Kevin Killer is a former state legislator in South Dakota and a senior fellow at Prism.

Kevin Killer is a former state legislator in South Dakota and a senior fellow at Prism.

Hau Mitakuyapi! (Hello my relatives!)

Please allow me to introduce myself as a new Prism fellow. I recently completed 10 years in the South Dakota legislature and have been in politics for the past 14 years. In the majority of these positions, I was tasked to work with Native American communities in South Dakota. These assignments provide a unique insight into how our Native nations worked with various levels of government.

Over this time, I saw the lack of Native representation as a disadvantage to being fully represented at all levels of government. I know now that despite non-Native allies’ intentions to support our communities, there was systemic inequity that prevented our full participation at all levels of government. That included not being able to participate in county elections in South Dakota until the late 1970s.

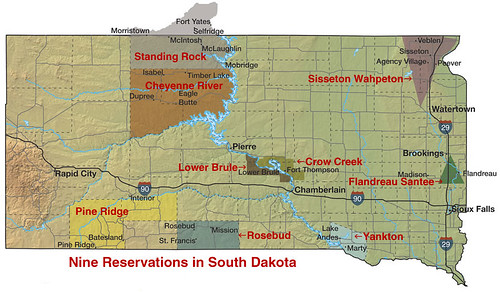

My involvement started in 2002 with former U.S. Sen. Tim Johnson’s reelection efforts. I helped my adopted dad go around the state of South Dakota and turn out the Native vote on three separate reservations in the middle of a blizzard. This campaign was one of the very few times in the history of South Dakota politics that turnout in Lakota/Dakota communities was a priority to victory.

Because turnout in Native communities was a priority in the election, Sen. Johnson went on to win. In 2004, because of the successful efforts in 2002, there was an even bigger commitment to turning out the Native vote for U.S. Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle’s reelection campaign.

I was hired as a field organizer working on Pine Ridge to focus on voter registration and turnout. Our community was excited to make history again, and we had an even better turnout that election. To our disappointment, however, it wasn’t enough to overcome the lead from the eastern side of South Dakota. We had some amazing people supporting us in Pine Ridge in the lead-up to Election Day, including Denis McDonough, Phil Schiliro, and other members of Sen. Daschle’s staff who went on to serve in President Obama’s administration.

Witnessing the amount of work and people needed to support campaigns was overwhelming, but at the same time, it provided the insight to know what our community would need to run our own community members for office.

Looking at what was possible, I thought it would be amazing and motivating to have all-Native representation within our state legislative district, especially after a court decision on Sept. 15, 2004, ruled that our legislative district was unfairly packed, with the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Indian reservations making up one supermajority minority district.

Alfred Bone Shirt, along with other tribal members, filed a lawsuit in late 2001 to seek a fairer district that could have Natives elected from these areas. Both tribal governments sent letters to the court asking for the ability to elect tribal members from each reservation to legislative seats. This opened the door for Natives to have their issues not only heard but represented by our own tribal members in state government. We had representatives before this lawsuit, but this would allow us to have more representation.

The next part was to find people who not only were willing to run, but also were willing to set aside three months of their lives each year—for just $6,000 in compensation—to serve in office. I asked a lot of people to consider it, but no one was interested, or they would tell me I should run. I decided to do it and ultimately served in our state House of Representatives for eight years and Senate for two years.

I went into office with optimism and some naïveté that, at 29, my presence would help. Being a Democrat in a conservative state, though, was a reality check I both was and wasn’t prepared for. The Native influence had been little to nil because, historically, it wasn’t politically convenient to be identified as Native American.

A good example of this was when I was new to the Judiciary Committee. It was one of the assignments I requested, and I was thankful to our legislative leadership for placing me on such a prestigious committee. Native American incarceration rates in South Dakota have mirrored African American male rates in many states, but without the national exposure. This disparity and other legal issues Natives have to face compelled me to ask for this committee assignment.

Being a non-attorney on the committee was a steep learning curve that helped me become a better committee member by asking questions and learning the legal language and the process behind legislation that eventually becomes law. What I brought to the committee was firsthand experience of what tribal members experienced living in a hybrid rural/reservation economy that experienced some of the highest generational unemployment rates in the country.

I often had to explain to my legislative colleagues that before South Dakota was recognized as a state in 1889, our communities had a 100% employment rate, and our life expectancy was most likely the highest in the region thanks to our healthy lifestyles and activity. Even with this truth, it was for the most part an uphill battle to overcome the implicit and historical biases that existed within the legislature to pass meaningful legislation that helped or changed the perception of our tribal communities.

At the time, I didn’t see a clear opportunity to help change the way our Native Nations were perceived within the legislature. That changed with HB 1104. The goal of the legislation was to prevent anyone over the age of 35 from filing a lawsuit against alleged perpetrators of sexual abuse who taught at or were a part of the administration of off-reservation boarding schools that were set up across the country in the late 19th and mid-20th century. It was a U.S. government mandate that forced Native children to attend these schools with the philosophy, as one of the founding officers at these schools put it, to “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Listening to the firsthand accounts of our elders who came to testify against this bill was difficult enough because the majority who appeared would’ve been around my grandparents’ age. What made it worse was the fact they only had a few minutes each to share their truth. What they didn’t get from this legislative process was any type of reconciliation or healing—only more hurt.

This was the realization: that the need to have their truths heard and recognized, the leadership that had been instilled in many of these elders, was critical to healing. Generations of our elders have unhealed trauma that would eventually manifest itself in unhealthy ways within our communities.

Over the course of this fellowship year, I want to look more into this process and share the positive steps being made by Native communities nationwide. It is an exciting time for many of the young people in our communities, but we need to educate this very well-informed generation about the realities we faced, along with our parents and grandparents.

Breaking the cycle of hurt must be the ultimate outcome of these efforts. I believe Native communities are at a turning point in their own healing.

Pilamaya (Thank you), Kevin Killer

Kevin Killer is co-founder of Advance Native Political Leadership, a former member of the South Dakota state Senate and House of Representatives, and a senior fellow at Prism.

Leave a Reply