter

- Cho’ocks, or Curley-Headed Doctor, spiritual leader

- Hooker Jim

- Scarfaced Charley

- Boston Charley

- Slolux

- Brancho

- Black Jim

- Shacknasty Jim

- Bogus Charley

- Steamboat Frank

- Ellen’s Man

- Mary, Keintpoos’ sister

- Lizzie, Keintpoos’ wife

- Old Wife (of Keintpoos)

- Rose, Keintpoos’ daughter.

- Stimitchuas, or Jennie Clinton

- Elvira Blow

YANKEES

- Ulysses S. Grant, US president

- General of the Army William Tecumseh Sherman

- E.S. Canby, Brigadier General, peace commissioner

- Alfred B. Meacham, Oregon Indian Agent, peace commissioner

- Rev. Thomas Eleazer, peace commissioner

- Elijah Steele, Indian Agent for Northern California

- Lindsay Applegate, founder of the Applegate trail, Oregon Indian Subagent

- Frank Riddle, peace commissioner, settler, husband to Winema/Toby

- L.S. Dyar, peace commissioner

- Eadweard Muybridge, photographer

End Game

Lava Beds proved a brilliant strategic move by the Modoc. Lava Beds is a naturally complex series of trenches, caves, and volcanic features. One species of fern present in one cave is not found except for hundreds of miles to the west, in far more moderate lands. Perhaps this is an appropriate symbol of the Modoc’s refuge. Only a few dozen Modoc warriors were able to elude and frustrate the US Army, modernized though the Army was, and well equipped after the Civil War and Indian wars, in the dead of winter.

Already they wanted Keintpoos for murder; in keeping with tradition, he had slain a healer who had failed to cure his sick child. His family, including his wife Lizzie and young daughter Rose, dwelled in their own cave. The cave is exposed to the sky, but they all remained alive and hidden during the ordeal.

Stimitchuas and other Modoc children were sent to retrieve the cartridges from fallen soldiers.

Ojibwa has already delivered an overview of the Modoc War of 1872-1873, so I will try to emphasize other aspects to the story while explaining the basics. From Ojibwa:

The spiritual leader of the group was Curley Headed Doctor [Cho’ocks]. In the lava beds, he had a rope of tule reeds woven, dyed red, and stretched around the campsite. He claimed that no American soldier could cross this rope. Since no soldiers cross this rope during the conflict, the Modoc assumed that it worked.

…In one encounter, the 400 soldiers who were sent in to subdue the Modoc encountered a thick fog and soon retreated in panic and disarray. From the Modoc perspective, Curley Headed Doctor’s medicine had worked. He had brought a fog to confuse the enemy, and then he turned the soldiers’ bullets so that no Modoc was hurt.

In another instance, a large patrol blundered into a carefully planned ambush. The army and the press labeled this a massacre. The soldiers had left on the maneuver as though they were going to a picnic rather than a battle. One of the Modoc leaders, Scarface Charley, had called down to some of the survivors: “We don’t want to kill you all in one day” and through this generosity several soldiers escaped.

In one incident, the army soldiers found an old woman-described as being 80 or 90 years old-in the rocks near the stronghold. The lieutenant asked: “is there anyone here who will put that old hag out of the way?” A soldier then placed his carbine to her head and shot her.

