( – promoted by navajo)

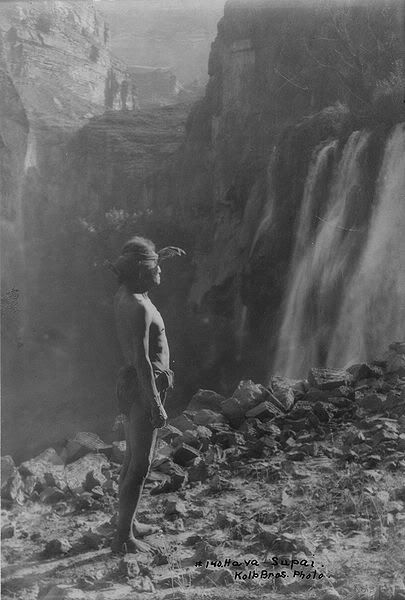

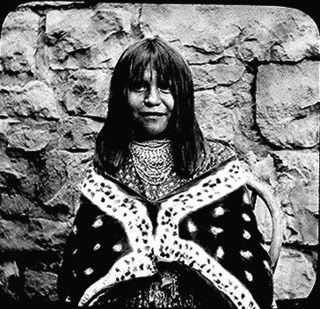

American Indians have lived in and have utilized the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River for thousands of years. The Havasupai, whose farms are in the bottom of the canyon, were visited by the Spanish under the leadership of the missionary Francisco Garces in 1776. The Spanish followed a narrow trail into Cataract Canyon, a tributary to the Grand Canyon. The trail was narrow, steep, and perilous with a thousand foot drop-off. Some of Garces’ men finished the journey on their hands and knees as they were afraid to stand up. At the bottom of the canyon they encountered the Havasupai who were cultivating about 400 acres of land.

The United States acquired the Grand Canyon following a brief war with Mexico in 1848. In 1893, much of the winter range used by the Havasupai was set aside as the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve by executive order of President Benjamin Harrison. There was little or no consideration or recognition of Havasupai rights within this area.

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Grand Canyon. He rode down into the canyon and found Havasupai families headed by Yavñmi’ Gswedva (Dangling Beard) and Burro living at Indian Garden. According Havasupai oral tradition, President Roosevelt spoke to Gswedva (called Big Jim by the Americans) and informed him, through an interpreter, of the federal government’s intent to locate a park for the American people on Gswedva’s and Burro’s garden lands below the rim. To make such a park possible, he urged them to vacate the area.

In 1914, concerned about the talk regarding the establishment of Grand Canyon National Park, the Indian agent for the Havasupai made a request (one of several) to obtain plateau land for them. He wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

“Out of this abundance it seems that these peacable [sic] and quiet people who have never opposed the approach of the white man nor disputed his progress might have enough on which to make an honest and plentiful living”

With regard to the requested plateau land, he wrote:

“This land is within the Forest Reserve, but in so far as the timber is concerned is of no value whatever.”

Legislation was introduced in Congress in 1917 to create the Grand Canyon National Park. The legislation made no mention of the Havasupai who inhabited the area and it is quite probable that the Secretary of the Interior was unaware that this Indian tribe was living in Cataract Canyon.

Grand Canyon National Park:

Congress created the Grand Canyon National Park in 1919. With regard to the Havasupai, the aboriginal dwellers of the area, the legislation states:

“That nothing herein contained shall affect the rights of the Havasupai Tribe of Indians to the use and occupancy of the bottom lands of the Canyon of Cataract Creek.”

Tribal members, at the discretion of the Secretary of the Interior, may be allowed to use and occupy other tracts of land within the park for agricultural purposes.

The newly created National Park is bordered by three Indian reservations: Navajo, Havasupai, and Hualapai. In addition, five more tribes consider parts of the Grand Canyon to be sacred areas: Hopi, Zuni, Kaibab Paiute, Shivwits Paiute, and San Juan Paiute.

In 1926, the National Park Service began construction of a sewer line to the Grand Canyon Village. The new sewer line was intended to service the growing non-Indian community at the South Rim. In constructing the sewer line, several Havasupai camps were relocated. The park superintendent set off a 160-acre plot for the Havasupai and told them that they could stay on it.

In 1926, the National Park Service proposed adjusting the Grand Canyon National Park boundary to include the Havasupai access road. While the Park Service usually goes to great lengths to avoid the private property of non-Indians, there was no concern for the Havasupai.

In 1928, much to the annoyance of the National Park Service, the Havasupai family of Burro was still farming Indian Garden within the Grand Canyon National Park. Two park rangers went down and chased him out. It was reported that Burro stood on the rim, looked down at the place and wept for it.

