As a Christian nation, the United States has never been comfortable with the idea that American Indians might have their own non-Christian religions or that Indian spiritual leaders could provide role-models for other Indians. Under the European notion of the Discovery Doctrine, the United States felt that it had a legal right to rule over non-Christian nations and to convert them to Christianity.

In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant instituted a Peace Policy in which Indian Reservations were assigned to missionaries from 13 Christian denominations. These missionaries were given the administrative powers over the reservation, which included distribution of goods, education, health care, and law enforcement. Catholic historian James White, in an article in Chronicles of Oklahoma, reports:

“Under the terms of the Peace Policy, a single religious group had a franchise over the evangelizing efforts on each reservation.”

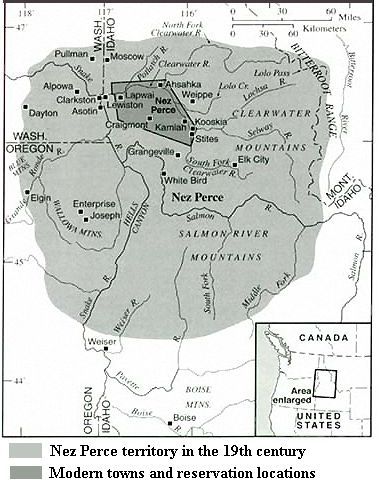

Many reservations become theocracies in which only one religion was allowed. On a number of reservations, such as the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho, Catholic priests were banned from the reservation. Indians who did not convert to the reservation’s Christian religion could be denied services, jailed, or banned from the reservation.

In the 1850s, a prophet had emerged among the Wanapan, a Sahaptian-speaking people living in the Priest Rapids area of present-day Washington state. Like many other American Indian prophets, Smohalla, a hunch-back who had been born about 1815, had visited the Spirit World and had returned with a message for his people. Carl Waldman, in his book Who Was Who in Native American History: Indians and Non-Indians From Early Contacts Through 1900, writes:

“Smohalla’s message was of a resurgence of the aboriginal way of life, free from white influences, such as alcohol and agriculture.”

Since his revelations came to him through dreams, the Americans soon dubbed Smohalla’s religious movement as The Dreamers. His teachings upset the Christian missionaries and government officials in the territory. He was jailed on several occasions for preaching his Indian message.

