Utah’s Black Hawk War

During 1865 to 1867, American and Mormon settlers in Utah were engaged in a war with a small group of Ute, Paiute, and Navajo warriors under the leadership of Ute chief Black Hawk. As a result of the conflict, the American and Mormon settlers abandoned much of southern and central Utah. At least nine communities were abandoned. The main object of most of the Indian raids was to take cattle for food. The Black Hawk War caused an estimated $1.5 million in losses.

While the Black Hawk War involved only a small group of warriors, Black Hawk’s raiders were so effective that it was a common perception among the Mormon settlers that all of the Indians in the territory were at war.

Setting the Stage:

The Black Hawk war grew out of a complex set of circumstances which included the loss of Indian farms in Utah and the failure of the United States government to fulfill its treaty obligations. The Utes and the Paiutes had been displaced from their ancestral lands and they had been deprived of their economic base. As a result, they were left with only three options: they could starve, they could beg, or they could fight.

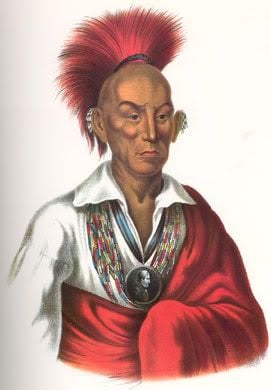

In 1863, Autenquer (Black Hawk), a San Pitch Ute war leader, began to form alliances with other Ute bands, as well as with Paiute and Navajo bands to raid Mormon communities. The Indians blamed the Mormons for stealing their country and fencing it in. One of the causes of the raids is hunger and the Indians raid the communities to get cattle to eat.

Two years later, the Treaty of Spanish Fork with the Paiute called for them to give up all lands claimed in Utah and to move to the Uintah Reservation. None of the signers of the treaty represented the Meadow Valley and Virgin River Paiute bands who were contesting Mormon encroachment on their territory.

Like the Paiute, the Ute also signed the Treaty of Spanish Fork in which they gave up all of their land in Utah except for the Uintah Valley. In exchange, the Ute were to receive $900,000 to be paid to them over 60 years and they were to be allowed to fish in all accustomed places and to gather roots and berries. All of the Ute chiefs, except for San Pitch, signed the treaty. San Pitch said: “If the talk is for us to trade the land in order to get the presents, I do not want any blankets or any clothing, if threat is the way they are to be got. I would rather do without them than to give up my title to the land I occupy. We want to live here as formerly.”

Kanosh opposed the treaty saying: “In past times, the Washington chiefs that came here from the United States would think and talk two ways and deceive us.”

Mormon leader Brigham Young, speaking for the United States, told the Ute: “If you do not sell your land to the Government, they will take it, whether you are willing to sell it or not.” Young also told them: “The land does not belong to you, nor to me, nor to the Government. It belongs to the Lord.”

Brigham Young assured them that they would receive houses, farms, cows, oxen, clothing, and other things. Because of his words, the chiefs signed the treaty.

The U.S. Senate refused to ratify the treaty because .of their disagreements with the Mormons. These disagreements with the Mormons had nothing to do with the Indians. The United States Senate wanted to punish the Mormons for their religious beliefs and refusing the treaty would increase the tensions between the Indians and the Mormon settlers.

The War:

In 1865, the conflicts between the Utes under the leadership of San Pitch subchief Black Hawk and the Mormon settlers intensified. The Indians, driven by hunger, stole some cattle and in the process some Mormons were killed. Mormon leader John Taylor stated: “Some want to kill the Indians promiscuously, because some of them have killed some of our people. This is not right. Let the guilty be punished and innocent go free.”

Black Hawk visited the Elk Mountain Ute to gain allies in his war against the Mormons. Black Hawk’s warriors were soon joined by Ute warriors from other bands as well as by Paiute and Navajo warriors. At most the Black Hawk’s forces numbered only 60 to 100 warriors during the conflict. About half of the warriors were Navajos or Paiutes.

