( – promoted by navajo)

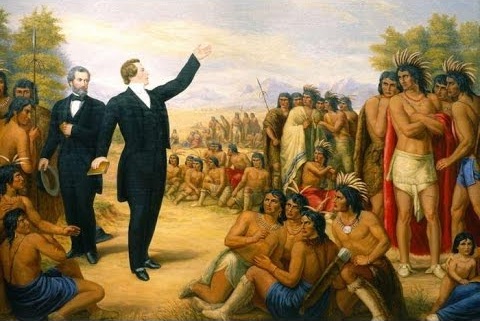

For thousands of years the Hopi Indians have lived in permanent farming villages, called Pueblos by the Spanish. In 1847, the Mormons entered what is now Utah and began to proselytize the Utes, Paiutes, and Shoshones who have traditionally lived in this area. Within a decade, the Mormon missionaries began to move south into present-day Arizona and to seek converts among the Hopi. Overall the Mormon missionary work attracted only a few converts, but it was more successful than other Christian faiths. This diary looks at the nineteenth century Mormon missionary activities among the Hopi.

Jacob Hamblin reported in 1858 that the Mormon mission to the Paiute in southern Utah had not been successful and suggested that missionary efforts be redirected to the Hopi and the Navajo. Consequently, Jacob Hamblin and eleven other men set out from Utah to make contact with the Hopi villages south of the Colorado River (in Arizona). The group was charged by Mormon leader Brigham Young to make contact with the Hopi and to preach the gospel to them. The party reached the village of Oraibi and the Hopi treated them with friendship.

Two years later, Jacob Hamblin attempted to return to the Hopi, but was stopped by a group of unfriendly Navajo. Over the next few years, raids by the Navajo and by the Paiute against Mormon settlements (sometimes called the “Mormon-Indian wars”) would result in at least 70 deaths and would enrich the Navajo with 1,200 horses and cattle.

In 1862, Mormon missionary Jacob Hamblin arrived at the Hopi village of Oraibi and helped establish a Hopi settlement at Moencopi. In addition to bringing Mormonism to the Hopi, he also brought some new crops including turban squash, safflower, and sorghum.

In 1863, the Mormon missionaries to the Hopi village of Oraibi were greeted as men of destiny. According to Hopi oral tradition, there would be a time when bearded prophets, usually said to be three in number, would lead the Hopi back across the Colorado River when they had come as the result of an ancient treaty with the Paiutes. The Hopi had predicted that the Mormons would come and live among them. The Mormons also heard about the sacred stone which is kept in an Oraibi kiva. This stone, according to Hopi tradition, carried inscriptions which described the advent of prophets from the west. The stone and indeed the entire ritual and tradition of the Hopis, seemed to suggest parallels to Mormon doctrines and ceremonies.

At the same time, a Hopi delegation was taken to Salt Lake City where they met with experts on the Welsh language. There was a belief at this time that the Hopi had some sort of mysterious connection with the Welsh. According to a story concocted in England in 1580, Prince Madoc of Wales had led an expedition to Florida in 1170, thereby establishing England’s claim to North America under the Discovery Doctrine. During the 19th and 20th centuries, many people believed that Indian tribes, such as the Mandan, Hopi, and Kootenai, were the Welch-speaking descendents of Prince Madoc. The story was a hoax and the Welsh language experts soon determined that Hopi, a Uto-Aztecan language, was unrelated to any European language.

In 1870, John Wesley Powell, the first American to explore the Colorado River, was taken to the Hopi village of Oraibi by Mormon missionary Jacob Hamblin. He stayed in the village for several weeks. Powell had great respect for Hopi religious traditions, and after a while he gained the trust of many Hopis. Upon his return to Washington, D.C., Powell fought successfully against plans by the Indian Office which would have harmed the Hopi. He considered himself to be a friend of the Hopi.

Tuuvi, a Hopi leader from the village of Oraibi converted to Mormonism in 1870 and settled near the village of Moencopi. In 1875, the Mormons established their own village near the Hopi pueblo of Moencopi. They named their new village Tuba City in honor of Tuuvi (whom they called Chief Tuba).

At this time the United States government was actively discouraging and suppressing all forms of Native American religion. The government was also active in discouraging and suppressing Mormonism. Not only had Mormon missionaries converted a few Hopis, but they had also expanded their activities into Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico and performed more than 100 baptisms. This action alarmed the Presbyterians who had control over several southwestern tribes, including the Zuni. The Presbyterians felt that the Mormons were a greater threat than paganism.

In 1876, the Indian Agent for the Hopi recommended to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs that a reservation be established for the Hopi to help block intrusions of Mormon settlers on their land. The Indian Office enthusiastically supported the plan, due in large part to the anti-Mormon attitude of both the Indian Office administration and the Army.

Six years later the Hopi Reservation was formally created by executive order of President Chester A. Arthur. The reservation was totally surrounded by the Navajo reservation and excluded the major Hopi village of Moenkopi (the area where the Mormons had been most active). The Hopi were not consulted in the creation of their reservation and its boundaries ignored a larger area that was settled and claimed by the Hopi.

While there may have been anti-Mormon sentiment that helped spur the establishment of the Hopi Reservation, a year later the Indian Agent asked for a detachment of Army Troops to help in gathering up Hopi children to be sent to the Mormon Intermountain School in Utah. The peace¬ful Hopis met the troops with a bombardment of rocks.

Leave a Reply