( – promoted by navajo)

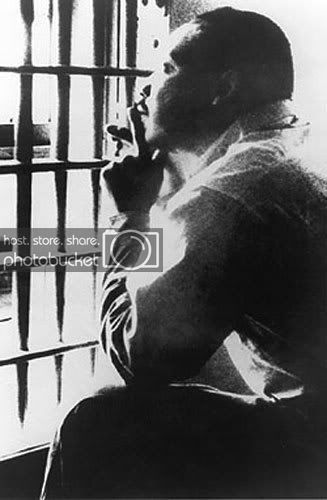

On some positions a coward has asked the question is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right. – Martin Luther King Jr., November 1967

On some positions a coward has asked the question is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe nor politic nor popular but he must take it because conscience tells him it is right. – Martin Luther King Jr., November 1967

A few days ago, coincidentally on Martin Luther King Jr.’s real birthday, I was at a gathering of middling size where I only knew two people. While I sipped my club soda and nearly nodded off listening to someone buzz on and on about football, a conversation cluster within eavesdropping distance took up the subject of reservation casinos. I live in California and four Indian gaming referenda will appear on the ballot February 5, so a discussion of the topic was not a surprise. I’ve always had an (apparently inborn) ability to tune into conversations across a room while blocking out those in front of me, and my interest was piqued because whoever was explaining the gaming proposals seemed to know quite a bit about the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that led to these measures being put before the voters. Then I heard it. Somebody said, “It’s the redskins’ revenge.”

For the first time, I looked over that way, and all five people in the group were gently laughing or smiling or nodding assent.

I don’t think he meant it maliciously. Quite possibly he even thought he was being supportive. It’s doubtful he would have said “nigger” or “wetback” or “chink,” since there were African Americans, Asian Americans and Latinos in the room. But no obvious Indians. Because I don’t wear feathers, mocassins or a loincloth and can pass for white, he apparently felt unconstrained in making what I’m sure he thought was a harmless little joke. Maybe even a pro-Indian joke. I could have walked over and explained how infuriating what he had said was, how hurtful it was that everybody seemed to have enjoyed what he said. But it gets so bloody tiring dealing with the reactions. Not just the accusations of “political correctness,” the rolled eyes or the “Aren’t you being too sensitive?” charges, inevitably delivered with a smile. But also the downward glances, the stammering, or even the apologies that so often greet an objection: “Oh, I’m sorry. I know that you … uh… Native Americans object to that.”

As if it’s okay to deploy a slur when no member of the slurred ethnicity is around to be insulted? As if racism only matters to people of color? As if every one of us is not harmed to the core by such talk about any ethnicity and should object to it?

This incident – I can recount a dozen others I’ve witnessed in the 21st Century – made me ponder a great deal the theme I’ve heard so much of recently, on-line and off, that race and racism have been transcended in America. That we no longer need to talk about these matters because, well, because talking about them only engenders bad feelings about something that is fixed except in a few backward locales by people who will be dead soon anyway. That, 45 years after the summer day Reverend King made that soaring speech on the Washington Mall, his dream is wholly achieved.

Nobody can deny that tremendous progress has been made. Progress that is a testament both to the message of universal legal equality in the nation’s founding document and two centuries of fierce and costly struggle by people of color and their white allies to transform that message into reality. A testament to people’s willingness to change themselves, to surrender their prejudices and fears, to recognize injustice and do something about it, even to give up their lives if that’s what it takes. That progress cannot be sneered at. It reflects an America and Americans of all colors at their best.

Racism nonetheless remains a chronic influence in our lives. Yet many white people say they don’t want to talk about race. They say they’re sick of talking about it. That stuff is all in the past, they say, and wonder aloud why we can’t talk about something else. I think what most are really saying is that they don’t want to listen to talk about race.

Because, in fact, Americans talk about race all the time. It suffuses discussions of economics, community affairs, the military, policing, education, drugs. These days, except for the movies, some lyrics and the occasional “macaca,” we hear fewer and fewer of those slurs that when I was a kid we were daily bathed in. Racist talk now is mostly coded talk – the “underclass,” the “inner city,” “culture of poverty.” But that is dishonest talk, a masquerade of spin, not candid, uncomfortable conversations about racism that confront its deeper meanings and reduces its power. Not honest discussions that reach beyond personal racial prejudice and stereotypes – which can afflict people of any color – but rather into the deeply entrenched societal racism that persists even though racist laws have long been struck from the books. Not superficial pollyanna kumbaya conversations about diversity, multiculturalism and pluralism, but straightforward, heart-to-heart, often painful, sometimes angry discussions.

