Following the Civil War, the Indian nations located in Indian Territory (an area which would later become the state of Oklahoma) faced two massive forces. First, the federal government wanted to impose new treaties on them, treaties which were intended to punish them for their role in the Civil War. The federal government either forgot or ignored the fact that the Civil War had divided these nations and that many had supported the Union during the war.

The second, and perhaps more powerful force, was the concept of manifest destiny which was being carefully nurtured by the corporate news media and the school systems. It was America’s destiny to occupy and develop the western wilderness, ignoring any interests which the aboriginal inhabitants of the area might have. One of the corporate sponsors of manifest destiny was the railroad. If the West was to be developed, then the railroads would have to connect them to American and global markets. The railroads lobbied Congress to obtain favored status and superior rights.

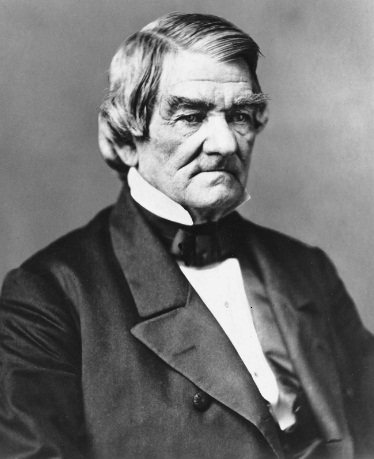

Cherokee chief John Ross had been a Union supporter during the Civil War and had spent much of the war in Washington, D.C. In spite of Ross’s personal charisma and his influence among government officials, a new treaty was imposed upon the Cherokee. When John Ross died in Washington in 1866, his nephew Will Ross was named principal chief to fill the unexpired term of his uncle. John Ross had groomed him for this position and had paid for his education at Princeton, where he had graduated with honors at the top of his class. With regard to the new treaty with the United States, Will Ross said:

“Whatever may be our opinion as to the justice and wisdom of some of the stipulations it imposes, we have full assurance that the delegation obtained the most favorable terms they could, and it is our duty to comply in good faith with all its provisions.”

However, Chief Ross indicated that there were some troublesome articles in the treaty. One of these, Article 11, granted a right of way through Cherokee land for a railroad.

In addition to forcing the Cherokee to grant a railroad right-of-way through their territory, the federal government required the same of the other nations. In the 1866 treaty imposed upon the Creek, for example, the treaty called for the Creek to give up rights-of-way for two railroads: one north-south and one east-west.

In order to take advantage of manifest destiny, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad was incorporated in 1870. It was generally called the K-T, which soon became the Katy. The newly formed railroad soon crossed the border into Cherokee territory and then veered southwest into the Creek Nation, the Choctaw Nation, and the Chickasaw Nation. This opened the way for the corporate invasion of Indian lands that would divest the tribes of their natural resources, land, and sovereignty. The Katy did not pay for its right-of-way. It also had an exemption from taxes and it bought raw materials from individuals in direct violation of tribal laws. In other words, the Katy ran roughshod over the Indian nations, seeking to extract as much wealth as it could while giving as little as possible in return.

In building the railroad, the steel rails had to be imported, but the ties upon which they rested could be obtained locally. The cedar forests which were abundant in Indian Territory seemed to be ideal for the ties. The railroad construction used up 2,700 ties per mile which resulted in much deforestation. Both the Choctaw and Chickasaw governments passed legislation to limit the exploitation of tribal resources to its tribal members. While many tribal members cut timber for the railroads, there was a great deal of poaching by non-Indians. Since the tribal courts had no jurisdiction over non-Indians, there was little that the Indian nations could do to enforce laws that regulated timber cutting.

Like other corporate interests of the time, the Katy felt that it was wrong for “unproductive” Indians to claim a rich and productive land while there were thousands of non-Indians who would be willing to take over the land and “develop” it. Of course, these non-Indians would make better use of the resources and in doing so would have to use the railroad’s services. In order to discourage Indian development, the Katy often refused to carry Indian freight and to stop at Indian towns.

