At the beginning of the twentieth century, the policies of the federal government regarding American Indians were based on the philosophy that Indians, like other immigrants, should assimilate into the English-speaking, Christian, American farming culture and that this could be best accomplished by transferring all tribal resources—land, mineral, timber—from Indians to non-Indians. Since the establishment of the Siletz Reservation in Oregon in 1855, non-Indians had been lobbying for this Indian land. In 1892, the reservation had been divided into 80-acre parcels under the General Allotment Act. Many of the 551 individuals receiving allotments had to sell their land to satisfy debts and taxes.

When the original allotment holders died, then the Indian Service would divide the land among the heirs. To simplify this process, Congress passed the Dead Indian Act of 1902 which allowed the Indian Service to sell off the land instead of dividing it. By 1905, 256 of the original allottees on the Siletz Reservation had died. This was about half of the original allottees.

In 1908, a bill was introduced in Congress which would allow the sale of the last five sections of Siletz tribal land in Oregon at the discretion of the Secretary of the Interior. The bill was supported by the acting Secretary of the Interior who claimed that it would lead to the Indians assimilating into American society and thus government supervision could be terminated. In 1910, the bill was finally approved, and less than one section of land was actually sold.

In 1908, the Indian Service closed the boarding school on the Siletz Reservation.

In 1906, Congress passed the Burke Act which abbreviated the trust period for allocated lands and allowed “competent” Indians to sell their lands. This sped up the transfer of reservation lands into Euro-American ownership. In his book The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980, E. A. Schwartz reports that the two significant changes in the Burke Act were:

“…citizenship was to be granted to allotment holders only when their properties were no longer held in trust by the government, and, more significantly, the fixed trust period was tossed out and the secretary of the interior was authorized to give ordinary titles to allotment holders when they were deemed competent.”

By 1910, the Indian agent for the Siletz Reservation estimated that 95% of the allotments had been sold.

With regard to Indian agriculture on the reservation, the Indian agent in 1910 reported:

“We visit Indians at their homes sometimes and talk with them about farming, not trying to tell them too much.”

The Indian agent felt that the Indian should be “thrown on their own resources.”

In 1911, there were 28,000 acres of agricultural land which had been allotted to the Indians. However, there were only 420 acres which were actually being cultivated.

In 1917, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells, sped up the assimilation of Indians and the termination of governmental support with a policy that lifted restrictions on Indians with a blood quantum of less than 50% and on educated Indians. Sells justified his racist policy saying:

“it is almost an axiom that an Indian who has a larger proportion of white blood than Indian partakes more of the characteristics of the former than of the latter.”

According to historian Francis Paul Prucha, in his book American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly:

“Sells’s program was disastrous for many Indians, who quickly lost or disposed of their individual lands as soon as they were declared competent and received patents in fee, but Sells seems not to have noticed.”

Historian Tanis Thorne, in his book The World’s Richest Indian: The Scandal Over Jackson Barnett’s Oil Fortune, reports two problems with the new program:

“First, releasing Indians from restricted status resulted in wholesale land loss and Indian impoverishment. Second, the Indian office’s primary indicator of competency in business affairs—blood quantum—was not reliable.”

In response to the new guidelines, three Indian Service officials were appointed to issue patents on the Siletz Reservation. It was anticipated by the non-Indians on the coast that many of the Indians would sell their lands as soon as they got their patents, and this would make as much as 18,000 acres of land available for sale. Agriculture boomed during World War I and then slipped into a depression by 1920, resulting in bankruptcy for many farmers, both Indian and non-Indian.

When the United States entered into World War I, Indian men were not liable to be drafted as they were not citizens. On the Siletz Reservation, 17 tribal members enlisted and 2 were killed in action.

In 1918, the day school on the Siletz Reservation was closed. The school had been under the direction of Robert DePoe, a tribal member and the son of Charles Depoe. Siletz children would now attend public schools.

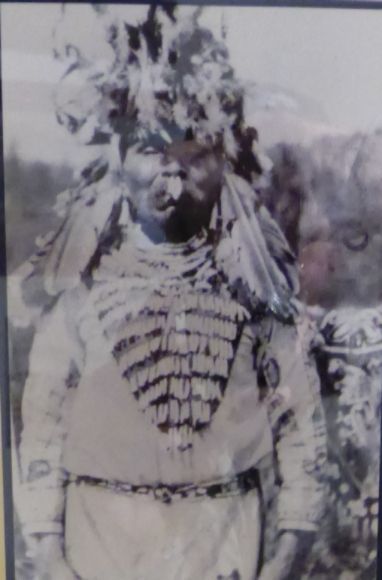

Shown above is Depot Charlie, also known as Charlie DePoe. This photograph is on display in the Burrows House Museum in Newport, Oregon.

Shown above is Depot Charlie, also known as Charlie DePoe. This photograph is on display in the Burrows House Museum in Newport, Oregon.

In 1925, the Siletz Agency was closed. E.A. Schwartz writes:

“The closing of the agency did not mark any great change in the way the Siletz people lived. For almost as long as the reservation existed, they had been adapting themselves to white society by going out to work for white people. This adaptation was not a deliberate result of any federal Indian policy either ideally or in application. It was a result of the failure of the government to make the reservation work as policy implied it should.”

Leave a Reply