By 1870, it was clearly evident that the Indian Service was the most corrupt branch of the federal government and that Indian reservations were often being run for the financial benefit of the government-appointed Indian agents at the expense of the Indians. In order for Indians to fully assimilate into American society, it was felt that they had to be English-speaking, Christian farmers. Thus, government policy supported Christian missionary efforts on the reservations. In order to clean up the corruption of the Indian Service and the administration of Indian reservations, President Ulysses Grant proposed turning the administration of the reservations over to Christian missionary groups.

In his 1870 message to Congress, President Ulysses Grant explained that he was–

“determined to give all the agencies to such religious denominations as had heretofore established missionaries among the Indians, and perhaps to some other denominations who would undertake the work on the same terms – i.e. as missionary work.”

In accordance with President Ulysses S. Grant’s new policy, commonly known as the Peace Policy, the Secretary of the Interior allocated 80 reservations among 13 Christian denominations.

In 1871, the Methodist Episcopal Church was given jurisdiction over the Siletz Reservation in Oregon and Joel Palmer was appointed as Indian Agent. General Joel Palmer had been a Quaker, and he converted to Methodism so that he could become the Indian agent for the Siletz Indian Reservation.

The Coast or Siletz Reservation had been established in 1855 by executive order of President Franklin Pierce. The reservation had been established for 27 Indian tribes whose original territories ranged from southern Washington to northern California.

Many of the reservation Indians had taken up European-style farming. However, several families would settle together in a small village and then communally farm a fairly large parcel. This type of farming, similar in many respects to the corporate farming which dominated the American agricultural economy, often produced a surplus which could then be sold to non-Indians. While this type of farming worked economically, it did not fit the political and religious ideology of government administrators and missionaries who felt strongly that Indians must have small individual farms and live in isolated farmhouses.

Soon after becoming Indian Agent, Joel Palmer attempted to divide the Siletz Reservation into twenty-acre parcels which would be distributed to the Indian families. This would allow the Indians to keep about 5% of the reservation and allow the rest to be opened for non-Indian settlement. In his book The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980, E. A. Schwartz reports:

“…Palmer’s plan would probably have allotted practically all the genuinely useful farming and grazing land for Indian use. But it would have trapped the Indian people forever on small parcels of land, surrounded by white-owned properties, perhaps cut off from hunting and fishing sites.”

Palmer’s administration of the reservation was opposed by other Christians who felt that he wasn’t doing enough to force the Indians to become Christians. In 1872, Joel Palmer resigned, but remained on the reservation waiting for his replacement to be appointed.

While the policies of the United States required that Indians become Christians, there were some indigenous Indian revitalization movements in Oregon and California during the 1870s. One of these was known as the Ghost Dance, which was based on the 1869 vision of Wodziwob, a Paiute prophet. The Ghost Dance spread quickly among the different Indian nations of California and Oregon.

In 1871, two prominent leaders from the Siletz Reservation, Sixes George and Depot Charlie, learned about the Ghost Dance from people from the Grand Ronde Reservation. One of the men involved in the Ghost Dance on the Siletz Reservation, Coquille Thompson, would later recall that people began–

“…dreaming and getting excited. About a hundred old ladies danced like young girls. It was so crowded in the dance house that you could hardly walk in.”

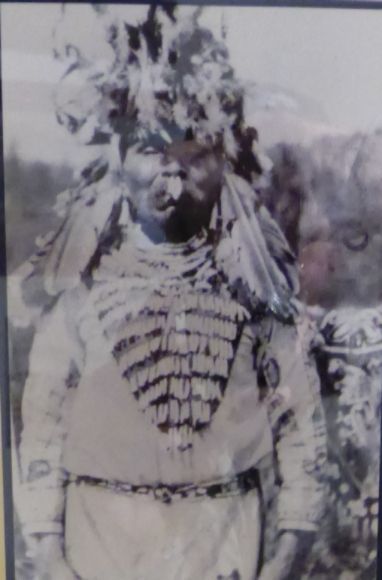

Shown above is Depot Charlie, also known as Charlie DePoe. This photograph is on display in the Burrows House Museum in Newport, Oregon.

Shown above is Depot Charlie, also known as Charlie DePoe. This photograph is on display in the Burrows House Museum in Newport, Oregon.

While local non-Indians were alarmed at the new religious movement and feared that it would lead to an Indian uprising, in 1873 both the Superintendent of Indian Affairs and Joel Palmer, who was still waiting for his replacement, reported that the people had no warlike intentions.

In 1873, another indigenous revitalization movement known as the Warm House Dance came to the Siletz Reservation. The new religion was brought to Oregon from California by Bogus Tom, Peter, and Mollie. Three dance houses were built on the reservation. Coquille Thompson would later recall:

“The old people danced hard, but the young ones didn’t join in much because they didn’t believe. The dance was kept up maybe twenty years, then the old people died off. The dance houses just rotted away.”

