The nineteenth-century wild west shows did a great deal to firmly entrench the stereotype of the American Indian in American culture. This stereotype, loosely based on generic Plains Indian cultures, portrays Indians as savages, as a vanishing people destined to go extinct in the face of American superiority, and hindrances to the inevitability of Manifest Destiny.

The most famous of the wild west shows was organized by William F. (“Buffalo Bill”) Cody. He began to put together his Wild West show in 1882. The show included Indian dances and ceremonies, but portrayed the cowboy as the true hero of the West and the Indians as warring savages. Buffalo Bill viewed his show as being highly educational. The dances and ceremonies were almost exclusively from the Plains tribes and thus Plains Indians came to represent all Indians. In the show, good and evil were visually represented as simplified moral categories. Non-Indians are considered good and Indians evil. The shows glorified the recent past of the American west and justified the subjugation of the Indian tribes in the name of progress and Manifest Destiny.

In 1883, Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West, Rocky Mountain, and Prairie Exhibition shows thrilled crowds at the Omaha, Nebraska fairground arena. The show used Pawnee warriors and cowboys to recreate the events of the recent past. The show employed dozens of Indians who rode, shot, and whooped their way around the arena. The show was part circus, part ethnographic display, and a self-promoting stage play for Buffalo Bill. While the show was described as “awkwardly staged and poorly performed”, it moved on to Council Bluffs, then to Springfield, Illinois and then east to New York and Boston.

In 1884, an Indian troupe featuring Lakota chief Sitting Bull toured 25 cities from Minneapolis and St. Paul to New York. The troupe was made up of eight Indians and two interpreters. In the performances and publicity, Sitting Bull was portrayed as the “Slayer of Custer.” In general, the press reports from the tour tended to focus on Sitting Bull: his dress, his speech, his table manners, and so on. The tour, arranged by Colonel Alvaren Allen, was not financially successful.

The following year, Sitting Bull toured with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West. In the show, he played a villain and audiences hissed at him when he appeared. Sitting Bull was paid $50 per week and was given the concession to sell photographs and autographs of himself. Advertising for the shows emblazoned Sitting Bull’s name almost as prominently as Buffalo Bill’s, showing that Sitting Bull was a major attraction.

Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill are shown above.

At the end of the tour, Cody presented Sitting Bull with a sombrero and a trained circus horse. In response to queries from the press, Sitting Bull explained that he was sick of the houses, the noise, and the multitudes of people. In the cities, Sitting Bull saw poor people begging on the streets and he was shocked to realize that the Americans did not take care of people in need. He gave away much of the money he earned to street beggars.

In 1886, the Indian Office (now known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs) began to regulate Indian employment in wild west shows. Among other things, it required the shows to provide chaplains and interpreters for the Indians.

For the 1886 season of the Wild West, Buffalo Bill Cody wanted to use Sitting Bull again as a headliner. However, his request for Sitting Bull was denied by the Indian agent who felt that Sitting Bull was

“too vain and obstinate to be benefitted by what he sees, and makes no good use of the money he thus earns.”

The Indian agent, and the Indian Office, did not feel that the Indians should have any say in their employment. At this time basic freedoms, such as the ability to find employment or to leave the reservation, were denied to Indians.

For the 1886 season, American Horse (the younger) joined the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West as the Indian headliner to replace Sitting Bull. American Horse’s feelings about the eastern cities:

“I see so much that is wonderful and strange that I feel a wish sometimes to go out in the forest and cover my head with a blanket, so that I can see no more and have a chance to think over what I have seen.”

At this time, Black Elk also began dancing in the show. One of his reasons for joining the show was to be able to learn some of the non-Indian secrets. Black Elk would later become well-known among non-Indians as a holy man.

Not everyone liked the wild west shows. From the floor of the House of Representatives, New York Congressman Darwin Rush James criticized Buffalo Bill’s Wild West for its savagery and for allowing Indians to frequent saloons and whorehouses. James, who did not see the New York City production in question, called for a ban on the government licensing of such shows.

The following year, Congressman Darwin Rush James asked the Secretary of the Interior to explain to Congress why some “Wild Indians” had been absent from their reservations and had been

“presenting before the public scenes representing their lowest savage characteristics.”

The request was in response to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

In direct violation of the 1879 Standing Bear decision which declared that Indians were people and had a right to habeas corpus and due process of law, Indian Commissioner Atkins, in 1887, prohibited Indians from leaving the reservations to perform in “Wild West” shows without the formal consent of the government. He told them:

“When the Great Father thinks it best for Indians to leave their reservations, he will grant them permission and notify their Agent.”

In 1889, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show toured Europe with a group of Lakota, including Rocky Bear, Red Shirt, and Featherman. Parisian artist Rose Bonheur, famous for her animal and nature paintings, spent many hours at the Indian encampment painting portraits of the show’s Indians. After witnessing a French political meeting, Rocky Bear commented:

“you smoke at the same time, you speak all at the same time, and you understand anyhow.”

