In major museums, only a small fraction of the artifacts held by the museum are on display and interpreted for the public. Most of the museum’s artifacts are in vaults where they are available only to researchers. The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History maintains a Visible Vault in which visitors can view hundreds of archaeological artifacts. The Visible Vault includes archaeological treasures from Ancient South America, the Peruvian cultures that flourished prior to the Inka.

The Visible Vault

According to the Museum display:

“We have selected some objects to feature on exhibition-quality mounts, but most of the six hundred items are displayed in storage mounts that use archival materials ideal for long-term storage. The white band around some of the artifacts is unbleached cotton twill tape that is often used to secure objects in case of an earthquake. We invited you to explore the selected highlights of this rich collection while taking a rare look at how these objects are cared for behind the scenes.”

The Visible Vault functions as a working storeroom for the museum’s archaeological collections and therefore the majority of the objects which can be seen do not have any form of description or interpretation.

The Inka Empire

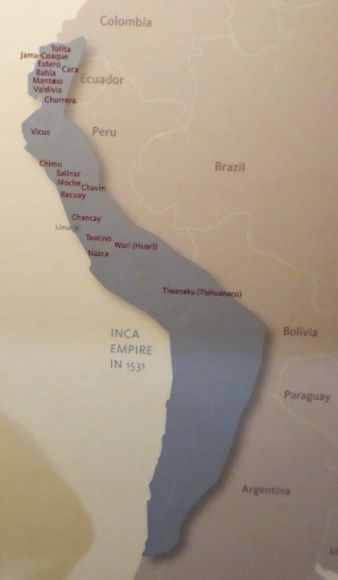

When the Spanish under the leadership of Francisco Pizarro arrived in Peru in 1532, they encountered the Inka (also spelled as Inca) empire. With a population of about 8 million people occupying the area from the Ecuador-Colombia border in the north to central Chile in the south, the Inka empire was the largest indigenous empire in the Americas.

The shaded area shows the extent of the Inka Empire in 1531.

The shaded area shows the extent of the Inka Empire in 1531.

The Inka empire in 1532 was less than a century old. The Quechua-speaking Inka began to coalesce as an identifiable people in the twelfth century in the area around Cuzco. They incorporated religious traditions from the earlier Wari and Tiwanaku civilizations. They began to expand about 1438 and by 1460 had become an empire.

The Inka empire expanded through a combination of military conquest, alliances, and negotiations. As an empire, the Inka ruled an amazing array of different peoples: peoples speaking different languages, inhabiting different environments, and having distinct ethnic traditions and identities. There were often large-scale transfers to conquered populations from one area to another, which broke up the indigenous populations and allowed the Inka to govern them with less resistance.

The Inka used a system of labor-based taxation, known as Mit’a. This enabled them to engage in large-scale building projects. It tied the commoners to the state during parts of the year. During these periods, they were fed and supported by the state. In some instances, this required travel from the home towns of the workers to distant building sites.

The Inka empire was tied together with an efficient road system which included 24,800 miles of roads. In an entry in The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Thomas Pozorski and Shelia Pozorski write:

“A good portion of this road system was built by earlier peoples, but the Incas successfully connected most disjointed segments into an integrated system.”

They did not have wheeled vehicles but relied on llamas and human porters to transport goods throughout the empire.

With regard to the Inka artifacts, the Museum display states:

“The Inca built on cultural traditions stretching back thousands of years to create an administrative, economic, political, and religious empire of almost unimaginable complexity. The objects on display here are characteristic of the Inca and their conquered peoples. They are emblematic of long-standing Andean traditions incorporated into Inca religion, economy, and statecraft during the 13th, 14th, and early 15th centuries.”

Chavin

Shown above is a Chavin style double-spout and bridge vessel. The Chavin period dates from 1000 BCE to 200 BCE.

Shown above is a Chavin style double-spout and bridge vessel. The Chavin period dates from 1000 BCE to 200 BCE.

Chavin is a site in the Mosna Valley in the north central highlands of Peru. This site was the center of one of the earliest widespread religions and art styles in the region. According to the Museum display:

“Chavin was one of the earliest artistic styles to spread across ancient Peru, probably arriving with trade goods and religious ideas. Chavin is known for its elaborate depictions of ferocious-looking birds, reptiles, and jaguars, often in anthropomorphized, or human, forms.”