In the 1870s, non-Indians who were illegally living on reservation land were demanding the removal of the Indians from the reservation or from portions of the reservation. In 1873, Superintendent T. B. Odeneal recommended that Indians be removed from the land north of the Salmon River on the Siletz Reservation. He also recommended that Indians be removed from the southern portion of the Alsea portion of the reservation. He claimed that the removals had been requested by non-Indians in the area. E. A. Schwartz reports:

“Anyone living south of the Alsea River, six miles north of the subagency, was squatting on reservation land. Ordenal should have been concerned with evicting them, not satisfying their demands.”

In response to the removal request, Indian Service inspector Edward C. Kemble was sent to the reservation. He held a council with the Indians. George Harney, the head chief of the confederated tribes, told him:

“We were driven here, and now this is our home, and we want to stay.”

Tututni chief William Strong told Kemble that he would stay even if the soldiers came to evict him:

“If they want to hang me they can do so, but I will not leave.”

In 1874, one of the Oregon senators, John Hipple Mitchell, complained to the Secretary of the Interior that the Indian people on the Siletz and Alsea reservations were taking up over 1,400 square miles of land and thus excluding non-Indian settlement. Three chiefs from the Alsea Reservation met with the Indian agent and expressed their desire to remain in their homeland. The agent reported:

“These Indians have never received much from the Government and now do not ask anything but the privilege of living and dying in the country the Government had once given them as their own.”

Senator Mitchell, described by some historians as “a man of dubious integrity,” seemed to have been concerned with the millions of board feet of valuable timber on reservation land which could be harvested and shipped to San Francisco.

In 1875, in a cost-cutting move, Congress closed the Alsea Reservation and the northern part of the Siletz Reservation. Skeptical Senators inserted a clause which required that the Indians give their consent for the closure. While the Indian people declined to consent, the Indian agent simply claimed that they had, in fact, indicated a willingness to consent to the closure and a federal commissioner certified their agreement.

The reduction of the reservation means that reservation lands were to be opened to non-Indian settlement and that the Indians who had been living in the reduced area would have to move. Tillamook chief Joseph Duncan protested his tribe’s removal:

“We all want to stay in our own country and take up land like the whites—Our people all think alike on this subject.”

The agent told them that the American settlers would cheat them if they took up homesteads and recommended that they move. The Nestucca also insisted that they would rather take their own land under the homestead law than be removed.

Alsea chief Albert told the agent:

“We have houses which we built ourselves—have little farms and places, and we do not want to give them up even if our land is not fenced.”

Alsea chief William said:

“Never have we done wrong to the whites—Never have we killed a White man—Why do the Whites have sick hearts for our land?”

The arguments made no impression on the agent.

The agent called a council with the Indians. Three leaders from the Siletz Reservation—George Harney, Depot Charlie, and William Strong—were hand-picked by the agent and supposed to speak in favor of removal. The Indians were told that they could stay on the reservation by taking 20-acre homesteads which were being surveyed for them. After the council, the three Siletz men were supposed to have informed the agent of the Indians’ willingness to be removed. Historian E. A. Schwartz, in an article in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, reports:

“The statements attributed to unnamed Alsea Reservation people at the mouth of the Alsea by Harney, Depoe, and Strong were the only ‘consent’ ever given for removal.”

In 1877, the Alsea band was moved north to Yaquina Bay near Newport. They were supposed to have been moved farther north to the Salmon River, but the government did not have sufficient funds to complete the move. At Yaquina Bay, the Alsea starved and, while many observers reported that Indians were dying of starvation, the government denied that hunger was a problem.

In 1879, Humbug Jim brought the Big Head dance to the Siletz Reservation. The dance, which originated at the Round Valley Reservation in California, was similar to the Warm House dance.

In 1879, the Methodist Board of Missions recommended Edmund Swan as the new Indian Agent. Swan resisted efforts by non-Indians in the area to open the reservation up for more development. In response, Senator James Slate of Oregon introduced legislation to remove the Siletz Indians to an out of state reservation, or to the Grand Ronde Reservation if there was no out of state location available for them.

Under Methodist rule, the primary qualification for employment at the Siletz agency was to be a Methodist. By 1880, Edmund Swan was complaining about this requirement. E. A. Schwartz reports:

“Swan’s experience with the Methodists suggests that the policy of church involvement, rather than replacing political corruption with churchly uprightness, gave scope to the corrupt impulses within the churches.”

In 1883, Swan was replaced because he had annoyed local Methodists. The Oregon Methodist Episcopal Conference recommended F. M Wadsworth as his replacement. Wadsworth became the last of the church-appointed Indian agents as the federal government abandoned its practice of turning over reservations to Christian missionary groups.

Leave a Reply