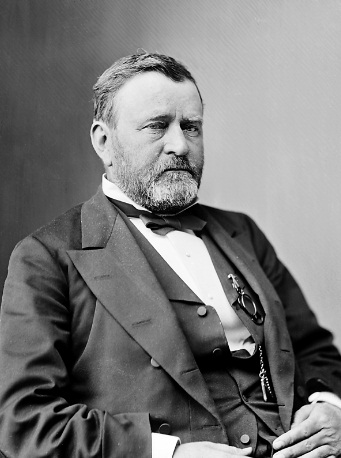

When Ulysses S. Grant assumed the Presidency, he inherited a major problem with regard to the administration of the Indian reservations. The Indian Service was notoriously corrupt and his solution was to create faith-based reservations: that is, to turn the administration of the nation’s Indian reservations over to Christian, primarily Protestant, missionary groups. The missionaries, working on behalf of the United States government, were to help the Indians on the road to civilization which required them to become English-speaking Christian farmers.

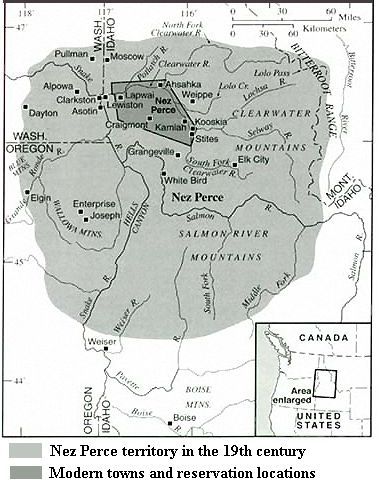

In 1871, the Nez Perce reservation in Idaho was first given to the Catholics, but due to Presbyterian protests it was then given to the Presbyterians. Under this administration, the Presbyterian missionaries and teachers deliberately made the Indians ashamed of their own culture, language, history, and traditions. Old ways were not only frowned upon and ridiculed, they were also prohibited.

At this time, the Nez Perce were divided into two main factions: the reservation group which was primarily Christian (mostly Presbyterian), pro-American, and willing to accept European customs, and the off-reservation group which had adopted an anti-government, anti-treaty, anti-Christian, and anti-acculturational stance. The off-reservation group was involved in the 1877 Nez Perce War.

The new Indian agent, determined to continue and strengthen the Presbyterian influence on the reservations, ordered the Methodist missionary off the reservation and refused to allow the Catholics to build a mission.

The missionaries on the reservation opposed those things they viewed as associated with Nez Perce heathenism: polygyny, gambling, shamanism, guardian spirits, and any Indian ceremony that including drumming, singing or chanting, and dancing. They also condemned long hair on men, aboriginal clothing, and horses, as all of these had been a part of the traditional Nez Perce way of life. They also strongly opposed the Catholics, who had not been a part of the traditional lifestyle, but who were seen by the Presbyterians as heathens or pagans.

In 1873, the United States government built a church for the Presbyterian mission at Kamiah, Idaho on the Nez Perce reservation.

In 1884, the United States formally outlawed “pagan” Indian ceremonies and any form of promoting these ceremonies. Indians who were found guilty of participating in traditional religious ceremonies were to be imprisoned for 30 days. This was seen as an important step in the destruction of the Indian way of life.

As the United States government legislated against traditional Native American religions, the Presbyterian missionaries on the Nez Perce Reservation were scandalized at what they viewed as the pagan interpretations of patriotic holidays. During holidays, such as the Fourth of July, many of the Nez Perce would engage in such heathen practices as horse-racing, war dancing, and open sexuality. In order to counter these “pagan” activities, the missionaries decided to sponsor a picnic to provide a Christian alternative during the holidays.

In 1885, the missionaries among the Nez Perce organized the second annual Kamiah picnic as a way of uniting the Nez Perce and countering paganism. The peace of the picnic, however, was interrupted by gunfire as tribal police under the leadership of Tom Hill attempted to make an arrest. Two men were killed. Tom Hill was later charged with murder, but the jury rendered a verdict of justifiable homicide.

By 1888, all of the Nez Perce Presbyterian churches were under the control of native preachers. Non-Indian missionaries assisted in an advisory capacity.

In spite of picnics and Native preachers, the old ways refused to die. In 1891, as a result of the controversy over the blending of pagan and Christian elements in patriotic celebrations, such as the Fourth of July, the “heathen” Nez Perce were expelled from the agency grounds. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered that the race grounds be fenced and forbid all heathenism and immorality on the school grounds. Later missionary writers would report that this simply removed the heathens from any ameliorating Christian influences. From a Christian missionary viewpoint this meant that the heathen celebrations became more “evil.” Presbyterian missionary Kate McBeth, who was on the reservation at the time, wrote:

“That Fourth of July the camp was made just outside the school ground, half a mile away, and heathenism still raged.”

She went on to say:

“Renegade Indians from almost every tribe on the coast came, delighting to introduce new immoral plays into the Nez Perce camp. Oh! The vileness of it all!”

In 1897, during the ten-day Fourth of July celebration, the Nez Perce broke into two factions: Christian and heathen. Two separate camps were established. Presbyterian missionary Kate McBeth wrote:

“Those who went into the heathen camp were to be considered suspended members until such time as they chose to show sorrow for their acts and confess their sins.”

Word spread among the Christian camp that the heathens were going to lead a parade through the camp. Seven Christian Nez Perce under the leadership of Edward Reboin blocked the road. When the heathen procession led by James Reuben got to them they were stopped. After an exchange of angry words, the procession turned back.

Another Presbyterian missionary wrote:

“In and out of that heathen camp we went and saw all the devilish glamour and savage gorgeousness that covered every kind of wickedness that human mind can invent.”

During the twentieth century, the division between the heathens and the Christians on the reservation remained, but the open conflicts between the two groups became more subtle, often reflected in the political arena.

Leave a Reply