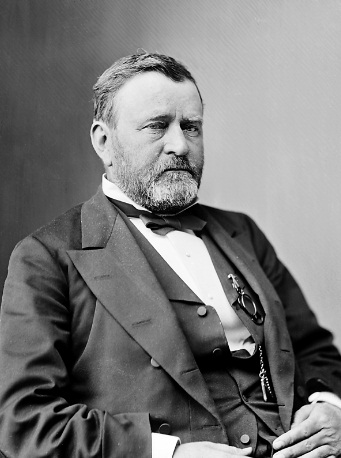

When Ulysses S. Grant became President of the United States in 1869, the Indian Office (also known as the Indian Service, and the Indian Bureau) was generally seen as the most corrupt branch of the American government. The Office of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior was headed by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, a political appointee. Administering the Indian policies of the government in the field were superintendents and agents, who were primarily political appointees and a few detached soldiers.

With regard to the agents and superintendents, William Roche, in his University of Montana M.A. Thesis The Territorial Governor as Ex-Officio Superintendent of Indian Affairs and the Decline of American-Indian Relations, reports:

“Oftentimes, the men in the field did not see a tribesman until they reached the seat of their respective superintendency or agency. Most appointments were based on no better qualifications than faithful party service.”

Since the field staff knew that their positions were temporary—dependent on the outcome of the next election—they often misused the office for personal gain in wealth and/or politics. In his section in The Native Americans: An Illustrated History, Peter Nabokov reports:

“On the reservation an agent could thrive as a tyrant, with no one to check his authority or scrutinize his account books.”

Part of the agent’s responsibility included the distribution of annuities and supplies required to honor the treaties which had been ratified by Congress. To supplement their incomes, many agents would set up a store off-reservation where they sold the goods which had been intended as annuities for the Indians.

Getting the goods to the reservation required shipping and shipping agents generally overstated the millage involved. Suppliers who provided beef generally provided poor, underweight cows and charged for good, healthy animals. Suppliers saw the reservations as good places to send spoiled or unsalable goods. Money was made by all, and the Indians received very little of what they had been promised by the government. Historians Robert Utley and Wilcomb Washburn, in their book Indian Wars, write:

“From factory to agency warehouse, corrupt alliances enriched government officials and suppliers and penalized the Indians in both quantity and quality of issue.”

In 1868, a Congressional commission condemned the corruption of the Indian Department and noted abundant cases in which “agents have pocketed the funds appropriated by the government and driven the Indians to starvation.” Peter Nabokov reports:

“President Lincoln, and Grant after him, were increasingly aware that scandals within the Indian Bureau were not only costing the government money, they were frustrating the crucial task of making reservations congenial incubators for Indian transformation.”

In 1869, Congress and the Grant administration set out to reform the administration of Indian policies and to establish new policies for Indian affairs.

Board of Indian Commissioners

The Board of Indian Commissioners was created by Congress and was to be made up of distinguished philanthropists who served without pay. The Board was to oversee the purchase and distribution of goods and supplies for the Indian Service (which would later become the Bureau of Indian Affairs). In an article in the Chronicles of Oklahoma, Francis Paul Prucha reports:

“The men who made up the first Board of Indian Commissioners were wealthy businessmen, most of who had served with the Christian Commission during the Civil War, and who were motivated, indeed driven, by a sincere Christian philanthropic zeal.”

None of the members of the Commission were Catholics. Historian Joseph Genetin-Pilawa, in an article in The Western Historical Quarterly, writes:

“These men developed a reform agenda that focused on confining Indians within increasingly smaller reservations and cultural assimilation by any means necessary.”

Most of the members of the Commission had no actual experience with Indian communities. The Board of Indian Commissioners was headed by William Welsh, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant. Welsh was a critic of the Indian Bureau and supported the proposal to move the Indian Bureau from the Department of the Interior back to the Department of War.

With regard to the makeup of the Commission, historian Joseph Genetin-Pilawa reports:

“Interestingly, almost all of the men maintained business interests in the dry goods, mineral extraction, and transportation industries. These industries stood to benefit from Indian confinement in the West, and this fact suggests that perhaps their personal interests influenced their Indian policy work and their support of coercive reservations.”

The Board reported:

“The history of the government connections with the Indians is a shameful record of broken treaties and unfulfilled promises.”

The Board of Commissioners recommended the abandonment of the treaty system and the abrogation of existing treaties. They also recommended treating “uncivilized” Indians as wards of the government with the duty of government to “protect them, to educate them in industry, the arts of civilization, and the principles of Christianity”.

With regard to education, the Commissioners recommended establishing schools to introduce English to every tribe. According to the recommendation:

“The teachers employed should be nominated by some religious body having a mission nearest to the location of the school. The establishment of Christian missions should be encouraged, and their schools fostered.”

