One of the characteristics of American culture is an obsession with private property. The idea of holding land in common, as was the practice of Indian nations, was seen as uncivilized, un-Christian, and a barrier to civilization. The policies of the American government with regard to Indian nations were generally based on socioreligious concepts rather than on reality and fact-based information.

During the nineteenth century, Indians were first encouraged and then required to obtain individual ownership of land. The idea of owning land in severalty became almost an obsession of the late nineteenth century Christian reformers. They were convinced that such a policy would force the Indians to become more American. In his book The Dawes Commission and the Allotment of the Five Civilized Tribes, 1893-1914, Kent Carter writes:

“It became an article of faith among self-proclaimed friends of the Indians that the private ownership of property was one of the most powerful tools that could be used to bring about assimilation. They were determined to pressure the federal government into adopting a policy that would destroy tribal governments based on communal ownership of land and give each Indian his or her own piece of real estate.”

In reality, this was a policy intended to transfer wealth in the form of land from the poor to the wealthy, that is, from Indians to non-Indians.

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act—commonly called the Dawes Act after its main architect, Henry Dawes—which called for breaking up reservations into small parcels for each tribal member and the sale of surplus lands to non-Indians. The idea of the Dawes Act is to break up the reservations by giving each Indian family an allotment of land, similar to the homesteads given to non-Indian settlers. Anthropologist Clark Wissler, in his 1938 book Red Man Reservations, describes it this way:

“The hope was that to each head of a family could be allotted the land upon which he built his cabin, to which he would eventually be given title and thus the reservation pass into history, leaving in its wake new United States citizens of Indian ancestry.”

At the time the Dawes Act was passed, allotment was not a new concept for the administration of Indian reservations: the Commissioner of Indian Affairs had already made 7,673 allotments. In his book The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980, E. A. Schwartz reports:

“The allotment process mandated by the Dawes Act differed from earlier approaches in being compulsory, at the discretion of the president, and providing a process for reduction of Indian lands through negotiation for government acquisition of so-called surplus land remaining after allotment.”

The so-called Jeffersonian vision of America as a nation of small farmers composed of a family home surrounded by a few acres of farm land had never been realistic and by the late nineteenth century it was more fantasy than reality. At this time, the United States was no longer an agricultural economy. In her chapter in Dimensions of Native America: The Contact Zone, Marie Watkins writes:

“America, however, was no longer an agrarian nation, and big business, mass production and commercialism were the order of the day, making farming an unlikely road to financial success.”

The ideal of the family farm as economically viable was not realistic, but that did not stop government planners in Washington, D.C. from imposing their fantasy on the western American Indians. E. A. Schwartz reports:

“The philosophy behind the Dawes Act was a near-mystical belief in the efficacy of private property ownership, which was expected by some to erase the differences between white and Indian people and to lead, at last, to the assimilation of Indians into American society.”

In general, most Indians opposed the idea of allotment, but their opinions were not sought. Senator Henry Dawes, the principal author of the Allotment Act, believed that any Indian opposition to allotment was unreasonable and “wrongheaded.” Therefore, it was the duty—some say the Christian duty—of the government to get Indians to acknowledge the superiority of allotment by imposing it upon them.

Far away from the capital in Washington, the non-Indians along the coast of Oregon had a slightly different philosophy regarding the allotment of Indian reservations: this philosophy was based on two of the main aspects of American culture, greed and racism. The concern for non-Indians living near the Siletz Reservation, or illegally on the Siletz Reservation, was to obtain the Indian land for themselves so that they could then “develop” it and use it to make their fortunes. There was no concern for allotment as an Indian economic development program.

The Coast Reservation, or Siletz Reservation, was established in 1855 by executive order of President Franklin Pierce. The new reservation ran approximately 102 miles north and south along the Central Oregon coast. The land selected for this reservation was generally felt to be unsuitable for farming and thus less desirable for non-Indians. The establishment of this reservation set in motion the relocation of several different American Indian groups in Southern Oregon and Northern California.

