For thousands of years, American Indians used the asphalt from the tar seeps of Rancho La Brea in what is now Los Angeles, California, for many different things. The displays at the La Brea Tar Pits Museum show many of the Native uses of the tar and display some of the artifacts which archaeologists have recovered from the site.

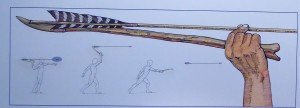

The illustration above shows an atlatl, the American Indian weapon that was used prior to the introduction of the bow and arrow.

Throughout much of Indian history, the primary hunting tool has been the stone-tipped spear. Archaeologist Thomas Wilson, in his 1897 book Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times, reports:

“A spear is a long, pointed weapon, held in the hand, used in war and hunting, more by thrusting than throwing.”

Hollywood movies and television programs (even those of the “educational” variety) usually depict the spear as being thrown, while in fact it was not a very efficient weapon when thrown. To overcome the inefficiency of the spear, Indian people used the atlatl or spear thrower. The atlatl is a wooden shaft with a hook at one end and a handle at the other. The butt of the spear is engaged by the hook. Grasping the handle and steadying the spear shaft with the fingers, the spear can be hurled with great force. Archaeologist L.S. Cressman, in his book The Sandal and the Cave: The Indians of Oregon, notes:

“Thus the atlatl was in principle an extension of the arm and, by the added leverage, gave much greater power to the thrust of the spear.”

Anthropologist Colin Taylor, in his book Native American Weapons, reports:

“the forward momentum was markedly increased by attaching a stone weight to the main body of the atlatl.”

With this arrangement, the spear can be thrown with greater force and for longer distances than if done by arm and hand alone. It is estimated that the atlatl dart has an impact over 150 times as intense as that of a hand-thrown spear.

The atlatl is effective and accurate at ranges up to 150 meters. One of the secrets to the distance and accuracy of the atlatl is found in the use of a light, flexible spear shaft. During the throw, the spear shaft acts like a spring in that it bends and stores energy. The shaft then straightens out as it pushes away from the atlatl, getting more energy in a spring-like effect.

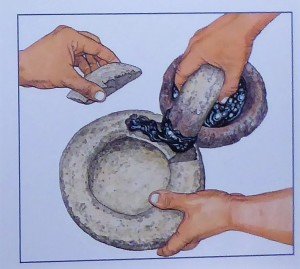

The illustration above shows asphalt being used to repair a broken steatite bowl.

The asphalt was used as a form of waterproofing in making baskets which could hold water. Pebbles would be dipped in the hot asphalt and then used to spread the tar on the basketry.

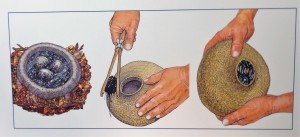

Shown above is a fragment of tarred basketry which dates to the Late Prehistoric Period.

Shown above are some tarring pebbles which date to the Late Prehistoric Period.

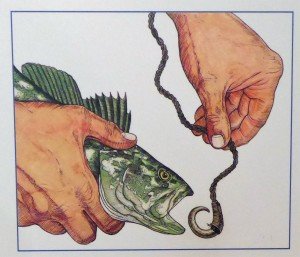

The asphalt was also used on fishhooks.

Shown above is a bone fishhook which has been treated with tar.

Shown above is the 9,000 years old leg bone of La Brea Woman.

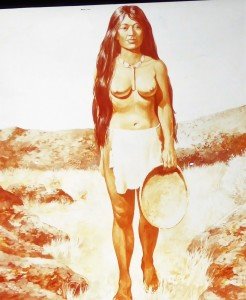

Shown above is what La Brea Woman probably looked like.

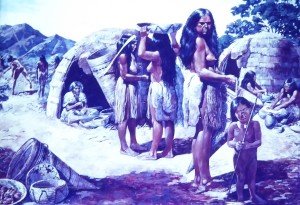

Shown above is a typical village just prior to Spanish contact.

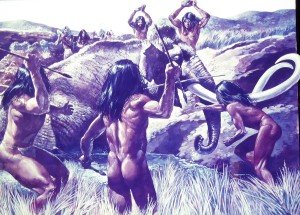

Shown above is a hunting scene.

Artifacts from Rancho La Brea

Shown below are some of the Indian artifacts recovered at the Rancho La Brea site.

The wooden spear tip shown above is 4,450 years old.

Migration to North America

During the last Ice Age, sea levels were more than 300 feet lower than today and there was a land bridge connecting North America and Asia.

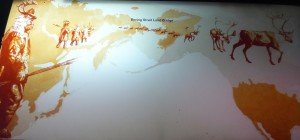

The mural shown above presents one hypothesis about how people migrated from Mongolia to North America across the Bering Strait Land Bridge.

According to the Museum display:

“It seems certain that Mongolian immigrants crossed the Bering ‘land bridge’ but, as yet, there is no conclusive evidence about when they came or what they hunted. This mural presents one of the current theories which suggest that they followed herds of animals to the new world. These first Americans were apparently confined to Alaska until about 30,000 years ago when the continental glaciers temporarily receded to open the way for colonization of the rest of the Western Hemisphere. With the passage of time, they separated into different tribes and developed different languages.”

It should be pointed out that many archaeologists disagree with this scenario and the current archaeological record shows that American Indians were living in North America south of Alaska before the continental glaciers receded. While the inland migration hypothesis was popular several decades ago, today archaeologists tend to view coastal migration as more feasible. In an article in American Archaeology, Tom Koppel writes:

“Archaeologists today increasingly favor the Pacific coast migration model as the most likely explanation for the initial peopling of our hemisphere. This hypothesizes that maritime people from northeast Asia skirted the ice that blanketed Alaska and Canada, using a chain of ice-free offshore refugia as stepping stones. They would have populated the northern Pacific coast some 15,000 to 16,000 years ago, or even earlier, with some spreading inland once they reached the unglaciated North America at Washington State.”

Leave a Reply