The Pueblos are the village agriculturists of New Mexico and Northern Arizona. While the Pueblos are usually lumped together in both the anthropological and historical writings as though they are a single cultural group, they are linguistically and culturally divergent. The Pueblos speak six mutually unintelligible languages and occupy more than 30 villages in a rough crescent more than 400 miles in length.

Pueblo pottery is one of the best known American Indian art forms. For many centuries, Pueblo people have made and used a wide variety of pottery containers, including bowls, jars, cups, ladles, and canteens. In addition, Pueblo potters also produced figurines, effigy vessels to be used for religious purposes, pipes, and prayer meal bowls. The pottery is often highly decorated and traded throughout the region.

Pottery varies among the Pueblos according to differences in raw materials, technology, and aesthetics. Each of the Pueblos has its own distinctive decorative styles. In addition, within a Pueblo the work of a particular potter, or the potter’s family, can sometimes be recognized.

According to a display at the Portland Art Museum:

“Pottery is an art form that has existed in the Southwest for nearly two thousand years. Each Pueblo developed its own distinctive style of pottery and uses clay that is specific to that particular Pueblo. Once the clay is prepared and the temper is added a potter builds the vessel by adding row upon row of coils and molding it into shape by hand. After the desired shape is achieved and the surface is prepared the vessel is then painted with a yucca brush using pigments made from plants and minerals.”

In order to promote even drying and to minimize warping, temper is added to the clay. Temper may include sand, pulverized rocks, and ground potsherds. Temper varies according to region—and the type of clay and other materials available in the region—as well as to the personal preferences of the potter. In some areas, such as the Hopi mesas, sand naturally occurs in the mined clay and therefore the potters rarely need to add additional temper. At Taos and Picuris, the clay is naturally tempered with inclusive mica and the result is a very durable ware suited for cooking. At Zuni, the potters generally use ground potsherds: this means that pottery which might be hundreds of years old is incorporated into the new pottery. At Santo Domingo and Cochiti, volcanic tuff, usually called “sand” is used for temper, while at Zia and Santa Ana, potters use a water-worn sand.

Firing the pottery is a crucial step in Pueblo pottery. This is a process which takes about six hours. The process of firing the pottery is described by Rick Dillingham in his essay in I Am Here: Two Thousand Years of Southwest Indian Arts and Culture:

“The firing of pottery is a short process, taking only a few hours, but careful monitoring of the firing is exhausting and those hours are intense. The ware is stacked on grating, made from old pottery sherds and specially made pottery baffles, to allow for even air circulation and heating.”

In an article in American Indian Art, Hopi potter Karen Kahe Charley and anthropologist Lea McChesney report:

“Firing brings an artist’s inner thoughts and feelings, contributed with her breath to the formation of a new being through the long duration of her labor and now distilled within the pot’s interior, to the surface and sets them as the public feature of her work.”

Pueblo pottery since the later 1800s has become renowned as collectable art work and this has created some conflicts with traditional Pueblo culture. The collectors who buy Pueblo pottery, almost all of whom are non-Hopi, want to know who made the piece and therefore a signature on the pot is important to them. In an article in American Indian Art, Dwight Lanmon and Francis Harlow note:

“Traditional Pueblo culture views the individual as a vital part of the whole, and personal recognition has largely been shunned. This attitude changed slowly in the 1900s and recognition of the work of individual potters has now become commonplace.”

Shown below is some of the Pueblo pottery which is on display at the Portland Art Museum:

San Ildefonso

The native name for the Tewa-speaking pueblo of San Ildefonso is Pokwoge which means “where the water cuts down through.” The most famous San Ildefonso designs are the black-on-black designs pioneered by María and Julian Martinez. Rick Dillingham writes:

“The Black-on-black technique involves an initial overall polishing of the vessel with red slip. Then, using a thinned mixture of slip, designs are painted over the polished surface. Before the firing the jar is a matte red-brown on polished red, and after the firing the more recognizable matte and polished black.”

In 1921, María and Julián Martínez began to teach others in San Ildefonso Pueblo the method of making black-on-black pottery which developed into major industry for the Pueblo.

In 1923, potters María and Julián Martínez began to sign their work.

In 1933, San Ildefonso potters Maria and Julian Martinez received the Best in Show award at the Century of Progress, Chicago World’s Fair.

At San Ildefonso, the potters use a combination of geometric and curvilinear design elements, as well as bird and floral motifs.

