The Navajo Reservation with its tribal headquarters in Window Rock, Arizona, is the largest Indian reservation in the United States. During the 1950s, the Navajo had to deal with an American government which was firmly committed to the destruction of the Indian way of life and to the transfer of any possible reservation wealth to large non-Indian corporations.

Economic Development:

By the 1950s, the American government had returned to the failed Indian policies of the late nineteenth century with a focus on assimilation of the individual Indians into American society and to a transfer of potential wealth on Indian reservations from the Indians to non-Indian corporations.

Congress passed the Navajo-Hopi Long Range Rehabilitation Project in 1950 which appropriated $90 million dollars to be spent on the reservation. Projects under this act included the construction of schools, housing, and hospital; the construction and maintenance of roads; the construction of sewer systems; soil and water conservation; irrigation works; and the provision of electricity. On the Navajo reservation this money was used to prepare Navajo country for private industry, and to give public finance capability to tribal government, so that it could manage the ‘grooming process’ and maintain the Navajo labor force during busts.

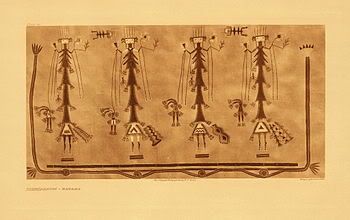

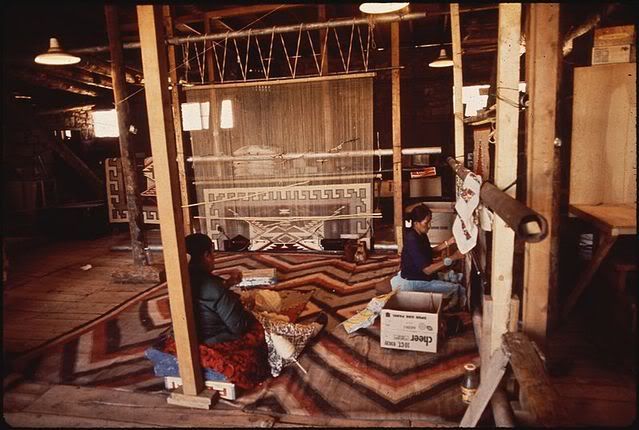

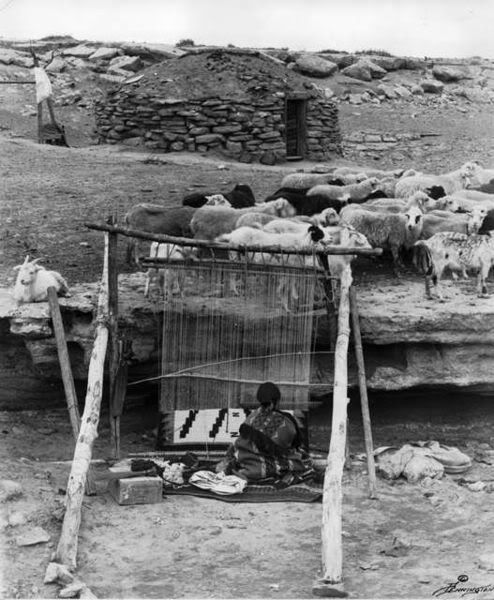

Traditionally, one of the major economic forces on the reservation had been Indian-made handicrafts, particularly Navajo blankets and rugs. In 1950, the Navajo Tribal Council approved the construction of a wool-processing plant at Leupp which would benefit the Navajo weavers.

The sale of Navajo handicraft items was developed by traders. In 1950, non-Indian traders at the Sacred Mountain Trading Post began to seek out active Navajo potters in the area north of Flagstaff. They soon found ten women who brought in a number of examples of their work. The traders began to encourage pottery making among the Navajo and to find markets for it.

In 1956, the Navajo Tribal Council appropriated $300,000 to subsidize companies that were willing to locate on the reservation. While four companies were attracted by the tribal payroll subsidies and other inducements, three closed their facilities as soon as they had exhausted their subsidies. Corporations had little interest in actually helping the Navajo.