In 1870, the first of a series of intertribal meetings known as the Okulgee Convention was held. Delegates from many Indian nations attended: Creek, Cherokee, Seminole, Ottawa, Eastern Shawnee, Quapaw, Seneca, Wyandotte, Peoria, Sac and Fox, Wea, Osage, and Absentee Shawnee. The delegates drew up a memorial to President Ulysses S. Grant, asking him to uphold the treaties of 1866-1867, to prevent the creation of a territorial government, and to deny access to the territory to any new railroads.

In 1871, Cherokee entrepreneur E.C. Bodinot, knowing where the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas (Katy) and the Atlantic and Pacific (A & P) railroads would intersect in the Cherokee Nation, constructed a hotel at the site. He then staked off the rest of the land into lots and named the new town Vinita. However, Boudinot’s actions were illegal under Cherokee law. Cherokee law at this time decreed that all land within one square mile of any railroad station was under the control of the Cherokee Nation. No one could make improvements on it without authorization from the Cherokee government. The Cherokee, in order to avoid a legal battle with Boudinot, convinced the A & P to move the intersection three miles north. In response Boudinot moved his hotel, and the new town of Vinita, north to the new site. The hotel, a two-story building, was named the Railroad Hotel.

In 1871, the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad built an illegal rail line through Choctaw territory in order to obtain coal.

In 1872, the Katy was completed through Creek territory. The completion of the railroad connected the Creek nation economically with the outside world. This encouraged more non-Indian agricultural settlement.

By 1876, railroads were often touted as important for economic development of the tribes and the tribes were encouraged to provide economic support for the railroads passing through their lands. In Oklahoma, however, the Cherokee found that passengers were being charged 12 cents a mile in their nation as compared with 3-4 cents in the neighboring off-reservation states. Freight rates on the reservation were high and in some instances the train would not stop on the reservation to even pick up the mail. When the tribes complained about this lack of service, the railroad lobbyists simply used this to bolster their case that so long as the tribes remained, profitable corporate enterprise would not be possible.

The Choctaw appointed a tax collector to exercise their right as a sovereign nation to tax the railroad. If the Choctaw had the power to grant rights-of-way, they reasoned, then they should have the power to tax the railroads. The Katy ignored this.

One of the lobbyists for the railroads was Elias Boudinot, a Cherokee from a prominent family. In 1879 he published an article in the Chicago Times that identified 14 million acres of Indian Territory as available for homesteading. This was land that had been set aside for the future settlement of Indians and had not yet been utilized. Boudinot’s article was widely republished in neighboring states. The Secretary of the Interior was soon receiving inquiries about homesteading the land. In addition, prospective settlers began camping out along the borders. Army patrols attempted to keep the intruders out. The Secretary of the Interior hinted to the tribes that the federal government might not be able to stem the tide of non-Indian settlement and advised them to give up holding land in common. They should instead prepare for the inevitable arrival of the homesteaders.

Alarmed at the pressure being exerted by the railroads to open up Indian country in Oklahoma, a group of non-Indian women in the east gathered signatures on a petition. In 1880 they presented a roll of signatures more than 300 feet long to President Rutherford Hayes and to Congress. They then gathered more than 100,000 signatures on a second petition.

In 1882, Congress granted a railroad a right-of-way through the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory, thus setting the precedent that Congress might authorize corporations to exercise privileges upon Indian lands without consulting the tribes.

Overall, all of the railroads, and particularly the Katy, in Indian Territory set the stage for the destruction of tribal governments, the loss of Indian land and resources, and the increase in poverty among Indians. It shows that corporate interests, at least during the late nineteenth century, were greater than those of either the Indian people (most of whom could not vote) and the sovereign Indian nations for whom the United States had a fiduciary responsibility.

Leave a Reply