Being tired of talking about race and racism is not the sole province of white people. Many people of color feel the same way. Tired, among other things, of having to explain, once again, that white privilege didn’t disappear with the Civil Rights Act or affirmative action. Tired of talking about racism because it so often arouses not just the pain but also the anger, which, however, justified, injects fear into the conversation. Necessary as the anger may be to raising the consciousness of those whom racism oppresses, the only thing that kills conversation faster than anger is the fear which the anger engenders.

Being tired of talking about race and racism is not the sole province of white people. Many people of color feel the same way. Tired, among other things, of having to explain, once again, that white privilege didn’t disappear with the Civil Rights Act or affirmative action. Tired of talking about racism because it so often arouses not just the pain but also the anger, which, however, justified, injects fear into the conversation. Necessary as the anger may be to raising the consciousness of those whom racism oppresses, the only thing that kills conversation faster than anger is the fear which the anger engenders.

That is a conundrum that I dearly wish we could untangle. Because demystifying racism is impossible without continuing the conversation. Doing that means getting past being tired of talking about racism, beyond anger and fear. Defeating injustice means, as it always has in the past, not being afraid to talk about injustice, but being afraid not to talk about it. Frederick Douglass wasn’t afraid. W.E.B. Du Bois wasn’t. Septima Poinsette Clark wasn’t. César Chavez wasn’t. Fannie Lou Hamer wasn’t. Malcolm X wasn’t. Ralph McGill wasn’t. Martin Luther King wasn’t. Lyndon Baines Johnson wasn’t.

Let me offer one small bit to talking about racism on this day chosen – in the face of ferocious opposition – to officially commemorate the birthday of Dr. King. It’s a day when the invigorating “I have a dream” speech is reprised, his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” reprinted. These deserve the attention they receive. But far less often do we hear some other words of King’s, for instance, those he gave on February 25, 1967, at the Hilton Hotel in Los Angeles, and those he delivered on April 4, 1967, at the Riverside Baptist Church in Manhattan. These were costly speeches for him. When he said in Los Angeles that “I oppose the war in Vietnam because I love America,” he angered many who had hailed his leadership in the civil rights movement, including members of the NAACP who felt he was seeking to merge the antiwar movement with the civil rights movement. Others, including heavyweights in the media, criticized him for stepping outside the bounds of what they considered to be his acceptable role in American politics. In other words, he was “uppity.” Didn’t know “his place.” How dare this black man speak out against the war? There remain today many who believe people of color have no business engaging in certain conservations.

While this speech deals specifically with Vietnam, it contains the universal, timeless ideals with which King always framed his words. Here, in its entirety, is the courageous speech in which King first repudiated the war:

The Casualties of the War in Vietnam

I need not pause to say how happy I am to have the privilege of being a participant in this significant symposium. In these days of emotional tension when the problems of the world are gigantic in extent and chaotic in detail, there is no greater need than for sober-thinking, healthy debate, creative dissent and enlightened discussion. This is why this symposium is so important.

I would like to speak to you candidly and forthrightly this afternoon about our present involvement in Viet Nam. I have chosen as a subject, “The Casualties of the War In Viet Nam.” We are all aware of the nightmarish physical casualties. We see them in our living rooms in all of their tragic dimensions on television screens, and we read about them on our subway and bus rides in daily newspaper accounts. We see the rice fields of a small Asian country being trampled at will and burned at whim: we see grief-stricken mothers with crying babies clutched in their arms as they watch their little huts burst forth into flames; we see the fields and valleys of battle being painted with humankind’s blood; we see the broken bodies left prostrate in countless fields; we see young men being sent home half-men–physically handicapped and mentally deranged. Most tragic of all is the casualty list among children. Some one million Vietnamese children have been casualties of this brutal war. A war in which children are incinerated by napalm, in which American soldiers die in mounting numbers while other American soldiers, according to press accounts, in unrestrained hatred shoot the wounded enemy as they lie on the ground, is a war that mutilates the conscience. These casualties are enough to cause all men to rise up with righteous indignation and oppose the very nature of this war.