Almost immediately, non-Indians in Oregon began lobbying to have the size of the reservation reduced and a number of non-Indians simply squatted on reservation land knowing that eventually they would be given title to the land. By 1870, the squatters were pressuring Congress to remove more land from the reservation and to open it up for non-Indian settlement. They circulated a petition demanding that the reservation be closed. The Indian agent for the reservation proposed dividing the Siletz Reservation into twenty-acre parcels which would be distributed to the Indian families. This would allow the Indians to keep about 5% of the reservation and allow the rest to be opened for non-Indian settlement.

Shortly after the passage of the Dawes Act, a special Indian Service agent began work on the allotment of the Siletz Reservation. E. A. Schwartz reports:

“Effects of allotment on the Siletz Reservation would include a drop in crop production and a radical reduction in the size of the reservation, followed by the loss of much of the land that had been allotted.”

In 1892, the reservation was divided into 80-acre parcels under the General Allotment Act. Many of the 551 individuals receiving allotments had to sell their land to satisfy debts and taxes.

The allotment process allowed for the government to negotiate for the sale of any reservation lands which had not been allotted. In 1892, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs sent a three-man commission to negotiate for the sale of lands not allotted on the Siletz Reservation. While the commission was told not to exert any undue influence on the Indians, the Indians were told that if they kept their lands they should not expect much in return. The leaders of the Siletz tribes, well aware that the United States had rarely kept its promises about making payments to Indians, demanded “cash in hand” for their land. Siletz leader George Harney explained to the commission that the people wanted to have their money before they died. The commissioners responded by explaining that the government does not pay cash.

At a second meeting with the commissioners, Siletz leader Charles Depoe expressed concern that any agreement reached could be changed by Congress without consulting with the Indians. Charles Depoe told them:

“May be we make a bargain here to-day and may be it won’t stay.”

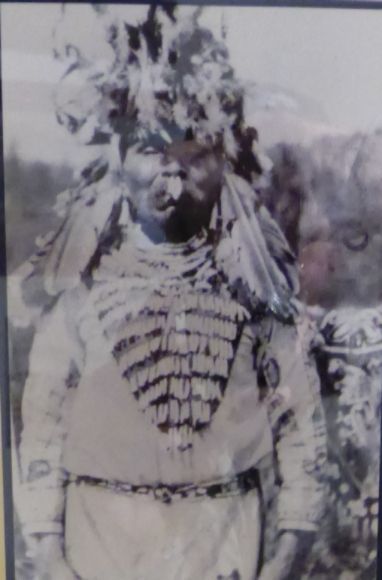

Shown above is Depot Charlie, also known as Charlie DePoe and Charles Depoe. This photo is on display in the Burrows House Museum in Newport, Oregon.

Shown above is Depot Charlie, also known as Charlie DePoe and Charles Depoe. This photo is on display in the Burrows House Museum in Newport, Oregon.

At the general council, seven men, including George Harney and Charles Depoe, were selected to negotiate with the commission. The Siletz committee initially demanded $175,000 for the surplus land with a payment of $100 paid to each person in cash. They finally agreed to $142,600 with $75 in cash to each person. According to the agreement, $100,000 would be in an interest-bearing fund and the interest from this fund would be divided among tribal members annually. The remaining $42,600 would be paid out to tribal members in annual installments of $75.

E. A. Schwartz writes:

“Why did they sell the surplus land? Aside from the likelihood that they needed the money, they knew that during the past thirty years the government had taken most of the original reservation without paying them a penny for the land. Now the government was willing to pay for what it had never clearly conceded to them in the past.”

Congress approved the agreement in 1894 and in 1895, reservation lands not allotted were opened to non-Indian settlement. In selling the lands to the public, the government made a profit of $120,000.

While the philosophy behind the Dawes Act claims that by forcing Indians to become self-sufficient farmers would enable them to fuller assimilate into American culture and lose their Indian identity, farming was not a realistic goal on the Siletz Reservation. E. A. Schwartz reports:

“Not even the most optimistic of the agents who managed the reservation had ever claimed that it contained such a quantity of farmland. The application of the Dawes Act on the Siletz obviously had little, if anything, to do with the idea that allotment would encourage farming.”

The political mythology of the Dawes Act was clearly not based on reality.

Leave a Reply