For more than 10,000 years Indian people have lived adjacent to the Columbia River. In the Columbia Gorge area, hundreds, if not thousands, of archaeological sites provide silent testimony to this long period of human occupation. Rock art, in the form of petroglyphs and pictographs, is found throughout the area. The area along the Columbia River from the present-day city of The Dalles to the confluence of the John Day River with the Columbia River contains one of the largest collections of rock art in North America. Archaeologists James Keyser, Michael Taylor, George Poetschat, and David Kaiser, in their book Visions in the Mist: The Rock Art of Celilo Falls, report:

“More than 100 individual rock art sites have been found and recorded in the area and others are discovered each year. The smallest of these are single images but the largest contain more than 1,000 different motifs.”

The rock art in this area includes both pictographs which are painted on stone, and petroglyphs which are pecked or carved into stone. Writing about the Columbia Plateau in North America, Keo Boreson, in his entry on rock in the Handbook of North American Indians, reports:

“These carved and painted images give an intimate glimpse into the lives of people that other archaeological remains do not, a visual memory that goes a step beyond the everyday necessities of food and shelter.”

Archaeologist James Keyser, in his book Indian Rock Art of the Columbia Plateau, writes:

“Pictographs are rock paintings. On the Columbia Plateau these are most often in red, but white, black, yellow, and even blue-green pigments were sometimes used.”

Due to the geological formation of the Columbia Gorge, there are extensive deposits of ochre in the area and this mineral was often used by Indian artists as a paint pigment. James Keyser writes:

“Early descriptions indicate that Indians mixed crushed mineral pigment with water or organic binding agents, such as blood, eggs, fat, plant juice, or urine, to make paint.”

The pigments were most frequently applied to the rock using fingers: most of the lines a finger-width. James Keyser writes:

“When freshly applied, the pigment actually stains the rock surface, seeping into microscopic pores by capillary action as natural weathering evaporates the water or organic binder with which the pigment was mixed. As a result, the pigment actually becomes part of the rock.”

With regard to location of pictographs in the Plateau area, Keo Boreson, in his entry on Rock Art in the Handbook of North American Indians, reports:

“Pictographs are often located in out-of-the way mountainous areas near rivers, lakes, springs, or streams. A few sites are at high elevations with a panoramic view of river valleys.”

Pictographs are often associated with personal vision quest sites and in some instances, they may serve as a way of recording the vision.

While most of the rock art sites in The Dalles-Deschutes area were inundated by the reservoir created by The Dalles Dam, there are still a number of rock art sites in the area. A trail from the Horsethief Lake unit of the Columbia Hills State Park in Washington leads up to some of these ancient pictograph sites. Because of concerns for vandalism, the trail is gated, and the pictographs can only be visited on a guided tour.

Shown above is the trail leading to the pictograph sites. People are only allowed into this area with a guide—there are two guided tours per week.

Shown above is the trail leading to the pictograph sites. People are only allowed into this area with a guide—there are two guided tours per week.  Another view of the trail.

Another view of the trail.

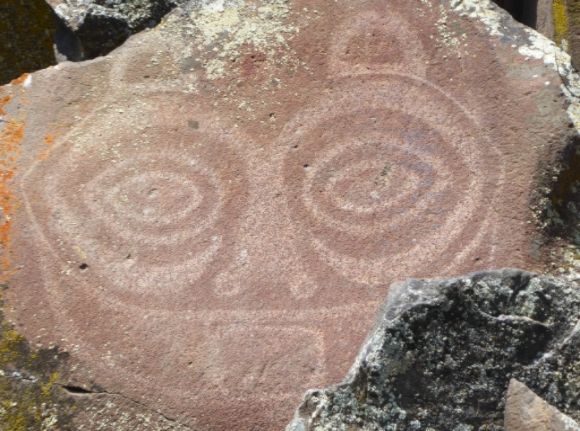

The image shown above is both a pictograph and a petroglyph

The image shown above is both a pictograph and a petroglyph

Shown above are the rock faces containing some of the sites.

Shown above are the rock faces containing some of the sites.

Many of the pictographs are faded and difficult to see with both the naked eye and ordinary cameras.

Many of the pictographs are faded and difficult to see with both the naked eye and ordinary cameras.

Many of the pictographs are fairly high in what seem to be places that would be difficult to access.

Many of the pictographs are fairly high in what seem to be places that would be difficult to access.

In her essay on rock art in Painters, Patrons, and Identity: Essays in Native American Art to Honor J.J. Brody, H. Denise Smith writes:

“Rock art is located a distance from a living or public space, remote and inaccessible, which is then interpreted to mean that such a place could have been the locus for ritual activities of a private or restrictive nature.”

The black marks on the right are not aboriginal but were made by someone who tried making rubbings with carbon paper.

The black marks on the right are not aboriginal but were made by someone who tried making rubbings with carbon paper.

Our guide explaining some of the pictographs. The guide is the one wearing the hat.

Our guide explaining some of the pictographs. The guide is the one wearing the hat.

A Note About Meaning

It is fairly common for non-Indians to speculate about the meaning of American Indian rock art. Some non-Indians view American Indian rock art as a kind of primitive writing and there are even some who claim to be able to “read” this writing even though they do not speak an Indian language. In his book The Serpent and the Sacred Fire: Fertility Images in Southwest Rock Art, Dennis Slifer writes:

“There is consensus among scholars that rock art is not ‘writing’ and cannot be ‘read’ as such. It is language only in the sense that symbols are used to represent things in a nonliteral, symbolic manner.”

Leave a Reply