But the physical casualties of the war in Viet Nam are not alone the catastrophies. The casualties of principles and values are equally disastrous and injurious. Indeed, they are ultimately more harmful because they are self-perpetuating. If the casualties of principle are not healed, the physical casualties will continue to mount.

One of the first casualties of the war in Viet Nam was the Charter of the United Nations. In taking armed action against the Vietcong and North Viet Nam, the United States clearly violated the United Nations charter which provides, in Chapter I, Article II (4)

All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.

and in Chapter VII, (39)

The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression, and shall make recommendations or shall decide what measures shall be taken… to maintain or restore international peace and security.

It is very obvious that our government blatantly violated its obligation under the charter of the United Nations to submit to the Security Council its charge of aggression against North Viet Nam. Instead we unilaterally launched an all-out war on Asian soil. In the process we have underminded the purpose of the United Nations and caused its effectiveness to atrophy. We have also placed our nation in the position of being morally and politically isolated. Even the long standing allies of our nation have adamantly refused to join our government in this ugly war. As Americans and lovers of Democracy we should carefully ponder the consequences of our nation’s declining moral status in the world.

The second casualty of the war in Viet Nam is the principle of self-determination. By entering a war that is little more than a domestic civil war, America has ended up supporting a new form of colonialism covered up by certain niceties of complexity. Whether we realize it or not our participation in the war in Viet Nam is an ominous expression of our lack of sympathy for the oppressed, our paranoid anti-Communism, our failure to feel the ache and anguish of the have nots. It reveals our willingness to continue particpating in neo-colonialist adventures.

A brief look at the background and history of this war reveals with brutal clarity and ugliness of our policy. The Vietnamese people proclaimed their own independence in 1945 after a combined French and Japanese occupation, and before the Communist revolution in China. They were led by the now well-known Ho Chi Minh. Even though they quoted the American Declaration of Independence in their own document of freedom, we refused to recognize them. Instead, we decided to support France in its re-conquest of her former colony.

President Truman felt then that the Vietnamese people were not “ready” for independence, and we again fell victim to the deadly western arrogance that has poisoned the international atmosphere for so long. With that tragic decision we rejected a revolutionary government seeking self-determination, and a government that had been established not by China (for whom the Vietnamese have no great love) but by clearly indigenous forces that included some Communists.

For nine years following 1945 we denied the people of Viet Nam the right to independence. For nine years we vigorously supported the French in their abortive effort to re-colonize Viet Nam.

Before the end of the war we were meeting 80% of the French war costs. Even before the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu, they began to despair of their reckless action, but we did not. We encouraged them with our huge financial and military supplies to continue the war even after they had lost the will.

During this period United States governmental officials began to brainwash the American public. John Foster Dulles assiduously sought to prove that Indo-China was essential to our security against the Chinese Communist peril. When a negotiated settlement of the war was reached in 1954, through the Geneva Accord, it was done against our will. After doing all that we could to sabotage the planning for the Geneva Accord, we finally refused to sign it.

Soon after this we helped install Ngo Dihn Diem. We supported him in his betrayal of the Geneva Accord and his refusal to have the promised 1956 election. We watched with approval as he engaged in ruthless and bloddy persecution of all opposition forces. When Diem’s infamous actions finally led to the formation of The National Liberation Front, the American public was duped into believing that the civil rebellion was being waged by puppets from Hanoi. As Douglas Pike wrote: “In horror, Americans helplessly watched Diem tear apart the fabric of Vietnamese society more effectively than the Communists had ever been able to do it. It was the most efficient act of his entire career.”

Since Diem’s death we have actively supported another dozen military dictatorships all in the name of fighting for freedom. When it became evident that these regimes could not defeat the Vietcong, we began to steadily increase our forces, calling them “military advisers” rather than fighting soldiers.

Today we are fighting an all-out war–undeclared by Congress. We have well over 300,000 American servicemen fighting in that benighted and unhappy country. American planes are bombing the territory of another country, and we are committing atrocities equal to any perpetrated by the Vietcong. This is the third largest war in American history.

