When Benjamin Harrison became President in 1889, he appointed Thomas Jefferson Morgan as his Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Like most of his predecessors, Morgan had no experience in Indian affairs, little contact with actual Indians, and no understanding of Indian cultures. He was, however, a Baptist minister and an educator with a fervent belief that Christianity held the solution to the “Indian problem.” With regard to his philosophy of Indian education, Morgan wrote: “When we speak of the education of the Indians we mean the comprehensive training and instruction which will convert them into American citizens, put within their reach the blessings which the rest of us enjoy, and enable them to compete successfully with the white man on his own ground and with his own methods. Education is to be the medium through which the rising generation of Indians are to be brought into the fraternal and harmonious relationship with their white fellow-citizens and with them enjoy the sweets of refined homes, the delight of social intercourse, the emoluments of commerce and trade, the advantages of travel, together with the pleasures that come from literature, science, and philosophy, and the solace and stimulus afforded by a true religion.”

Congress passed legislation in 1889 which allowed the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to enforce the school attendance of Indian children by withholding rations and annuities from Indian families whose children were not attending school.

With regard to education, Morgan felt that Indian history should not be taught and that it was important that Indian children acquire a fervent patriotism for the United States. In stressing patriotism, he ordered that all Indian schools celebrate national holidays: Washington’s birthday, Decoration Day, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. Furthermore, he ordered that the American flag be displayed and that the students be taught reverence for the flag as a symbol of American protection and power.

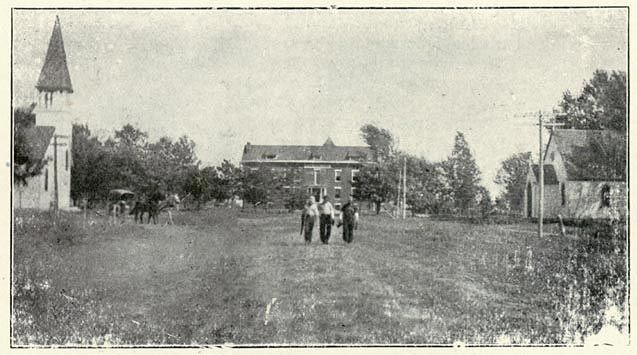

Morgan also felt that for Indians the “school itself should be an illustration of the superiority of the Christian civilization.”

While the United States often turned over the running of Indian schools to missionary societies, Morgan strongly opposed the funding of Catholic schools for Indians. Morgan’s anti-Catholic sentiments were well known and for his term of office he battled with the Bureau of Catholic Missions.

In 1890, Morgan announced that the 8th of February was to be celebrated as Franchise Day. It was on this day that the Dawes Act was signed into law, and the Commissioner felt that this “is worthy of being observed in all Indian schools as the possible turning point in Indian history, the point at which the Indians may strike out from tribal and reservation life and enter American citizenship and nationality.”

Morgan also published a detailed set of rules for Indian schools which stipulated a uniform course of study and the textbooks which were to be used in the schools. The Commissioner prescribed the celebration of United States national holidays as a way of replacing Indian heroes and assimilating Indians. According to the Commissioner: “Education should seek the disintegration of the tribes, and not their segregation. They should be educated, not as Indians, but as Americans.”

Schools were to give Indian students surnames so that as they became property owners it would be easier to fix lines of inheritance. Since most teachers could not pronounce or memorize names in native languages, and they did not understand these names when translated into English, it was not uncommon to give English surnames as well as English first names to the students. There were a number of Indians who were given names such as William Shakespeare, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington.

In 1892, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas Morgan published a pamphlet to centralize Indian education and to unify the curriculum of the Indian Office schools. With regard to the role of art in Indian schools, Morgan felt that art would help improve manual skills. Morgan’s approach to teaching art had been discarded by most public schools in the 1880s. The model for teaching art ignored individual development, skill proficiency, and intellectual progress. American Indian children were taught to draw from a European perspective which did not take into account their indigenous knowledge or environment.

Indian Schools were ordered to celebrate Columbus Day on October 21,1892. Indian students were to pay homage to the so-called “discoverer” of the “New” World. Education professor David Wallace Adams, in his book Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, notes: “Indian students must be made to see that Columbus’s accomplishment was not only a red-letter day in history but also a beneficent development in their own race’s fortunes. Only after Columbus, the myth went, did Indians enter into the stream of history; only after Columbus did Indians begin the slow and painful climb out of the darkness of savagery.”

Leave a Reply