In 1865, a Ute war party under the leadership of Black Hawk ambushed the Sanpete militia near Red Lake. While the warriors produced a heavy rate of fire, they overshot the militia and the bullets struck the lake behind them.

A Mormon militia force of 84 pursued a Ute war party up Salina Canyon. At a narrow point in the canyon, the militia unit was ambushed by Ute warriors who were hidden behind rocks, trees, and bushes. The militia managed to escape with only two men killed and two wounded.

A Mormon militia group fired blindly into a large cedar grove near Burrville, killing more than a dozen Indians, including women and children. The incident was not officially investigated.

Several Indian woman and children were held captive by a Mormon militia unit. One of the women struck one of the guards and in retaliation he shot the woman and the rest of the prisoners. The incident was not officially investigated.

In 1866, Ute chief San Pitch and several of his men were arrested near Nephi because of rumors that he had been involved in violence against the American settlers. San Pitch was told to bring in Black Hawk and his band or be shot. Since San Pitch did not have the power to influence Black Hawk and his warriors, he and his fellow prisoners broke jail rather than await execution. The escapees were hunted down and killed.

In another incident, 16 unarmed Paiutes, including women and children, were killed near Circleville. The Paiutes had been captured by the Mormons and were killed one at a time. Most had their throats slit. Three or four small children were spared and were adopted by Mormon families. While there were pleas for an investigation, federal and territorial officials took no action. This reluctance or inability of territorial and federal officials to follow proper legal procedures with the Indians helped to create a climate that allowed for continued misconduct.

At Panguitch Lake, the Paiute bands would not let the Mormons fish in the lake, but they would sell fish to them. In response, the Mormons declared the Paiutes to be involved with Black Hawk’s warriors and attacked a Paiute camp. They then declared a Paiute Mormon convert to be the chief and restored the peace. Following this, the lake became a fishing resort for non-Indians.

In 1866, Mormon leader Brigham Young wrote: “The Lamanites are hostile, let us exercise faith about them and learn what the will of the Lord is. Let us send our Interpreters to them and make presents and tell [them] they must stop fighting. It is better to give them $5000 than have to fight and kill them for they are of the House of Israel.”

In 1867, the body of Simeon, a Paiute, was found near Paragonah with a bullet wound in the back of his head. William H. Dame, president of the Prowan Stake of the Latter Day Saints church and colonel in the militia was instructed by Mormon leaders Brigham Young and George A. Smith that the murder of a peaceful Indian must be dealt with by civil authorities. Subsequently an investigation into the murder was undertaken. When some people questioned whether or not Simeon had actually been murdered, his body was exhumed and the bullet removed from his skull. As a result of the investigation, murder charges are brought against Thomas Jose. Jose was convicted of second degree murder and was sentenced to ten years in the territorial penitentiary. He served one year and was then pardoned by the territorial governor.

After the War:

In 1867, Black Hawk surrendered at the Uintah Reservation. He came without his men but gave information on those still at large. It was estimated that he had 58-64 warriors under him.

During the Black Hawk War, about 46 Mormon settlers were killed, including 11 women and children. Both sides killed noncombatants.

The primary purpose of most of the Indian raids was to obtain cattle. Black Hawk’s warriors captured about 5,000 cattle. This focus on cattle shows that the warriors were often desperate for food.

In 1869, the San Pitch Ute, once led by Autenquer (Black Hawk), followed the civil leader Tabby-to-kwana to the Uintah Valley Reservation. The Ute had been assured that they would be able to continue to hunt and gather on all public lands.

Following the war, Black Hawk toured many of the settlements in central and southern Utah, speaking to Mormon congregations and asking for their understanding and forgiveness. In speaking to these communities, Black Hawk emphasized that his people had been destitute and starving. Some of the Mormon settlers greeted him with understanding, while others, remembering the deaths of family and friends, rejected his offer of reconciliation.