All of this reveals that we are in an untenable position morally and politically. We are left standing before the world glutted by our barbarity. We are engaged in a war that seeks to turn the clock of history back and perpetuate white colonialism. The greatest irony and tragedy of all is that our nation which initiated so much of the revolutionary spirit of the modern world, is not cast in the mold of being an arch anti-revolutionary.

A third casualty of the war in Viet Nam is the Great Society. This confused war has played havoc with our domestic destinies.

Despite feeble protestations to the contrary, the promises of the Great Society have been shot down on the battlefield of Viet Nam. The pursuit of this widened war has narrowed domestic welfare programs, making the poor, white and Negro, bear the heaviest burdens both at the front and at home.

While the anti-poverty program is cautiously initiated, zealously supervised and evaluated for immediate results, billions are liberally expended for this ill-considered war. The recently revealed mis-estimate of the war budget amounts to ten billions of dollars for a single year. This error alone is more than five times the amount committed to anti-poverty programs. The security we profess to seek in foreign adventures we will lose in our decaying cities. The bombs in Viet Nam explode at home: they destroy the hope s and possibilities for a decent America.

If we reversed investments and gave the armed forces the antipoverty budget, the generals could be forgiven if they walked off the battlefield in disgust.

Poverty, urban problems and social progress generally are ignored when the guns of war become a national obsession. When it is not our security that is at stake, but questionable and vague commitments to reactionary regimes, values disintegrate into foolish and adolescent slogans.

It is estimated that we spend $322,000 for each enemy we kill, while we spend in the so-called war on poverty in America only about $53.00 for each person classified as “poor. And much of that 53 dollars goes for salaries of people who are not poor. We have escalated the war in Viet Nam and de-escalated the skirmish against poverty. It challenges the imagination to contemplate what lives we could transform if we were to cease killing.

At this moment in history it is irrefutable that our world prestige is pathetically frail. Our war policy excites pronounced contempt and aversion virtually everywhere. Even when some national government s, for reasons of economic and diplomatic interest do not condemn us, their people in surprising measure have made clear they do not share the official policy.

We are isolated in our false values in a world demanding social and economic justice. We must undergo a vigorous re-ordering of our national priorities.

A fourth casualty of the war in Viet Nam is the humility of our nation. Through rugged determination, scientific and technological progress and dazzling achievements, America has become the richest and most powerful nation in the world. We have built machines that think and instruments that peer into the unfathomable ranges of interstellar space. We have built gargantuan bridges to span the seas and gigantic buildings to kiss the skies. Through our airplanes and spaceships we have dwarfed distance and placed time in chains, and through our submarines we have penetrated oceanic depths. This year our national gross product will reach the astounding figure of 780 billion dollars. All of this is a staggering picture of our great power.

But honesty impells me to admit that our power has often made us arrogant. We feel that our money can do anything. We arrogantly feel that we have everything to teach other nations and nothing to learn from them. We often arrogantly feel that we have some divine, messianic mission to police the whole world. We are arrogant in not allowing young nations to go through the same growing pains, turbulence and revolution that characterized cur history. We are arrogant in our contention that we have some sacred mission to protect people from totalitarian rule, while we make little use of our power to end the evils of South Africa and Rhodesia, and while we are in fact supporting dictatorships with guns and money under the guise of fighting Communism. We are arrogant in professing to be concerned about the freedom of foreign nations while not setting our own house in order. Many of our Senators and Congressmen vote joyously to appropriate billions of dollars for war in Viet Nam, and these same Senators and Congressmen vote loudly against a Fair Housing Bill to make it possible for a Negro veteran of Viet Nam to purchase a decent home. We arm Negro soldiers to kill on foreign battlefields, but offer little protection for their relatives from beatings and killings in our own south. We are willing to make the Negro 100% of a citizen in warfare, but reduce him to 50% of a citizen on American soil. Of all the good things in life the Negro has approximately one half those of whites; of the bad he has twice that of whites.

Thus, half of all Negroes live in substandard housing and Negroes have half the income of whites. When we turn to the negative experiences of life, the Negro has a double share. There are twice as many unemployed. The infant mortality rate is double that of white. There are twice as many Negroes in combat in Viet Nam at the beginning of 1967 and twice as many died in action (20.6%) in proportion to their numbers in the population as whites.