In 1934, the National Park Service decided that the traditional Havasupai homes west of Grand Canyon Village were an eyesore. Consequently the Park Service built ten cabins for the Havasupai. The Park Service then tore down and burned the traditional homes. The new cabins were rented to the Havasupai for $5 per month, which included neither maintenance nor repair. By moving the Havasupai families into rented cabins, the Park Service changed Havasupai into tenants and thus erased their aboriginal status.

The National Park Service in 1936 issued an order which stated that only Indians who worked in the park may be allowed to live in Yosemite (California), Grand Canyon (Arizona), and Death Valley (California).

In 1939, a non-Indian leased land from the state and built a fence around a spring in Cataract Canyon. This blocked the Havasupai cattle from the watering hole and 28 head of cattle died. The Havasupai complained to the National Park Service. The National Park Service contacted the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and suggested that the Havasupai be placed on the Hualapai reservation and that the 518 acres of the Havasupai reservation be transferred to the Grand Canyon National Park.

In 1940, the National Park Service, concerned about the Havasupai and Grand Canyon National Park, asked the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

“What likelihood is there of moving the Supai Indians to the Hualapai Reservation and adding the Havasupai Reservation to the national park?”

This action showed shocking disregard to the Havasupais’ seven-hundred-year connection to their homeland.

In 1940, the superintendent of Grand Canyon National Park was reprimanded by a superior:

“Please make a point of referring to Indians, living or archaeological, as men, women, and children-not as bucks or braves, squaws or papooses.”

In 1955, the National Park Service informed the Havasupai families in the Grand Canyon National Park that they could remain only if they were employed. At this time, Grand Canyon National Park and the various concessioners began terminating Havasupai jobs within the park. Park officials began dismantling homes at the Havasupai residence camp. The Bureau of Indian Affairs had a truck available to haul the dispossessed and their belongings away.

In 1968, the Indian Claims Commission offered the Havasupai more than $1.2 million for the government’s deprivation of more than 2 million acres of their former range. The settlement came out to 55 cents per acre. The lands involved included a portion of the Grand Canyon National Park.

The Havasupai held a public meeting on the offer. Tribal chairman Daniel Kaska urged those present not to accept the offer:

“We want the land; we don’t want the money. What happens to our land if we take this money?”

The tribal attorney, however, informed them that this course of action was not available to them: if they refused the money, then they would get nothing. When put to a vote, 52 voted to accept the offer and only 10 voted against it.

The following year, having learned of the Indian Court of Claims judgment regarding the Havasupai land claim, the National Park Service began consulting with the Sierra Club and other groups to incorporate the tribe’s permit areas into the Grand Canyon National Park. This would place more restrictions on tribal use. The tribe was not consulted.

In 1971, the National Park Service and the Sierra Club completed the third draft of their plan for incorporating Havasupai permit areas into the Grand Canyon National Park. However, the tribe’s attorney obtained a copy of the planning document and notified the tribe. In the master plan map, there was no Havasupai Reservation: the area was shown as a part of the park.

In response to their discovery of this planning process, the Havasupai met with the superintendent of Grand Canyon National Park. At the public hearing regarding the plan, tribal chairman Lee Marshall stated:

“I heard you people talking about the Grand Canyon. Well, you’re looking at it. I am the Grand Canyon.”

He then went on to ask for the return of the Park Service campground and the Havasupai residence area at Grand Canyon Village. He asked that the park provide the Havasupai preferential employment. Following the public meeting, the Havasupai Tribal Council held an all-day meeting with the elders. The tribal elders indicated that they wanted the return of park and forest permit areas. Neither the Park Service nor the Forest Service, however, would consider the tribe’s plan.

In 1972, the Havasupai appealed to both the Secretary of the Interior (who is in charge of national parks, including the Grand Canyon National Park) and the Secretary of Agriculture (who is in charge of national forests). Concerning their traditional use areas which are administered by the Forest Service and the National Park Service, they wrote:

“We care more deeply for the beauty of our land than Sunday hikers or professional environmentalists because this land is part of us, and we live on it… We are human beings with the right to survive, not rocks or dust. This is not a zoo.”

While both agencies promised to respond to the letter, neither did. The Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth mounted a nationwide campaign of opposition to the Havasupai land return. Their campaign left the impression that the Havasupai planned to put Disneyland on the plateau of the Grand Canyon.

Finally, in 1975, President Gerald Ford signed legislation which enlarged the Havasupai reservation and guaranteed them the use of 95,000 acres within Grand Canyon National Park. The government also acknowledged the rights of the Havasupai to access sacred sites which are outside of their reservation. With this act, they had overcome numerous political obstacles and what seemed impossible odds.

Leave a Reply