Shown above is a bowl by María Martinez made about 1930-1940.

Shown above is a bowl by María Martinez made about 1930-1940.  Shown above is another view of her bowl.

Shown above is another view of her bowl.  Shown above is a bowl by María and Jose Martinez made about 1930.

Shown above is a bowl by María and Jose Martinez made about 1930.  Shown above is a bowl by María Martinez made about 1930-1940.

Shown above is a bowl by María Martinez made about 1930-1940.  Shown above is a bowl by María Martinez made about 1950-1960.

Shown above is a bowl by María Martinez made about 1950-1960.  Shown above is bowl made by an unidentified potter about 1910-1920.

Shown above is bowl made by an unidentified potter about 1910-1920.  Shown above is jar made by an unidentified potter about 1910-1920.

Shown above is jar made by an unidentified potter about 1910-1920.

Santa Clara

The native name for the Tewa-speaking pueblo of Santa Clara is Ka’po whose meaning is unknown. Carved black pottery was introduced at Santa Clara about 1924-1926 by Serafina Tafoya. Rick Dillingham writes:

“At the time it was first made it must have seemed quite innovative, but now it is mainstream traditional Santa Clara pottery.”

Shown above is a jar by Pablita Chavarria made about 1960.

Shown above is a jar by Pablita Chavarria made about 1960.

Zuni

The name Zuni is the Spanish corruption of the Keresan word Sunyi. The native name for the pueblo is A’shiwi which means “the flesh.” With regard to Zuni pottery designs, Rick Dillingham reports:

“The design most associated with Zuni is a semirealistic deer motif with a line leading from the heart to the mouth. This is most often called the ‘heart-line’ deer.”

