The Sonoran Desert which stretches across part of the present-day American state of Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora is an area of very hot summers (high temperatures may reach 120° F) and relatively little rain. It was here that a culture called Hohokam by archaeologists flourished from 300 BCE until about 1400 CE. The Hohokam were village agriculturalists who developed a sophisticated canal system to bring water to their crops in this desert environment.

The descendants of the Hohokam are the O’odham, a name which means “we, the people”. However, ethnologist Bernard Fontana, in his book Of Earth and Little Rain: The Papago Indians, writes:

“It also means Those Who Emerged from the Earth. It means sand, or dry earth, endowed with human quality.”

The O’odham are divided into four basic groups:

- Akimel O’odham in Central Arizona. These people are also called Pima. The name Pima comes from the Spanish corruption of the phrase Pi-nyi-match which means “I don’t know.” This was given as the answer to the questions asked by the first Spanish explorers and the Spanish, in turn, thought that this was their tribal name.

- Tohono O’odham in southern Arizona and northern Sonora. The Tohono O’odham are also called Papago which is derived from the Akimel O’odham name Papahvi-o-tan which means “bean people.”

- Pima Bajo in Mexico.

- Sobaipuri occupied the San Pedro River valley from Fairbank, Arizona, north to the Gila River junction, and the Santa Cruz River valley north to Picacho. The Sobaipuri were driven out by the Apache and the Spanish and intermingled with the other O’odham groups. The term Sobaípuri cannot be directly translated. Some people feel that Sobaípuri is a combination of the names Soba and Jípuri. This may indicate that two groups came together to become a single group.

Farming

Prior to the coming of the Europeans, the O’odham viewed land, water, and food as something which was owned in common by the village. The principal crops included corn, beans, squash, and cotton. The Akimel O’odham were able to start planting early and often obtained two crops during the summer which were harvested in July and October. The Tohono O’odham usually had only one harvest.

Gathering

Prior to the coming of the Europeans, about 75% of the food consumed by the Tohono O’odham and 40% of the food consumed by the Akimel O’odham came from wild plants. These included seeds from the mesquite, ironwood, palo verde, amaranth, saltbush, lambsquarter, mustard, horsebean, and squash. They also used acorns and other wild nuts. Over 50 edible plants were used.

In gathering the fruit of the saguaro cactus, each household had its customary gathering grounds. It was important to ask permission for gathering in someone else’s area. Saguaros grow up to 50 feet high and the fruit are at the top. The fruit are picked by using a long stick – often two saguaro ribs tied together – to push the fruit off. The picking is usually done by two people: one uses the pole to pick the fruit and the other gathers it when it hits the ground.

The saguaro is picked in July and the fruit is cooked immediately. Cooking is done in a pot over an open fire. The pulp is strained and the juice is used as the base for syrup. According to Bernice Johnston, in her book Speaking of Indians With An Accent on the Southwest:

“It makes a wonderful topping for ice cream or hot cakes.”

Villages

One of the features of O’odham villages was a round building in which no one lived. East of this building was an open-roofed sunshade. Under the shade or a few feet to the east was a fireplace. It was here that the nightly meetings took place. According to Donald Bahr, in an entry in the Handbook of North American Indians:

“The meeting place had to be within shouting distance of the farthest family house, for announcements were made from it in that manner.”

The round public building was called the “smoking house” (“smoking” was an expression for “to have a meeting”) or the “rain house.” This building could accommodate up to 80 people and functioned as both a meeting hall and a ceremonial facility. Since the village leader was responsible for the upkeep of this building, it was usually located near his compound.

Government

The Pimería Alta was made up of a number of small nations whose primary concerns were local rather than regional or tribal. According to ethnologist Bernard Fontana, in his book Of Earth and Little Rain: The Papago Indians:

“Never were all the O’odham of the Pimería Alta allied under a single leader, nor were they ever bound together in a single cause.”