All of this reveals that our nation has not yet used its vast resources of power to end the long night of poverty, racism and man’s inhumanity to man. Enlarged power means enlarged peril if there is not concommitant growth of the soul. Genuine power is the right use of strength. If our nation’s strength is not used responsibly and with restraint, it will be, following Acton’s dictum, power that tends to corrupt and absolute power that corrupts absolutely. Our arrogance can be our doom. It can bring the curtains down on our national drama. Ultimately a great nation is a compassionate nation. We are challenged in these turbulent days to use our power to speed up the day when “every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain.”

A fifth casualty of the war in Viet Nam is the principle of dissent. An ugly repressive sentiment to silence peace-seekers depicts advocates of immediate negotiation under terms of the Geneva agreement and persons who call for a cessation of bombings in the north as quasi-traitors, fools or venal enemies of our soldiers and institutions. Free speech and the privilege of dissent and discussion are rights being shot down by Bombers in Viet Nam. When those who stand for peace are so vilified it is time to consider where we are going and whether free speech has not become one of the major casualties of the war.

Curtailment of free speech is rationalized on grounds that a more compelling American tradition forbids critism of the government when the nation is at war. More than a century ago when we were in a declared state of war with Mexico, a first term congressman by the name of Abraham Lincoln stood in the halls of Congress and fearlessly denounced that war.

Congressman Abraham Lincoln of Illinois had not heard of this tradition or he was not inclined to respect it. Nor had Thoreau and Emerson and many other philosophers who shaped our democratic principles. Nothing can be more destructive of our fundamental democratic traditions than the vicious effort to silence dissenters.

A sixth casualty of the war in Viet Nam is the prospects of mankind’s survival. This war has created the climate for greater armament and further expansion of destructive nuclear power.

One of the most persistent ambiguities that we face is that everybody talks about peace as a goal. However, it does not take sharpest-eyed sophistication to discern that while everybody talks about peace, peace has become practically nobody’s business among the power-wielders. Many men cry peace! peace! but they refuse to do the things that make for peace.

The large power blocs of the world talk passionately of pursuing peace while burgeoning defense budgets that already bulge, enlarging already awesome armies, and devising even more devastating weapons. Call the roll of those who sing the glad tidings of peace and one’s ears will be surprised by the responding sounds. The heads of all of the nations issue clarion calls for peace yet these destiny determiners come accompanied by a band and a brigand of national choristers, each bearing unsheathed swords rather than olive branches.

The stages of history are replete with the chants and choruses of the conquerors of old who came killing in pursuit of peace. Alexander, Ghenghis Khan, Julius Caesar, Charlemagne, and Napoleon were akin in their seeking a peaceful world order, a world fashioned after their selfish conceptions of an ideal existence. Each sought a world at peace which would personify their egotistic dreams. Even within the life-span of most of us, another megalomaniac strode across the world stage. He sent his blitzkrieg-bent legions blazing across Europe, bringing havoc and holocaust in his wake. There is grave irony in the fact that Hitler could come forth, following the nakedly aggressive expansionist theories he revealed in Mein Kampf, and do it all in the name of peace.

So when I see in this day the leaders of nations similarly talking peace while preparing for war, I take frightful pause. When I see our country today intervening in what is basically a civil war, destroying hundred of thousands of Vietnamese children with napalm, leaving broken bodies in countless fields and sending home half-men, mutilated, mentally and physically; when I see the recalcitrant unwillingness of our government to create the atmosphere for a negotiated settlement of this awful conflict by halting bombings in the North and agreeing to talk with the Vietcong–and all this in the name of pursuing the goal of peace–I tremble for our world. I do so not only from dire recall of the nightmares wreaked in the wars of yesterday, but also from dreadful realization of today’s possible nuclear destructiveness, and tomorrow’s even more damnable prospects.

In the light of all this, I say that we must narrow the gaping chasm between our proclamations of peace and our lowly deeds which precipitate and perpetuate war. We are called upon to look up from the quagmire of military programs and defense commitments and read history’s signposts and today’s trends.