In reinforcing policies to bring Christianity, primarily Protestant Christianity, to the Indians, the report stated:

“The religion of our blessed Savior is believed to be the most effective agent for the civilization of any people.”

Indian Reform

William Welsh, the chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners, published a book entitled Taopi and His Friends; or, the Indians’s Wrongs and Rights in which he laid out his ideas for Indian reform. He believed that treaties should not be made with Indian tribes and that the large reservations should be broken up. Historian Joseph Genetin-Pilawa writes:

“A cornerstone of Welsh’s reform agenda was faith in the process of Christianization; however, he believed that if Indians were to embrace Christian civilization, they had to be dispossessed and held coercively on reservations.”

If Indians would not go willingly to reservations, Welsh explained, they should be forced to go or be exterminated.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Prior to 1869, the men appointed to the office of Commissioner of Indian Affairs had little or no experience with American Indians. They were appointed because of political loyalties rather than any knowledge or experience which they might have. In an effort to end corruption and bring a new direction to the Office of Indian Affairs, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed a Seneca Indian, Ely Samuel Parker, as Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

Ely Parker was born on the Tonawanda Reservation in New York in 1828. His mother belonged to the Seneca Wolf Clan and, in the matrilineal Seneca, this meant that he was Wolf Clan. He studied in several Euro-American schools and academies. As a teenager, he served as an interpreter and spokesman for the Tonawanda Seneca Reservation in their legal dispute with the Ogden Land Company. In 1851, he was elected as one of the 50 sachems of the Iroquois Confederacy (the Seneca are one of the six Indian nations that make up the Iroquois Confederacy).

He attempted a career in law but found that, as an American Indian, he could not be admitted to the bar. In the nineteenth century, Indians could not become citizens of the United States. In his biographical sketch of Ely Parker in The Encyclopedia of North American Indians, William Armstrong writes:

“When he was refused admission to the New York bar because he was not a citizen, Parker turned to engineering, learning that profession by working on the New York canals.”

For his formal education in Civil Engineering, Parker attended the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He quickly became a recognized success, working on the Genesee Valley Canal and on the Erie Canal. In addition to building canals, he also built a customhouse in Galena, Illinois where he met Ulysses Grant, a store clerk and army veteran.

During the civil war, he received a commission as a Captain of engineers in the Union Army. He soon joined General Grant as a staff officer and quickly became Assistant Adjunct General, an administrative position. He served as Grant’s military secretary and a member of Grant’s inner circle. In 1865, he transcribed the terms of surrender offered to General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Courthouse. He was probably the most literate of Grant’s staff and had good handwriting.

In 1865, he served with a commission that negotiated with the Indian communities that had joined the Confederacy during the war. Historian Joseph Genetin-Pilawa writes:

“His work was particularly significant because it demonstrated to other policy makers the importance of including Native voices.”

Historian Joseph Genetin-Pilawa notes:

“Since the end of the [Civil] war, Parker had served Grant as his military adviser on Indian affairs and during that time, developed a policy agenda which, at its heart, held a notion that the federal government had a responsibility to compensate indigenous peoples for an economic and political system of domination that had dispossessed them of land, resources, opportunities, and political autonomy.”

Regarding Indian policy when he was Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William Armstrong writes:

“The theory was to gather Indians onto reservations, where they could be introduced to ‘agriculture, to manufactures, and civilization,’ and to use military force on all who resisted. Parker, himself a military man, full concurred with this approach.”

Ely Parker did not view Indian tribes as sovereign nations even though the Supreme Court viewed Indian tribes as being sovereign nations. In his annual report, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs stated:

“The Indian tribes of the United States are not sovereign nations, capable of making treaties, as none of them have an organized government of such inherent strength as would secure a faithful obedience of its people in the observance of compacts of this character.”

Ely Parker also wrote:

“…great injury has been done to the government in deluding this people into the belief of their being independent sovereignties, while they were at the same time recognized only as its dependents and wards.”

Historian Joseph Genetin-Pilawa reports:

“Given the right tools, incentives, and opportunities, Parker believed, Native people would assimilate into mainstream culture and society on their own terms, according to their own time frame.”

His experience in dealing with corporations, such as land companies, showed him that when corporations influence public policy, the Indian people face injustice, dishonesty, greed, and dispossession. In his book Who Was Who in Native American History: Indians and Non-Indians From Early Contacts Through 1900, Carl Waldman writes:

“He cleared out corrupt bureaucrats from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and hired agents recommended by religious groups, many of them Quakers.”

While Ely Parker was the first American Indian appointed as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Henry Waltman, in his biographical sketch of Parker in The Commissioners of Indian Affairs, 1824-1977, writes:

“Much of the time Parker’s administration was indistinguishable from that of a paternalistic, though stern, white official.”

Leave a Reply