The expansion of the American empire westward across the Mississippi River was motivated by greed and supported by God. During the nineteenth century American greed was manifested in an obsession for privately owned land and for gold, silver, and other precious metals. Americans believed that the role of government was to obtain land and mineral rights from the Indian nations that owned them and then give them to entrepreneurs for private exploitation. Many Americans believe that their God has made them a chosen people with dominion over both nature and all pagan nations.

In 1876, American greed focused on the possibility of great wealth in the form of gold in South Dakota’s Black Hills, an area of great historical and spiritual importance to many Indian tribes, including the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and others. Turning a blind eye to U.S. law, international law, and U.S. treaty obligations, the government focused on getting the gold into the hands of non-Indians.

When the Sioux, the tribe declared by the United States to be the owners of the Black Hills, made it clear they did not wish to relinquish this land to the gold seekers, the United States simply declared war on them. The Sioux must relinquish the Black Hills or starve. Congress passed an act which provided:

“hereafter there shall be no appropriation made for the subsistence of the Sioux, unless they first relinquish their rights to the hunting grounds outside the [1868 treaty] reservation, ceded the Black Hills to the United States, and reached some accommodation with the Government that would be calculated to enable them to become self-supporting.”

Any Indian who hunted in the unceded lands was not able to receive any food or supplies. If an Indian went out to hunt, even if starving, it meant losing all benefits for the rest of the year.

The United States then issued an ultimatum to the Sioux: all of the bands were to report to their agency by January 31 or be considered hostile. The ultimatum was intended to result in war for two basic reasons: (1) moving a band in January was difficult, if not impossible, and (2) most of the bands outside of the agency were unable to get word about the ultimatum.

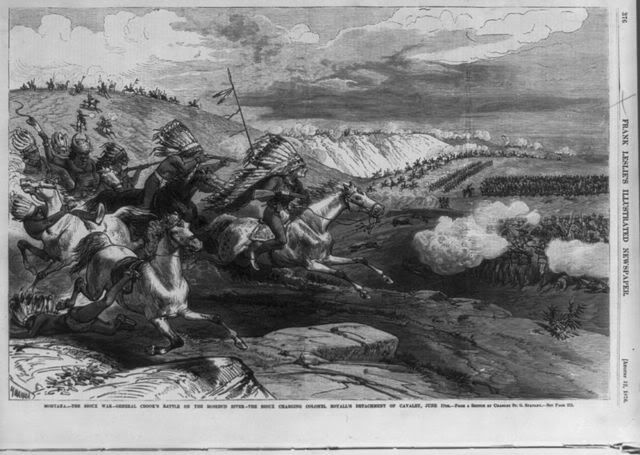

The army then launched a three-pronged pacification campaign against the “hostiles” who had “refused” to come in. While the prong led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer is best known, there was also a campaign from the south led by General George Crook.

Traditional Indian warfare on the Northern Plains, while it involved battles and occasional deaths, was very dissimilar to European warfare. Warfare, according to Sioux writer Charles Eastman, was about courage and honor:

“It was held to develop the quality of manliness and its motive was chivalric or patriotic, but never the desire for territorial aggrandizement or the overthrow of a brother nation.”

The motivation for war was personal gain, not tribal patriotism. Through participation in war an individual gained prestige, honor, and even wealth (as counted in horses.) While it was not uncommon for warriors to kill their enemies in battle, this was not in itself considered to be a particularly noteworthy act of valor. The greatest feat of bravery a warrior (male or female) could perform was to touch the enemy. This was the act of counting coup.

At the headwaters of the Rosebud River in Montana, General Crook’s troops, with 176 Crow and 86 Shoshone allies, encountered an encampment of Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux under the leadership of Crazy Horse and engaged them in a day-long battle. Militarily the battle might be considered a draw as neither side won a decisive victory. Some military historians consider it a strategic defeat for Crook because he was unable to take the offensive and strike a decisive blow at the enemy camp. Chief Runs-the-Enemy said of the battle:

“The general sentiment was that we were victorious in that battle, for the soldiers did not come upon us, but retreated back into Wyoming.”

The Americans sustained casualties of 10 killed and 21 wounded. Crazy Horse later estimated that 39 Lakota were killed and 33 wounded.

From the traditional Indian perspective, there were two particularly important acts of valor in the battle and these two warriors were considered to have gained the greatest war honors.

The Shoshone and Crow shot the horse of Cheyenne Chief Comes in Sight out from under him. As they were closing in to finish him off, Buffalo Calf Robe (aka Calf Trail Woman), the sister of Comes in Sight, rode into the middle of the warriors and saved the life of her brother. Buffalo Calf Robe had ridden into battle that day next to her husband Black Coyote. From the Cheyenne perspective, a woman warrior achieved the highest war honors that day.

One Crow two-spirit (berdache) put on men’s clothes and distinguished himself in battle against the Lakota. For this he was given the name Osh-Tisch which means “Finds Them and Kills Them.” Thus, from the Crow perspective a two-spirit-a person many people today might consider to be a transvestite-won the greatest war honors.

Shown above is an artist’s interpretation of the Battle of the Rosebud.

Leave a Reply