The past is prophetic in that it asserts loudly that wars are poor chisels for carving out peaceful tomorrows. One day we must come to see that peace is not merely a distant goal that we seek, but a means by which we arrive at that goal. We must pursue peaceful ends through peaceful means. How much longer must we play at deadly war games before we heed the plaintive pleas of the unnumbered dead and maimed of past wars? Why can’t we at long last grow up, and take off our blindfolds, chart new courses, put our hands to the rudder and set sail for the distant destination, the port city of peace?

President John F. Kennedy said on one occasion, “Mankind must put an end to war or war will put an end to mankind.” Wisdom born of experience should tell us that war is obsolete. There may have been a time when war served as a negative good by preventing the spread and growth of an evil force, but the destructive power of modern weapons eliminates even the possibility that war may serve as a negative good. If we assume that life is worth living and that man has a right to survive, then we must find an alternative to war. In a day when vehicles hurtle through outer space and guided ballistic missiles carve highways of death through the stratosphere, no nation can claim victory in war. A so-called limited war will leave little more than a calamitous legacy of human suffering, political turmoil, and spiritual disillusionment. A world war–God forbid!–will leave only smouldering ashes as a mute testimony of a human race whose folly led inexorably to ultimate death. So if modern man continues to flirt unhesitatingly with war, he will transform his earthly habitat into an inferno such as even the mind of Dante could not imagine.

I do not wish to minimize the complexity of the problems that need to be faced in achieving disarmament and peace. But I think it is a fact that we shall not have the will, the courage and the in sight to deal with such matters unless in this field we are prepared to undergo a mental and spiritual re-evaluation, a change of focus which will enable us to see that the things which seem most real and powerful are indeed now unreal and have come under the sentence of death. We need to make a supreme effort to generate the readiness, indeed the eagerness, to enter into the new world which is now possible.

We will not build a peaceful world by following a negative path. It is not enough to say “we must not wage war.” It is necessary to love peace and sacrifice for it. We must concentrate not merely on the negative expulsion of war, but on the positive affirmation of peace. There is a fascinating little story that is preserved for us in Greek literature about Ulysses and the Sirens. The Sirens had the ability to sing so sweetly that sailors could not resist steering toward their island. Many ships were lured upon the rocks and the men forgot home, duty and honor as they flung themselves into the sea to be embraced by arms that drew them down to death. Ulysses, determined not to be lured by the Sirens, first decided to tie himself tightly to the mast of his boat and his crew stuffed their ears with wax. But finally he and his crew learned a better way to save themselves: they took on board the beautiful singer Orpheus whose melodies were sweeter than the music of the Sirens. When Orpheus sang, who bothered to listen to the Sirens? So we must fix our visions not merely on the negative expulsion of war. But upon the positive affirmation of peace. We must see that peace represents a sweeter music, a cosmic melody that is far superior to the discords of war. Somehow we must transform the dynamics of the world power struggle from the negative nuclear arms race which no one can win to a positive contest to harness man’s creative genius for the purpose of making peace and prosperity a reality for all of the nations of the world. In short, we must shift the arms race into a “peace race.” If we have the will and determination to mount such a peace offensive we will unlock hitherto tightly sealed doors of hope and bring new light into the dark chambers of pessimism.

Let me say finally that I oppose the war in Viet Nam because I love America. I speak out against it not in anger but with anxiety and sorrow in my heart, and above all with a passionate desire to see our beloved country stand as the moral example of the world. I speak out against this war because I am disappointed with America. There can be no great disappointment where there is no great love. I am disappointed with our failure to deal positively and forthrightly with the triple evils of racism, Extreme materialism and militarism. We are presently moving down a dead-end road that can lead to national disaster.

Jesus once told a parable of a young man who left home and wandered into a far country where, in adventure after adventure and sensation after sensation, he sought life. But he never found it; he found only frustration and bewilderment. The farther he moved from his father’s house, the closer he came to the house of despair. The more he did what he liked, the less he liked what he did. After the boy had wasted all, a famine developed in the land, and he ended up seeking food in a pig’s trough. But the story does not end there. It goes on to say that in this state of disillusionment, blinding frustration and homesickness, the boy “came to himself” and said, “I will arise and go to my father, and will say to him, Father, I have sinned against heaven and before thee.” The prodigal son was not himself when he left his father’s house or when he dreamed that pleasure was the end of life. Only when he made up his mind to go home and be a son again did he really come to himself. The parable ends with the boy returning home to find a loving father waiting with outstretched arms and heart filled with unutterable job.

