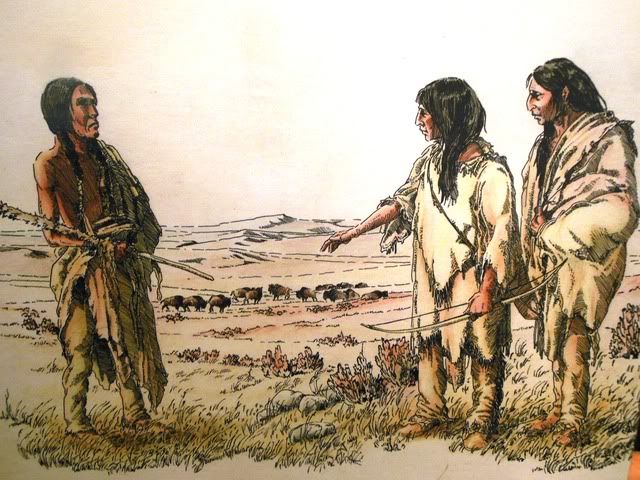

The common stereotype of Plains Indians sees them as horse-mounted buffalo hunters. The reality is, of course, that Plains Indians did not adopt the horse and its equestrian lifestyle until the eighteenth century. There were, however, bison hunting Indian peoples long before the arrival of the horse.

On the grasslands of southern Saskatchewan and Alberta, Canada, archaeologists have found evidence of early bison hunters who specialized in bow hunting which has developed by 200 CE. Aboriginal people began to use the bow and arrow somewhat earlier than this, but they used it as a supplement to the atlatl. Archaeologists Ian Dyck and Richard Morlan, writing in the Handbook of North American Indians, report: “Avonlea people were the first to rely almost exclusively on bows and arrows.”

With regard to the use of the bow and arrow, J. Roderick Vickers, writing in Plains Indians, A.D. 500-1500, reports: “It is hypothesized that this technology diffused from Asia, perhaps through the mountain interior of British Columbia.”

Archaeologists consider Avonlea as a complex, which means that it is a group of artifact types which are found in a chronological sub-division. Avonlea does not, therefore, refer to a specific tribe. There are some who feel that Avonlea is ancestral to the Athapaskan peoples, including Chipewyan, Beaver, and Sarcee.

While archaeologists have not uncovered any Avonlea bows, they have found arrowshafts and a distinctive arrow point. The Avonlea arrow points are small and thin, with tiny side notches. These points were originally found at a site in Saskatchewan and were thus named Avonlea after the site. The fine craftsmanship shown in the Avonlea projectile points suggests that strong social control was exercised in their production. J. Roderick Vickers writes: “Assuming that Avonlea competitive success was partly grounded in their innovative weapon system, there may have been magico-religious sanctions associated with production standards and use of the bow and arrow. That is, they may have been an attempt to prevent the spread of their weapon technology, at least in detail, to others.”

Avonlea first appears along the Upper and Middle parts of the Saskatchewan River basin and during the next 200 years spreads into the Upper Missouri and Yellowstone River basins in present-day Montana. From its beginnings about 200 CE, Avonlea seems to reach its peak about 800 CE and by 1300 CE it has disappeared.

With regard to subsistence, bison seem to have been a major factor in the Avonlea diet. Ian Dyck and Richard Morlan write: “Avonlea hunters were adept at communal hunting methods that allowed them to bring together and dispatch dozens of animals at one time.” Communal hunting included the use of pounds and jumps, such as the buffalo jump at Head-Smashed-In.

One of the ways Indian people hunted buffalo was to drive them over a cliff. Scattered across the Northern Plains are thousands of these buffalo jump sites. Many of them were used only once, while others were used repeatedly. For the buffalo jump, several hundred people (sometimes more than a thousand) would come together. Archaeologist Jack Brink, in Imagining Head-Smashed-In: Aboriginal Buffalo Hunting on the Northern Plains, writes: “Not only were buffalo jumps an extraordinary amount of work; they were the culmination of thousands of years of shared and passed-on tribal knowledge of the environment, the lay of the land, and the behavior and biology of the buffalo.”

The buffalo pound was a way of harvesting large numbers of bison in a similar fashion to the buffalo jump. However, the final kill location was not a cliff, but rather a pound or corral made of wood. Pounds were located in the lightly wooded areas that surround portions of the Great Plains. Here the hunters could find enough wood to build the pound. Using techniques similar to those used in the buffalo jump, the herd would be lured over many miles and then driven into the pound where they would be killed with bows and arrows and spears as they milled around.

In addition to hunting bison, the data from the Avonlea archaeological sites show that they also hunted pronghorn antelope, deer, beaver, river otter, hares, and waterfowl. The Avonlea people also used weir fish traps during the spring spawning runs.

Like the later horse-mounted Plains Indians, the Avonlea people used tipis. Archaeologists have found tipi rings associated with Avonlea material culture at several sites. The tipi coverings were held down with rocks and thus the archaeological remains are simply a ring of stones, sometimes with a hearth inside. For Indian people using dogs rather than horses to carry loads, the tipis were smaller than those used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Avonlea people also made and used pottery. Several pottery types—net-impressed, parallel-grooved, and plain—have been found at Avonlea sites. Pottery vessels usually have a conoidal or “coconut” form.

There are a number of hypotheses about what happened to the Avonlea people. One hypothesis sees them having migrated south where they would later emerge as the Navajo and Apache people. Another sees them as staying on the Northern Plains where they contributed to the Old Woman’s phase, which is associated with the North Piegan, Blood, and Gros Ventre. Some feel that Avonlea may have contributed to the Tobacco Plains phase of the Kootenay Valley of the Rocky Mountains. There is also speculation that they were involved in the formation of the village cultures of the Middle Missouri tradition. Ian Dyck and Richard Morlan write: “It is, of course, possible that the fate of the Avonlea culture took more than one twist.”

J. Roderick Vickers summarizes Avonlea this way: “In the end, archaeologists must plead ignorance in understanding the appearance of Avonlea on the Northern Plains. It seems we can state that Avonlea is a culture of the western Saskatchewan River basin and that it expanded southward into central Montana, westward over the Rocky Mountains, and northeastward into the forest margins.”

Leave a Reply