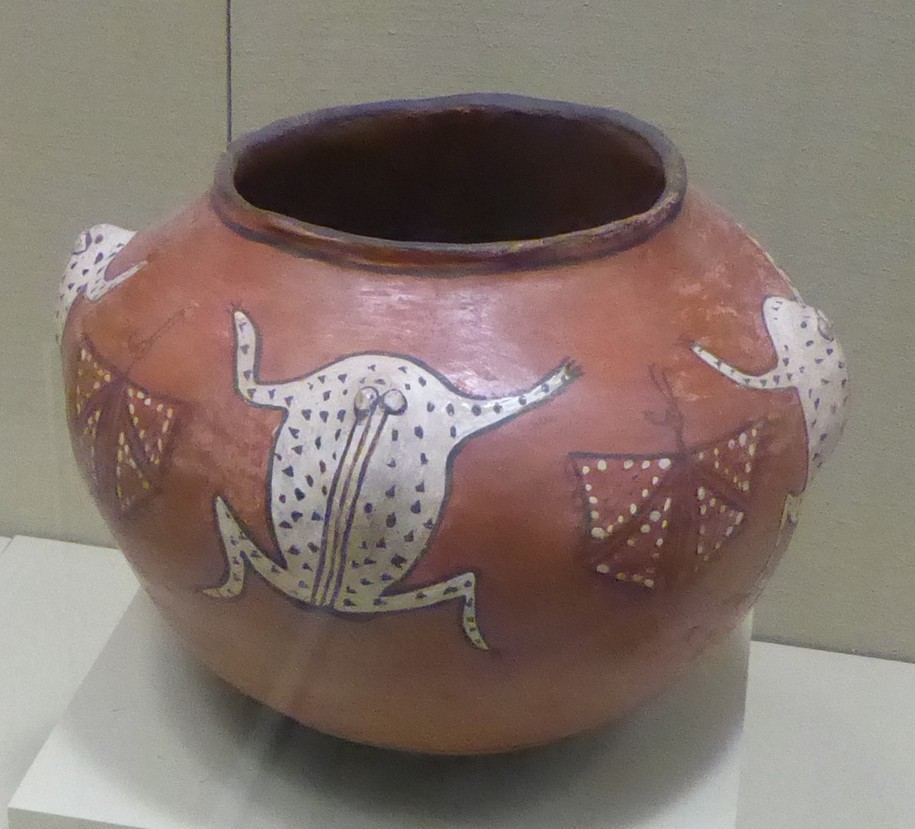

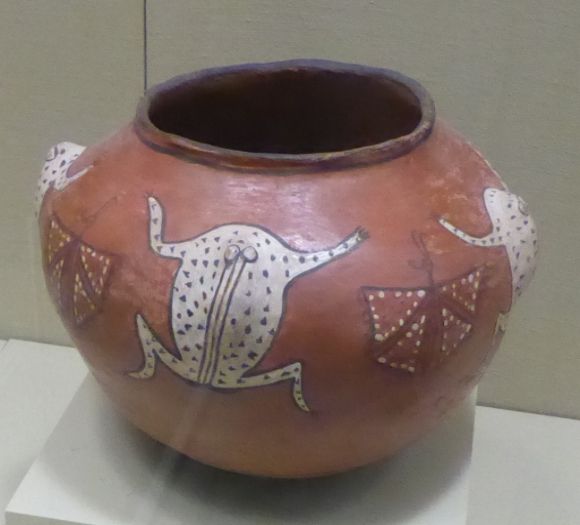

This bowl was made about 1920. Notice the heartline or lifeline in the figure of the deer.

This bowl was made about 1920. Notice the heartline or lifeline in the figure of the deer.  This canteen was made about 1890.

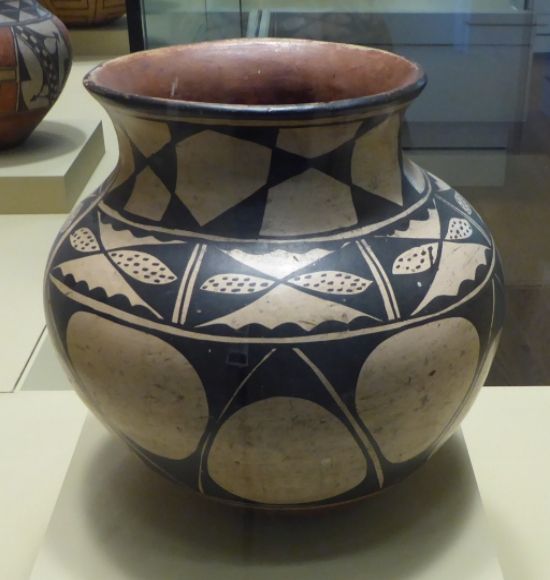

This canteen was made about 1890.  This jar was made about 1920.

This jar was made about 1920.

Zia

Zia pottery is distinctive because of the use of a ground basalt temper. With regard to design, Rick Dillingham reports:

“Zia pottery designs are very distinctive in the use of bird motifs and the undulating ‘rainbow’ band, encircling many jars with bird and floral motifs.”

Zia designs are sometimes similar to those used in Acoma and Laguna.

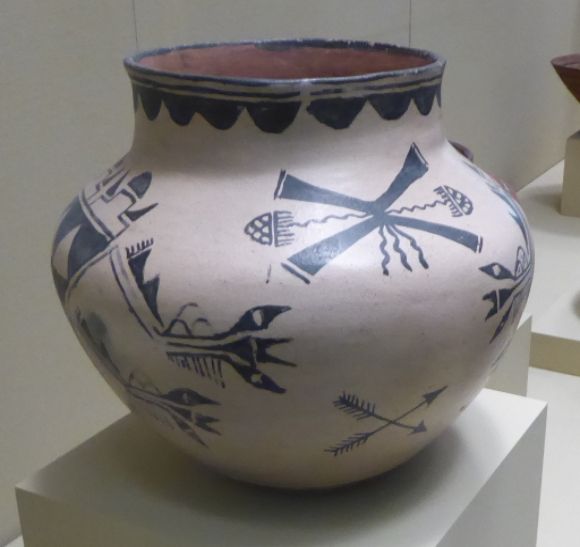

This jar was made about 1940-1950.

This jar was made about 1940-1950.

Santo Domingo

The native name for the Keresan-speaking pueblo of Santo Domingo is Kiuwa whose meaning is unknown. The designs used by Santo Domingo potters tend to be geometric, but include some bird and floral elements.

This bowl was made about 1920.

This bowl was made about 1920.

Cochiti

Cochiti designs often include free-floating elements and ceremonial motifs such as clouds and lightning. In his book Cochiti: A New Mexico Pueblo, Past and Present, Charles Lange reports:

“Cochití pottery has traditionally been black-on-cream, often combined with brick-red surfaces on the exterior bottoms and the complete interiors of bowls and ollas.”

This jar was made about 1930.

This jar was made about 1930.  This standing figure was made about 1910.

This standing figure was made about 1910.

Leave a Reply