Resource Development:

During the 1950s, the intention of the American government was to terminate all Indian reservations, particularly those with timber resources. Fortunately, the Navajo Reservation does not have abundant timber resources and so it was not slated for immediate termination. However, the Unite States sought to transfer other resources on the Navajo reservation-particularly water, uranium, and coal-to non-Indian corporations for development. The Bureau of Indian Affairs worked actively on behalf of non-Indian corporations to develop Navajo resources for the benefit of the corporations, not the Navajo.

In 1952, the Navajo Tribal Council, encouraged by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, approved a mineral extraction agreement with Kerr-McGee Nuclear Corporation. This agreement allowed the company access to uranium deposits near the town of Shiprock. In exchange, the company was to employ 100 Navajo miners who were to work at about 67% of the prevailing non-reservation underground mining wages. In order to increase its profits and reduce its operating costs, the company simply ignored worker safety regulations. The underground mine was supposed to have ventilation, but the ventilation fans did not work. Both the company and the United States Atomic Energy Commission failed to inform the Navajo workers about the known health risks involved in working in uranium mines.

By 1954, the Kerr-McGee Corporation was mining enough uranium from its mines on the Navajo reservation that it built a processing plant for the ore at Shiprock.

Economic development in the arid southwest requires water. While the Supreme Court in the Winters Doctrine had clearly indicated the priority for Indian water rights, most state and federal agencies, including the Bureau of Indian Affairs, simply ignored this ruling. Water rights reemerged in 1953 when the United States petitioned to intervene in Arizona v. California declaring that

“the United States of America asserts that the rights of the use of water claimed on behalf of the Indians and Indian tribes set forth in this petition are prior and superior to the rights to the use of water claimed by the parties to this cause in the Colorado River.”

The states responded angrily to this assertion of Indian water rights. In response to political pressure, the Justice Department recalled the petition and removed the reference to “prior and superior.”

The Navajo responded to the change in language by hiring their own attorney and arguing before the Special Master that this change was clear evidence that the Justice Department was not representing the best interest of Indians and the government is therefore violating its fiduciary responsibility. The court did not accept this argument.

In 1955, the Navajo tribe hired an outside consultant to oversee its oil and gas leases. The tribe also had a study done of potential oil and gas properties on Navajo land. The study recommended that the existing lease arrangements be replaced with partnerships. In response, the tribal council declared a moratorium on new leases.

The following year, the Navajo drew up a contract with the Delhi-Taylor Oil Company to explore and develop five million acres of reservation land. The tribe and the company were to split any profits on a 50-50 basis. While the tribe felt that this joint venture was valid because the Navajo tribe was the owner of the lands, the Secretary of the Interior Fred A. Seaton called it ‘risky,’ probably illegal, and forbade it. The oil industry waged a publicity campaign against the deal. As usual, the government supported non-Indian corporate interests.

In 1956, the Navajo opened up general bidding on 230,000 acres of oil-rich reservation lands in Utah. When the bidding ended, the tribe collected $12 million in lease money and 12.5% of the gross value of any oil produced. Instead of distributing the royalties as per capita payments, the tribe invested the money in education and economic development.

In 1957, Utah Mining and Construction negotiated a contract with the Navajo to allow the company to strip-mine coal just south of the San Juan River. The Arizona Public Service Company agreed to build a coal-fired electric generating station next to the mine.

Removal and Relocation:

As a part of the government’s program to terminate reservations and force Indians to assimilate, the Bureau of Indian Affairs forcibly relocated Indians to urban areas. During this era, many Navajo families were relocated to Los Angeles, San Francisco, Denver, and other cities. Unlike other reservations, however, the Navajo also faced removal to other reservations and removal from public lands which they had traditionally used.

In 1950, resettlement of Navajo families from the Navajo Reservation to the Colorado River Reservation began. Over a two-year time period, 92 families were resettled.