This is an analogy of what America confronts today. Like all human analogies, it is imperfect, but it does suggest some parallels worth considering. America has strayed to the far country of racism and militarism. The home that all too many Americans left was solidly structured idealistically. Its pillars were soundly grounded in the insights of our Judeo-Christian heritage–all men are made in the image of God; all men are brothers; all men are created equal; every man is heir to a legacy of dignity and worth; every man has rights that are neither conferred by nor derived from the state, they are God-given; out of one blood God made all men to dwell upon the face of the earth. What a marvelous foundation for any home! What a glorious and healthy place to inhabit! But America strayed away; and this unnatural excursion has brought only confusion and bewilderment. It has left hearts aching with guilt and minds distorted with irrationality. It has driven wisdom from her sacred throne. This long and callous sojourn in the far country of racism and militarism has brought a moral and spiritual famine to the nation.

It is time for all people of conscience to call upon America to return to her true home of brotherhood and peaceful pursuits. We cannot remain silent as our nation engages in one of history’s most cruel and senseless wars. America must continue to have, during these days of human travail, a company of creative dissenters. We need them because the thunder of their fearless voices will be the only sound stronger than the blasts of bombs and the clamor of war hysteria.

Those of us who love peace must organize as effectively as the war hawks. As they spread the propaganda of war we must spread the propaganda of peace. We must combine the fervor of the civil rights movement with the peace movement. We must demonstrate, teach and preach, until the very foundations of our nation are shaken. We must work unceasingly to lift this nation that we love to a higher destiny, to a new platens of compassion, to a more noble expression of humane-ness.

I have tried to be honest today. To be honest is to confront the truth. To be honest is to realize that the ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of convenience and moments of comfort, but where he stands in moments of challenge and moments of controversy. However unpleasant and inconvenient the truth may be, I believe we must expose and face it if we are to achieve a better quality of American life.

Just the other day, the distinguished American historian, Henry Steele Commager, told a Senate Committee: “Justice Holmes used to say that the first lesson a judge had to learn was that he was not God… we do tend perhaps more than other nations, to transform our wars into crusades… our current involvement in Viet Nam is cast, increasingly, into a moral mold… It is my feeling that we do not have the resources, material, intellectual or moral, to be at once an American power, a European power and an Asian power.”

I agree with Mr. Commager. And I would suggest that there is, however, another kind of power that America can and should be. It is a moral power, a power harnessed to the service of peace and human beings, not an inhumane power unleashed against defenseless people. All the world knows that America is a great military power. We need not be diligent in seeking to prove it. We must now show the world our moral power.

There is an element of urgency in our re-directing American powers. We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history there is such a thing as being too late. Procrastination is still the chief of time.

Life often leaves us standing bare, naked and dejected with a lost opportunity. The “tide in the affairs of men” does not remain at flood: it ebbs. We may cry out desperately for time to pause in her passage, but time is adamant to every plea and rushes on. Over the bleached bones and jumbled residue of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words: “Too late. ” There is an invisible book of life that faithfully records our vigilance or our neglect. “The moving finger writes, and having writ moves on…” We still have a choice today: nonviolent co-existence or violent co-annihilation. History will record the choice we made. It is still not too late to make the proper choice. If we decide to become a moral power we will be able to transform the jangling discords of this world into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. If we make the wise decision we will be able to transform our pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of peace. This will be a glorious day. In reaching it we can fulfill the noblest of American dreams.

Happy birthday, Dr. King. We miss your voice. May we be fortunate enough never to lose your clarity of vision or courage never to stay silent.

I was standing in a massive crowd in Washington DC to get into the grand opening of the National Museum of the Native American a few years ago. For once the majority of the crowd was Native American. It was wonderful. Behind me two caucasian women were chatting about sports and one commented about the recent local game and said “Redskins” loudly.

My body stiffened. I turned around and glared at her. She didn’t see me. I could not believe that someone standing in a crowd of Native Americans could be so oblivious. I wanted to say something but decided it would just embarrass her since I think she meant no harm. It’s just an amazingly offensive word to me and I CANNOT BELIEVE THE NFL STILL USES IT TODAY. It makes it “ok” to say.

It is not ok.