In an entry in The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Thomas Pozorski and Shelia Pozorski write:

“The Chavin culture seems to be an amalgamation of ideas derived from earlier coastal, highland, and tropical forest cultures.”

Thomas Pozorski and Shelia Pozorski also write:

“The Chavin culture was perhaps the first widespread horizon style in Peru, but recent fieldwork points to more restricted areal extent for this culture than previously postulated.”

With regard to Chavin art, in their entry on Chavin culture in The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Shelia Pozorski and Thomas Pozorski write:

“The culture is noted for its art style centered around feline and other animal designs that feature grimacing mouths with interlocking canines and eyes with eccentric or pendant pupils.”

Moche

In an article in Archaeology, Jarrett Lobell writes:

“Rather than being a single political entity or state, the Moche culture was a loose system of chiefdoms situated in multiple irrigated valleys, linked by shared practices and common beliefs. Their territory encompassed more than 400 miles along the coast of southern Peru.”

Thomas Pozorski and Shelia Pozorski write:

“The Moche culture, which possessed a state organization is most noted for its superb modeled and bichromed painted pottery, decorated with scenes from aspects of Moche ritual life. The Moche people were also excellent metallurgists, working with copper, gold, and silver to craft hundreds of delicate pieces of jewelry and body ornaments that were used during ceremonies and subsequently buried with elite rulers when they died.”

In his entry on Moche culture in The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Jeffrey Quilter writes:

“Moche’s fame derives from outstanding craftsmanship, especially in ceramics and metalwork, as well as impressive flat-topped adobe pyramids arranged in groups with ramps, plazas, and other features.”

With regard to Moche pottery, Jarrett Lobell writes:

“Moche potters created evocative ceramics depicting daily life, the natural world, religious sacrifices, and deformed and even skeletal figures, as well as an extraordinary panoply of hybrid monsters, mythological creatures, and gods in many forms.”

Jeffrey Quilter also writes:

“The origins of Moche culture are uncertain, but they seem to have drawn upon Chavín traditions filtered through the Vicús, Salinar, and Gallinazo cultures.”

Shown above is a Moche llama effigy stirrup-spout bottle. The Moche flourished between 100 BCE and 600 CE.

Shown above is a Moche llama effigy stirrup-spout bottle. The Moche flourished between 100 BCE and 600 CE.

According to the Museum display:

“The Moche, famous for their royal tombs, are also know for their naturalistic portrait and effigy pottery. Using two-piece press molds, Moche potters created detailed and evocative vessels, like this somewhat sinister-looking llama carrying a load on its back.”

The demise of the Moche civilization seems to have been brought about by a Mega El Niño that brought 30 years of intense rain followed by 30 years of drought.

Chancay

Shown above is a human figure from the Chancay culture which flourished on Peru’s central coast about 1000 CE.

Shown above is a human figure from the Chancay culture which flourished on Peru’s central coast about 1000 CE.

Nazca

The Nazca (also spelled Nasca) were farmers who transformed the desert into farm lands where they were able to grow maize, squash, sweet potatoes, manioc, cotton, cocoa, and San Pedro cactus. They are known for their beautiful pottery, which includes vessels with double stirrups, animal and human forms, effigies, and a painting technique in which the pottery was painted before firing. Thomas Pozorski and Shelia Pozorski write:

“This culture is particularly noted for its fine polychromed pottery depicting mythological scenes and personages.”

Nazca was contemporaneous with Moche.

Shown above is a Nazca vessel. The Nazca flourished on Peru’s south coast between 100 BCE and 750 CE. Shown on this vessel is a “mythical being.”

Shown above is a Nazca vessel. The Nazca flourished on Peru’s south coast between 100 BCE and 750 CE. Shown on this vessel is a “mythical being.”  Shown above is a gold Nazca nose ornament.

Shown above is a gold Nazca nose ornament.

Ancient America

Highly developed civilizations existed in the Americas for thousands of years before the Europeans began their invasion.

Leave a Reply