In 1953, the Navajo were removed from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands around Butler wash and tributary areas in Utah. To notify the Navajo herders who had traditionally used these lands, the BLM simply posted notices on sagebrush and dead trees. The notices warned that the BLM was about to impound the Navajo livestock, but the BLM seemed unaware that most Navajo could not read. In the removal process, the Navajo men were handcuffed, their stock herded onto trucks, and their hogans burned. Some people reported that they were whipped and some reported that their livestock was killed.

Some Navajo filed a complaint against the Bureau of Land Management and received $100,000 for lost livestock. In answering the complaint, the BLM could not provide convincing testimony about being aware of problems in legality of how they handled the situation. While the judge ordered further investigation, nothing came from it.

Peyote:

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century a pan-Indian religious movement which would become known as the Native American Church developed on many reservations. In spite of its Christian overtones, Christian missionaries and the government strongly opposed this movement. Since the Native American Church used peyote as a sacrament, the opposition focused on this substance, claiming that it was addictive and thus should be banned. While the Native American Church was popular among many reservation Navajo, opposition to it came from two fronts: traditionals who pointed out that this was not a traditional Navajo religion, and Christians who warned that it was Satanic, evil, and addictive. As a result, the religion was banned on the reservation as well as in the surrounding states.

In 1954, the Navajo Tribal Council held two and a half days of hearings to reconsider its 1940 anti-peyote ordinance. Anthropologists, pharmacologists, and peyotists testified on behalf of the use of peyote. The council took no action on this matter. In 1958, however, the Navajo Nation enacted an ordinance making it an offense to bring peyote onto the reservation. Members of the Native American Church responded by filing suit against the tribe in federal court.

In 1958, in Shiprock, New Mexico on the Navajo reservation, a Native American Church service was raided. Shorty Duncan, William P. Tsosie, and Frank Hann, Jr. were arrested and assessed a fine and a jail penalty under the Navajo tribe’s anti-peyote ordinance.

In 1959, in the Native American Church versus the Navajo Tribal Council, the Court of Appeals ruled that the First Amendment did not bind the Tribal Council. The Navajo Tribal Council had passed an ordinance which made it an offense to use peyote. The ordinance was passed because the Tribal Council did not feel that the use of peyote was a part of traditional Navajo religious practices. The Court felt that the First Amendment applied only to Congress and that it was made applicable to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment. Since the Tribes were not States, the Court ruled, the First Amendment did not apply to them. The court also declared:

“Indian tribes are not states. They have a status higher than that of states. They are subordinate and dependent nations possessed of all power as such only to the extent that they have expressly been required to surrender them by the superior sovereign, the United States.”

Tribal Sovereignty:

Traditionally, the Navajo had never been politically unified. By the 1950s, a time when the United States was attempting to get rid of Indian tribes, the Navajo were in the process of creating a tribal government and expressing themselves as a sovereign entity as described in the U.S. Constitution.

Annie Dodge Wauneka (shown above) became the first woman elected to the Navajo Tribal Council in 1951.

In 1955, the Navajo Tribal Council formally recognized and incorporated the chapter system into tribal government.

In Williams versus Lee, the Supreme Court ruled in 1959 that state courts did not have jurisdiction in a matter involving a non-Indian in Arizona suing a Navajo reservation Indian for goods sold on the reservation. According to the Court:

“To allow the exercise of state jurisdiction here would undermine the authority of the tribal courts over Reservation affairs and hence would infringe on the right of the Indians to govern themselves.”

In 1959, the Navajo Nation formed its own judiciary. The tribal courts, which had been under the direct control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, were now controlled by the tribal council. There was now a trial court with seven judges and an appeals court with three judges. Jurisdiction was limited to civil and domestic problems, and offenses committed by Indians on the reservation in violation of the Navajo Law and Order Code. Law professor Charles Wilkinson writes:

“A foundation of Navajo justice is Navajo common law, similar method but not result to English and American common law, in which the judges develop legal rules that reflect the society’s history, traditions, economy, and natural resources.”

At this time, the Navajo Tribal Council also took control over the Navajo Police from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

I found sight is rich in beauty of landscape and wonder of nature..I guess roots are originated from it..