The Cahuilla homeland in California was bounded on the north by the San Bernardino Mountains; on the south by the northern Borrego Desert; on the east by the Colorado Desert; on the west by the present-day city of Riverside. The designation Cahuilla is said to mean “masters” or “powerful ones.” As a tribal designation, Cahuilla is more of a linguistic designation than a governmental or political one: the many different Cahuilla villages tended to be autonomous and there was no single overall governmental structure which united them.

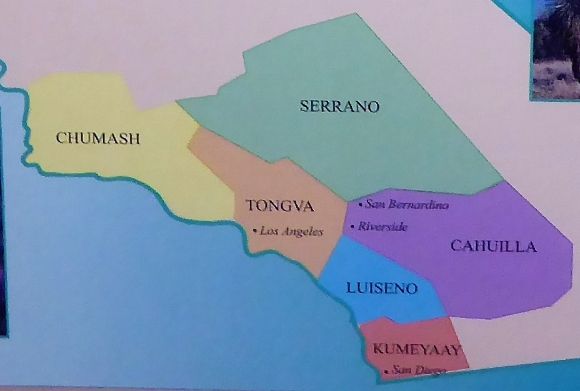

The map above shows the territories of the six Southern California Indian nations.

The map above shows the territories of the six Southern California Indian nations.

The Cahuilla Continuum was an exhibit at the Riverside Metropolitan Museum authored and curated by Sean C. Milanovich. The exhibit told the story of the Cahuilla from creation to the present day. One display in the exhibit focused on the Big Four: ámul (agave), tévat (pine nuts), qwínyily (acorn nuts) and ményikish (mesquite beans). These four were the traditional foods of the Cahuilla. According to the display:

“The Cahuilla developed a relationship with all things around them, especially the wéstern (plants). The land offered an abundance of natural resources. The Cahuilla had a deep understanding of the wéstern. Wéstern were living beings and there was communication between man and the wéstern. Múkat, the Creator, created wéstern for man to use as food, utilitarian objects, house structures and medicine.”

Agave (ámul) grows at elevations from 500 to 3,500 feet. It was traditionally harvested in March and April. Writing in 1900, David Prescott Barrows, in a report reprinted in The California Indians: A Source Book, reports:

“Most remarkable of all the plants that flourish in these wastes is the agave, perhaps the most unique and interesting plant of all America.”

The heads of the agave plant are cooked in earth ovens: large pits (náchishem) which are lined with stones. Fires are kept in the pits until the stones are hot, then the agave is placed in the pit, covered with dirt and grass, and allowed to roast for a day or two. Agave which is prepared this way is said to last for years.

Mesquite bean (ményikish) grows at elevations from 250 feet below sea level to 3,000 feet above sea level. David Prescott Barrows writes:

“The fruit of the algarroba or honey mesquite (Prosopis juliflora) is a beautiful legumen, four to seven inches long, which hangs in splendid clusters. A good crop will bend each branch almost to the ground, and as the fruit falls, pile the ground beneath the tree with a thick carpet of straw-colored pods. These are pulpy, sweet, and nutritious, affording food to stock as well as to man.”

Mesquite beans were traditionally harvested in June and July. For the Cahuilla, the mesquite tree was an important source of plant food. In the early summer, the mesquite blossoms would be roasted, formed into balls, and then stored for later consumption. Later in the year, the mesquite beans would be harvested. The mesquite beans were stored until needed and then processed using a milling stone. With regard to processing, David Prescott Barrows reports:

“The beans are never husked, but pod and all are pounded up into an imperfect meal in a wooden mortar.”

Shown above is a mortar (qáwvaxal) made about 1900. This mesquite mortar was used for pounding mesquite beans into flour.

Shown above is a mortar (qáwvaxal) made about 1900. This mesquite mortar was used for pounding mesquite beans into flour.

Pine nuts (tévat) grow at elevations of 2,500 to 9,000 feet. It was traditionally harvested in August and September. In harvesting pine nuts, the cones are beaten from the tree and roasted in a fire. The cones are then broken open and the nuts are harvested.

Acorn nuts (qwínyily) grow at elevations of 1,000 to 8,000 feet. It was traditionally harvested in October and November. Traditionally, the people gathered the acorns by climbing the tree and then beating off the nuts with a long slender pole. The acorns are ground in a mortar and then leached.

Food was stored in large basket granaries for use during the winter months.

The Cahuilla used solar, lunar, and stellar observations to predict the ripening of certain wild foods.

Shown above is a gathering basket (sáqwaval) made between 1890 and 1910. This basket shows no signs of having been used. It is decorated with eagles, lizards, bats, and other animals and plants.

Shown above is a gathering basket (sáqwaval) made between 1890 and 1910. This basket shows no signs of having been used. It is decorated with eagles, lizards, bats, and other animals and plants.  Shown above is a basket bowl (kávamal) made about 1900. This basket features a plant motif.

Shown above is a basket bowl (kávamal) made about 1900. This basket features a plant motif.  Shown above is a basket bowl (kávamal) made by Antonia Apapas Casero from the Cahuilla Reservation about 1930.

Shown above is a basket bowl (kávamal) made by Antonia Apapas Casero from the Cahuilla Reservation about 1930.  Shown above is a basket bowl (kávamal) made by Antonia Apapas Casero from the Cahuilla Reservation between 1920 and 1930.

Shown above is a basket bowl (kávamal) made by Antonia Apapas Casero from the Cahuilla Reservation between 1920 and 1930.  Shown above is an oval basket bowl (kávashmal) made about 1920. This basket features six agave plants and two human hand designs.

Shown above is an oval basket bowl (kávashmal) made about 1920. This basket features six agave plants and two human hand designs.  Shown above is a quail trap (láhmeah qáxal) made before 1910.

Shown above is a quail trap (láhmeah qáxal) made before 1910.

Leave a Reply