In 1923 Deskaheh, a Cayuga chief from the Six Nations Reserve in Canada, traveled to Geneva, Switzerland. For more than a year he attempted to present his people’s case to the League of Nations so that the League of Six Nations could receive international recognition as a sovereign state. His mission failed and he returned home without having been able to speak to the League of Nations. Deskaheh’s journey to Switzerland marks the beginning of many attempts by Indian nations in the United States and Canada to bring their concerns to an international forum.

Following World War II, many of the nations of the world came together to form the United Nations to serve as a forum for international relations. Indian nations as colonial entities were not viewed as sovereign nations as thus were not a part of the United Nations when it was formed.

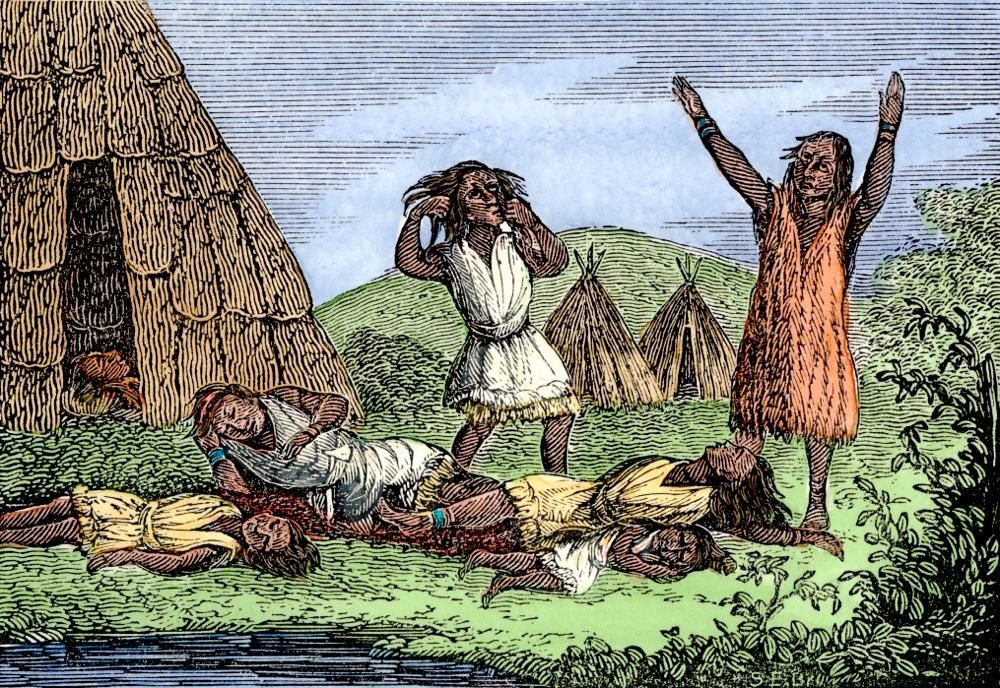

In 1948 the United Nations classified genocide as a crime against humanity. Genocide is identified as an activity against a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group which includes one or more of the following: (1) killing members of the group, (2) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group, (3) inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction, (4) imposing measures to prevent births within the group, and (5) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. Many Indian people realized that the actions of the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries can be viewed as genocide under this definition.

In 1977 the United Nations gave the International Indian Treaty Council status as a Non-Governmental Organization. Several Indian leaders addressed a United Nations conference in Geneva. However, the demands of Indian leaders for international recognition of their sovereign nationhood were unheeded. The conference had no effect on the legal status of Indian tribes in the United States or on their treaties.

The United Nations adopted “Convention On the Rights of the Child” in 1989. This act states that indigenous children “have the right to enjoy their own culture and to practice their own religion and language.” Two nations – the United States and Somalia – did not sign the covenant.

On Human Rights Day in 1992, several indigenous leaders, including Native American leaders, addressed the United Nations as a part of the opening ceremonies of the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People.

Onondaga chief Oren Lyons reminded the United Nations: “Our lands were declared vacant by papal bulls. You created laws to justify the pillaging of our lands. We were systematically stripped of our resources, religions, and dignity.” He goes on to say: “Yet we survive. I stand before you as a manifestation of the spirit of our people and our will to survive. The wolf, our spiritual brother, stands beside us, and we are alike in the Western mind: hated, admired, and still a mystery to you. And still undefeated.”

Thomas Banyacya, a Hopi elder from Arizona, told the United Nations that “we still have our ancient sacred stone tablets and spiritual religious societies which are the foundations of the Hopi way of life,” and “if we humans do not wake up to the warnings, the great purification will come to destroy this world just as the previous worlds were destroyed.”

In 2006 the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues called upon the Catholic Pope to revoke and renounce the fifteenth century papal bulls which are the foundation for the Discovery Doctrine. According to Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation: “These bulls provide the foundation for the theft of indigenous lands throughout the world that continues up to this day. These bulls subjugated innocent and unsuspecting Native peoples and subjected them to more than 500 years of slavery, genocide, and a less than human identity.”

Steven Newcomb (Shawnee/Lenape), the Indigenous Law Coordinator at Kumeyaay Community College, writes: “American Indian nations never freely consented to be bound by or to abide by the ideas historically known as the international law of Christendom.” He goes on to say “The principle of Christian discovery and its accompanying principle of Christian dominion are the illegitimate foundation concepts of U.S. federal Indian law and policy.”

A 2005 report to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights found that Indian prisoners in the United States were facing restrictions on their spiritual practices. These restrictions included English-only mandates on ceremonies, such as the sweatlodge, and unrealistic time limits on ceremonies which did not allow them to be concluded in native fashion. According to the report, prison chaplains, who are usually trained as Christian ministers, were required to oversee traditional Native American ceremonies.

In 2005 the United Nations committee on racial discrimination asked the United States to respond to the Western Shoshone appeal for intervention regarding the attack on their spiritual and cultural areas by the United States and mining corporations. The United Nations asked the United States why Western Shoshone sacred land and treaty rights were not being honored. The U.S. failed to respond to a list of 10 questions from the United Nations regarding this matter.

In 2005 a formal human rights complaint against the United States was submitted to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The complaint stemmed from methyl-mercury contamination of subsistence fish caused by gold mines which were abandoned following the mid-nineteenth century gold rush in California and by the dumping of contaminates by the U.S. military in Alaska. These actions, according to the complaint, have impacted the Pit River tribe in California and the Yupik in Alaska.

In California, hundreds of tons of mercury from the abandoned gold mines have resulted in toxic levels of mercury in fish. For California Indians, these fish have both a food value and a spiritual value. In Alaska, the occurrence of cancer among Alaska Natives has been rising since 1990 at a rate 30% higher than for the general population.

Evidence was also included in the complaint that the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Energy, and other federal and state agencies, frequently dismiss links with contaminants as ‘anecdotal’ or blame the life-styles of those who are suffering from health problems.

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in 2006 discussed a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Article 3 states: “All indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development.” Three nations-the United States, Canada, and Australia-argued that this statement was in violation of international human rights law.

In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly voted to adopt the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration is a nonbinding agreement that formally established the individual and collective rights of indigenous people. The United States and Canada were among the four nations that vote against the Declaration. Some observers of indigenous rights feel that this was most significant development in international human rights law in decades.

As Indian nations become more frustrated with their ability to obtain fairness and understanding in the political process-Congress and the state legislatures-and in the legal process-the courts-they are turning more to international organizations, such as the United Nations and the Organization of American States, to help bring pressure to resolve issues of concern to them.

Leave a Reply