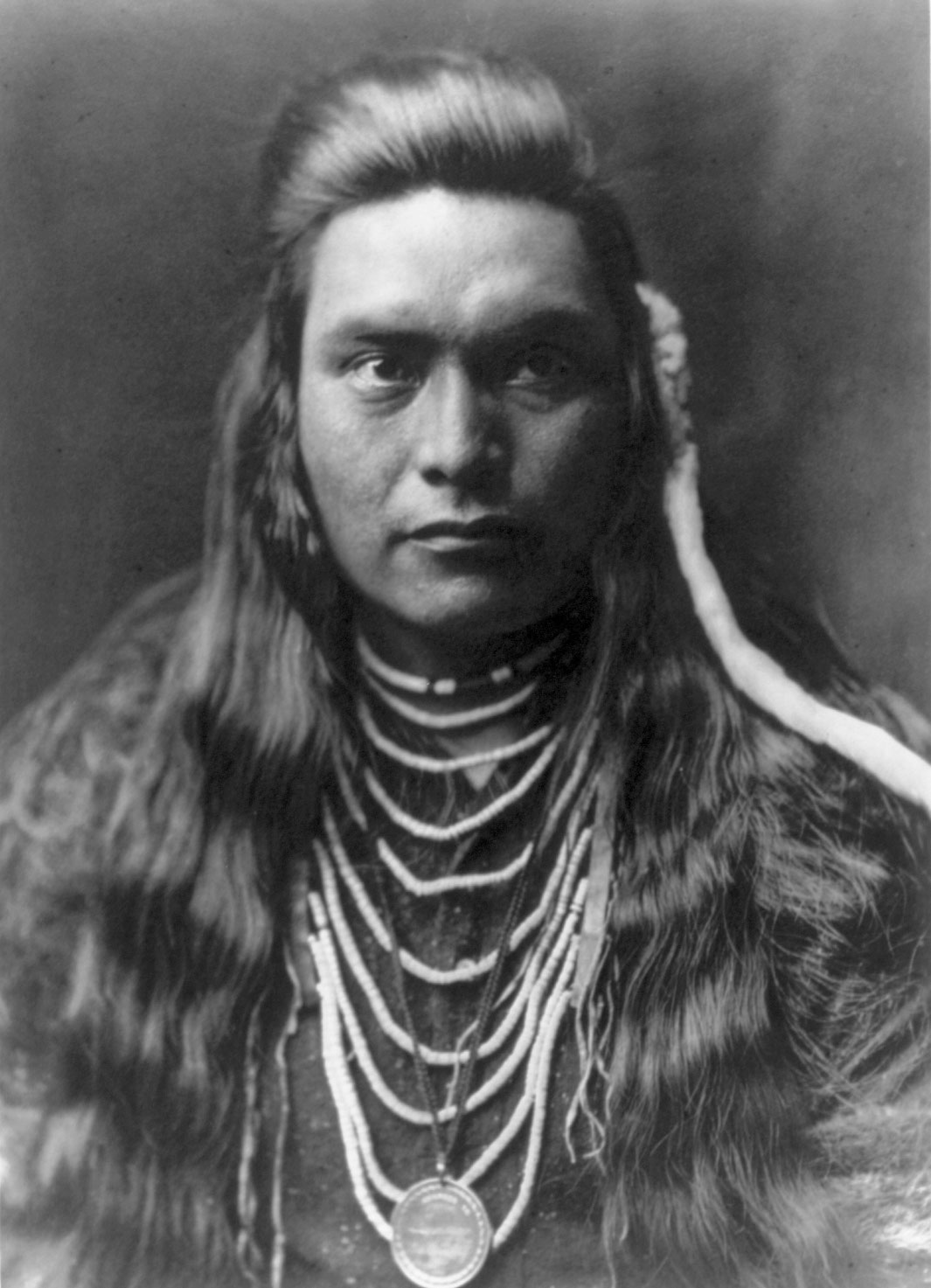

Smohalla’s teachings spread to other Sahaptian-speaking tribes, particularly the Nez Perce. One of the early converts was Old Chief Joseph, a former Christian.

In 1875, the Tacoma Herald called Smohalla “the most dangerous savage in the country”. Smohalla did not advocate violence, but simply pointed out that the Americans were destroying the earth. The Indian superintendent for the territory felt that Smohalla’s religious movement had to be suppressed and was incredulous that “their model of a man is an Indian.” In their book Renegade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, Clifford Trafzer and Richard Scheuerman report:

“The Wanapum Prophet did not fit the white man’s image of a great leader, for he was considered ‘to be a rather undersized Indian with a form inclining toward obesity.’ Added to this, the ‘peculiar’ holy man was born with a hunchback and a large, oversized head. But what he lacked in appearance, he made up for with his ability as an orator who could hold his listeners ‘spellbound’ with his ‘magic manner.’”

The Christian Nez Perce under the leadership of James Reuben in Idaho, who had taken their Presbyterianism to extreme piety, viewed Smohalla as a threat and someone who had to be stopped. According to Kent Nerburn, in his book Chief Joseph and the Flight of the Nez Perce: The Untold Story of an American Tragedy:

“To them, Smohalla was the purveyor of dangerous falsehoods. His pernicious brand of belief was harmful to their people and threatened to ensnare those among them who were not strong in their Christian faith.”

In 1875, a five-member American commission met with Joseph (the Younger) and other non-treaty Nez Perce leaders to discuss the sale of the Wallowa Valley. Joseph made it clear that his people had no intention of selling. The commission reported that Joseph’s band was under the influence of Smohalla’s Dreamers and recommended that the leaders of this religious movement be exiled to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Aubrey Haines, in The Battle of the Big Hole: The Story of the Landmark Battle of the 1877 Nez Perce War, reports on their recommendation:

“If the non-treaty Nez Perces did not suppress the Dreamer religion and peacefully settle on the reservation within a reasonable time, military force would be used.”

To suppress the Dreamer religious movement and to force the non-treaty Nez Perce to move to the Idaho reservation where they could be forcibly converted to Christianity, the United States government called upon General O.O. Howard. General O.O. Howard acknowledged that the American settlers and the Nez Perce were unable to live together peacefully in the Wallowa Valley and the obvious solution was for the Nez Perce to leave their homeland and settle with the Christian, farming Nez Perce in Idaho.

General Howard was called America’s Christian general by the American Press and among Indian people he was known as the Praying General. In 1874, General Howard had been assigned to the Department of the Columbia (Oregon, Washington, Idaho).

In 1877, General Howard met with the non-treaty Nez Perce to persuade them to move to the Idaho reservation. Howard felt that it was his duty as an American officer and a Christian to force the non-treaty bands into becoming Christian. He opened the council by having a Christian Nez Perce speak a Christian prayer. In this way, he demonstrated to the Dreamers that not only was Christianity the only religion that he recognized, but that the Americans felt it was superior to any Native religions.

Among those at the council were Joseph, Ollokot, Young Chief, White Bird, Toohoolhoolzote, Husishusis Kute (Little Baldhead), Taktsoulkt Ilppilp (Red Echo) and Looking Glass. The Nez Perce chiefs selected Toohoolhoolzote to speak for them. Regarding Toohoolhoolzote, Kent Nerburn writes:

“He was a man of powerful medicine and a committed follower of Smohalla’s teachings about the living spirit of the earth.”

The Americans, concerned about the Dreamers, made promises that the government would not interfere with their religion. Toohoolhoolzote continued to tell the Americans that his people had never given up their land and that they were trifling with the laws of the earth. General Howard finally grabbed Toohoolhoolzote and took him to the guardhouse where he was placed under arrest. General Howard would later write:

“We listened to the oft repeated Dream nonsense with no impatience, till finally he accused us of speaking untruthfully about the chieftainship of the earth.”

General Howard issued an ultimatum to the Nez Perce, ordering them to the Idaho reservation in just 30 days time and at a season when the rivers were high and difficult to ford. While the desire to open Nez Perce land up to American settlers played an important role in this decision, military fear of a Native American religious movement was more important. This marked the start of the Nez Perce War.

While the American army defeated the Nez Perce at the Battle of the Big Hole in Montana, Smohalla’s religion continued and can still be found on several reservations in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. When Smohalla died in 1895, Dreamer leadership passed to his son Yo-Yonan.

Leave a Reply