Embedded Journalism

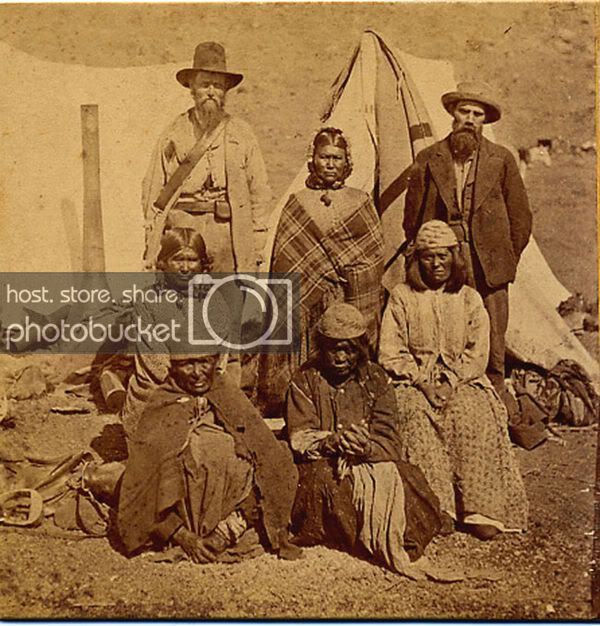

Toby Riddle, 4 Modoc women and 2 settlers

Toby Riddle, 4 Modoc women and 2 settlers

Originating in the Crimean War twenty years prior, modern war photography and journalism had become something refined by the time of the Lava Beds War. Eadweard Muybridge (born Muggeridge in England) was one of the most influential photographers in the early statehood period of California. One generation later, his interest in capturing motion on film would prove deeply influential to the rising motion picture industry. A true archetype of the Old West, Muybridge was a constant self-reinventer. Also a fabulous deceiver and liar, he later murdered his wife’s lover and got away with the crime. During the beginning of the lava beds campaign, Muybridge captured some fascinating images to be sold to magazines and newspapers. For instance, take this photo of Toby Riddle between two California militia men, with 4 old Modoc women. However, some were fabricated: Muybridge had a non-Modoc man pose at some rocks as though he were shooting at Army soldiers. “On the start for a Reconnaissance of the Lava Beds “ reads the title for one photograph.

Journalists followed the Army around and reported on events as people around the world followed their stories with relish. Interestingly, reporters even went into Lava Beds to document and interview Modoc people.

Divides, Assassination

Winema, called Toby Riddle, was one of the Modoc on the other side of the conflict. Similar to the contemporaneous Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, Toby Riddle was a US Army interpreter, and her husband Frank was a settler. During the war she mostly acted as a messenger. Although she had already borne a son she ran across the lavascape. Because she was a cousin to Keinpoos, Winema remained safe venturing into Lava Beds.

Brigadier General E.S. Canby was in charge of the Lava Beds campaign. Meacham, described in Part II, again appears as a participant.

The war was divisive for Modoc people. Most remained under the authority of Old Schonchin up north during the war, in turn outnumbered by the Klamath in the “democratic” government. Schonchin John had joined the Modoc encampment. Within the Lava Beds community there were strong divisions. Keintpoos wanted the war brought to a carefully-arranged end that would secure peace and the right to live in the area of Lost River with his family. Others wanted to drive out the European-Americans.

Months of peace negotiations unfolded. Canby grew annoyed by the interference from the Oregon governor, who was eager to hang multiple Modoc at the moment of surrender.

In the meantime, Canby’s men seized Modoc horses while the negotiations played out. To the Modoc this was unacceptable. At a gathering, the Modoc warriors proposed assassinating Canby at the peace commission. In the northwest and basin, killing an enemy’s leader typically ended conflict. Furthermore, the Third Generation did not forget the Ben Wright Massacre and its false flag of peace in the dead of night. Keintpoos differed from those proposing the killing. Some of the group, possibly Hooker Jim among them, considered Keintpoos cowardly and unfit to be their leader. They tossed a female woven hat at the leader as shaming. By now, the warriors were mostly in favor of assassination. It would be a dangerous move.

Winema learned of the assassination plot and warned Canby and others. She went unheeded. Elijah Steele warned Canby by letter, too, but in response Canby wrote that his duty overrode concerns for safety.

At their peace negotiation on Good Friday, 1873, Canby left many soldiers waiting just off from the peace tent, which was situated halfway between the Modoc and Army encampments. The mere presence of so many troops would deter any threats, was his thought. Also there were the Riddles, the Methodist minister Eleazer Thomas, and agent Alfred Meacham, L.S. Dyar, and two soldiers carrying concealed weapons. Keintpoos tried one last time to make progress. Schonchin John wanted a reservation for his band at Hot Creek. However, the commissioners were single-minded and resolved to accept nothing less than total surrender.