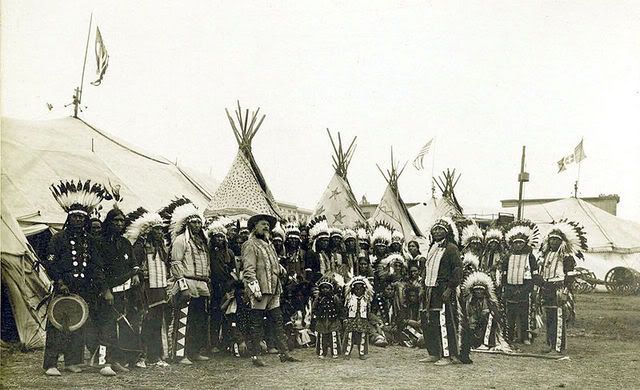

The 1890 Wild West Indians are shown above.

In 1891, Buffalo Bill Cody convinced the army to release 25 Sioux Ghost Dancers who were being held at Fort Sheridan. The Ghost Dancers were to be incorporated into his Wild West for its upcoming European tour. This action removed the Ghost Dancers from the political realm of the reservation. They were now a part of a spectacle which moved across Europe.

When Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performed at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition, the Indian Office ordered John Shangreau, a Lakota of mixed heritage who acted as an interpreter, to cut his hair because he would be representing “advanced Indians.”

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was not unique and there were a number of others that also toured the country. In 1895, Montana’s Wildest Wild Show featured Cree who had taken part in the Canadian Riel Rebellion and advertised them as

“the only people in the United States without a country.”

The show played in Chicago, New York, and New Orleans. It disbanded in Cincinnati, Ohio leaving the Cree stranded.

In 1897, Nez Perce Chief Joseph, who was in New York City to participate in a parade for the dedication of Grant’s Tomb, was invited to Madison Square Garden to watch Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. When Buffalo Bill realized that he was in the audience, he rode over and paid his respect.

In 1902, Luther Standing Bear, a Lakota who graduated from Carlisle Indian School, joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West as an interpreter. Luther Stand Bear would later write a number of books about Indians.

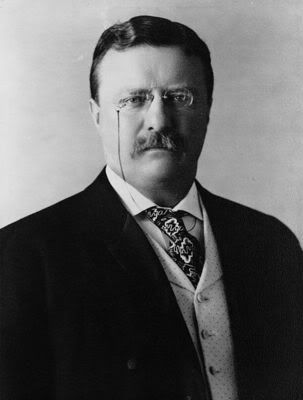

Buffalo Bill in 1903 is shown above.

Among those who learned about Indian cultures and histories from the wild west shows were teachers. In 1905, the Miller Brothers staged a roundup for the National Editorial Association at their 101 Ranch Real Wild West in Texas. The roundup included a buffalo hunt in which Apache chief Geronimo shot a buffalo. Geronimo, who was still a prisoner of war, was brought up from Fort Sill with a soldier escort for the event.

The increasing popularity of motion pictures, many of which were westerns with Indian themes, led to decreasing attendance at the wild west shows. By 1913, Buffalo Bill Cody realized that the end of the live shows had arrived and that the future lay in motion pictures. He tried to make the transition by producing The Indian Wars, a movie about the massacre of Lakota ghost dancers at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. The movie was filmed on location and used many Lakota actors. He chose Pine Ridge as the location for his first film because the reservation was home to many professional Indian actors with Wild West show experience that he hoped would translate easily to film.

To portray the American military, Cody arranged for the cooperation of the U.S. Army and General Nelson Miles. Miles insisted that the film show the army story of the battle. Unlike some of the Lakota actors, none of the soldiers actually took part in the battle. According to oral tradition, many of the young Sioux men who acted in the film considered the possibility of the replacement of real lead for the filmmaker’s blanks.

Lakota educator Chauncey Yellow Robe, speaking to the Society of American Indians in 1914, said of the film:

“The whole production of the field was misrepresented and yet approved by the government. This is a disgrace and injustice to the Indian race.”

While Cody had hoped for a blockbuster hit, the film flopped badly. Cody had been concerned, perhaps obsessed, with a precision reenactment. While focusing on accuracy, he failed to pay attention to things like story lines and dramatic narrative structures which are critical in motion pictures.

One of the last wild west shows was organized in 1916. The show featured Buffalo Bill and the 101 Ranch Shows. According to the program:

“Col. Wm. F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) actively participates in the military maneuvers as well as in the battle between United States cavalrymen and a band of Indians led by the famous Sioux, Chief Iron Tail, which is a stirring feature of the exhibition…He is accompanied by over a hundred Sioux and other Indians, with their squaws and papooses…”

While the era of the wild west show is over, the Indian stereotypes which they had nourished would live on and be reinforced in the motion pictures which replaced them.

Leave a Reply