Government operated primarily at the village level. The civil leader of the village presided over community meetings. To call the meetings, the leader would start a fire in the round house or big house and then he would climb to the roof to shout to summon the other men of the village. The civil leader also functioned as a religious leader.

The actual governing authority was vested in the council of all of the mature males in the village. This group often met each night and made all decisions regarding the community, including the dates for ceremonies, intervillage games, farming, hunting, and warfare. According to Genieve De Hoyos , in her book Mobility Orientation and Mobility Skills of Youth in an Institutionally Dislocated Group: The Pima Indian:

“Every decision in the village was made by the men of the tribe meeting in council.”

While all adult males would attend the council meetings, only those who had been through the purification of the sacred journey to the Gulf of California to get salt and those who had been through the purification ceremony required for those who had killed an enemy were allowed to take part in the actual deliberations. Action was taken not by majority vote, but by consensus.

In addition to the civil leader, the villages had two other important leaders: the war leader who took over in time of war, and the hunt leader. All of the leadership positions involved some ritual responsibility. The war leader, for example, had to perform ceremonies that would take away the enemy’s power.

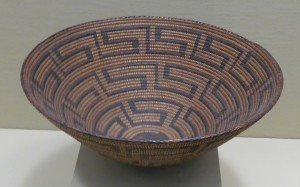

Baskets

For many tourists visiting the Southwest, American Indian curios—pottery, baskets, blankets, carvings—are treasured mementos. Arizona State Museum Assistant Curator Andrew Higgins, in article in American Indian Art, writes:

“In the early 1900s, a tourist industry, spawned by railroad and automobile travel, and a nationwide basketry craze provided further impetus for Indian women to expand their basketry trade.”

In an essay on basketry in Harmony by Hand: Art of the Southwest Indians, Jerold Collings writes:

“In the Southwest, native Americans have been producing baskets in a variety of forms and with considerable technical diversity for at least the past eight thousand years. Rigid and semirigid containers, mats, and bags—all played an important role in their early attempts to cope with a strikingly beautiful but often harsh environment.”

In her book The Ranchería, Ute, and Southern Paiute Peoples: Indians of the American Southwest, anthropologist Bertha Dutton writes:

“Pima women have long been noted for their beautifully woven and artistically decorated basketry.”

It is estimated that six out of ten women were basket weavers at one time. The number of weavers has diminished since the establishment of the reservations as this is a time-consuming task.

One of the distinctive women’s artifacts is the burden basket: a triangular webbed frame which was used for holding firewood, grasses, corn, wild food, and water jars. According to oral traditions, these baskets walked by themselves until Coyote laughed at seeing them in motion. Then they became the women’s burden. Using the burden baskets, Tohono O’odham women would often carry burdens weighing up to 100 pounds.

In addition to the burden baskets, the O’odham peoples make a variety of other kinds of baskets. This includes large grain storage baskets which are so large that the weaver has to stand inside to weave them. These large baskets can hold as much as 50 bushels. The baskets are made from a variety of plants: cattails, willow, sotol, bear grass, martynia, and yucca.

The most common baskets are relatively shallow bowls. In addition, some basketry jars are made for the tourist trade. The designs which decorate the basketry are generally geometric or symbolic. The weavers do not draw the designs prior to weaving, but carry them in their minds. Some of the common symbolic designs include the squash blossom and the butterfly wings.

According to a display at the Portland Art Museum:

“Pima baskets are traditionally coiled using willow rods as a foundation with willow and devil’s claw for the design. Bowls with widely flaring walls are the most common shape and they are frequently decorated with interlocking and fret designs.”

Shown above is a Pima basket which was made about 1900.

Shown above is a Pima basket which was made about 1900.

With regard to the maze designs which are often used in Pima baskets, Arizona State Museum Assistant Curator Andrew Higgins, in an article in American Indian Art, writes:

“Humans have long appreciated maze designs, and both the Pima and Tohono O’odham people feel that this image embodies one’s journey through life. The Pima were likely the first to use this design on basketry, and the Tohono O’odham quickly followed.”

Leave a Reply