Keintpoos revealed his revolver and shot Canby dead. Slolux and Brancho pulled forth rifles and fired. Reverend Thomas also died from gunfire, and Meacham was wounded. Frank Riddle and Commissioner Dyar fled; Winema remained behind. Someone began scalping Meacham but Winema intervened and saved him by warning of the coming soldiers. Keintpoos, Black Jim, Boston Charley, and the rest escaped.

Punishment

Replacement General Jefferson C. Davis swelled the ranks to 1,000 troops. William Tecumseh Sherman, General of the Army, urged Davis to kill every Modoc man, woman and child in retaliation. Sherman instructed a colonel, “[y]ou will be fully justified in their utter extermination.”

The first Modoc defeat happened at the Battle of Dry Lake on May 10. Despite the routing, only several Modoc died including the band leader Ellen’s Man. Recognizing that a precise time had come, Hooker Jim and his band left Lava Beds and changed allegiance. Hooker Jim, Bogus Charley, Shacknasty Jim and Steamboat Frank and others helped end the war earlier by enabling US Army to track down Keintpoos. They and their families were allowed to return to Klamath reservation unguarded. In exchange for Captain Jack, these Modoc received amnesty for the Tule Lake killings.

Keintpoos surrendered at the beginning of June, 1873.

Military tribunal. Winema interpreted. Keintpoos, Schonchin John, Boston Charley, Black Jim, Slolux and Brancho were sentenced to death. In yet another ironic turn, they were convicted of war crimes, the only time American Indians would be. None had legal counsel.

Ulysses S. Grant would later commute the sentences of Slolux and Brancho, giving them life imprisonment at Alcatraz Island, far to the southwest. The rest were hanged. Their heads were severed and shipped to Washington, D.C. Over a century later, Keintpoos’ relatives would finally retrieve custody of his head from the Smithsonian.

Keintpoos’ wife Lizzie, his Old Wife, his daughter Rose and sister Mary were, with all the remaining Modoc from Lava Beds, boarded on cattle cars and shipped to Oklahoma on a non-stop journey. It is said that they became so starved that upon being released on a field in Oklahoma, the captives found a cow in the field, killed and ate it there on the ground. Rose died in Oklahoma, Keintpoos’ only child.

Curley-Headed Doctor fell into disfavor. His power had failed the Modoc, so the people believed. The Modoc in Oregon converted to Methodism and those in Oklahoma were converted by the Quaker. As time passed on, Curley-Headed Doctor’s heart grew heavy. One cold morning, he went outside to behold a gigantic flock of crows. Their movement signified a great event, and he died soon after. He is still buried in Oklahoma. The Third Generation mostly passed by 1900.

Note

Winema lived the rest of her life on the Klamath Reservation with Frank and her son Jeff. Influenza claimed her in 1920.

The last Modoc War survivor was Stimitchuas, remembered as Jennie Clinton. It’s unknown when she was born, but she was one those shipped to Oklahoma after the war, and returned to Oregon in 1918. In 1922, Jennie Clinton divorced her husband. She spent the rest of her life in a cabin on the Williamson River. She made beadwork but did not weave.

Elvira Blow was an even older Modoc War survivor (she already had children before the war) who continued traditional basket-making into the 1930s.

In the 20th century, Oklahoma Modoc were able to return to Oregon. About 50 remained behind at Quapaw. That is why there are two separate Modoc tribes within two different nations today: one in Oregon, one in Oklahoma.

Jennie Clinton died in 1950, somewhere between the ages of 89 to over 100. She was the last, having survived forced migration, hunger, poverty, and bloodshed. The Fourth Generation was gone and the Fifth was mostly gone. Four years later, an act of congress would terminate the existence of the Klamath Tribes.

Subsequent generations of Modoc history will be described in upcoming diaries.

Leave a Reply