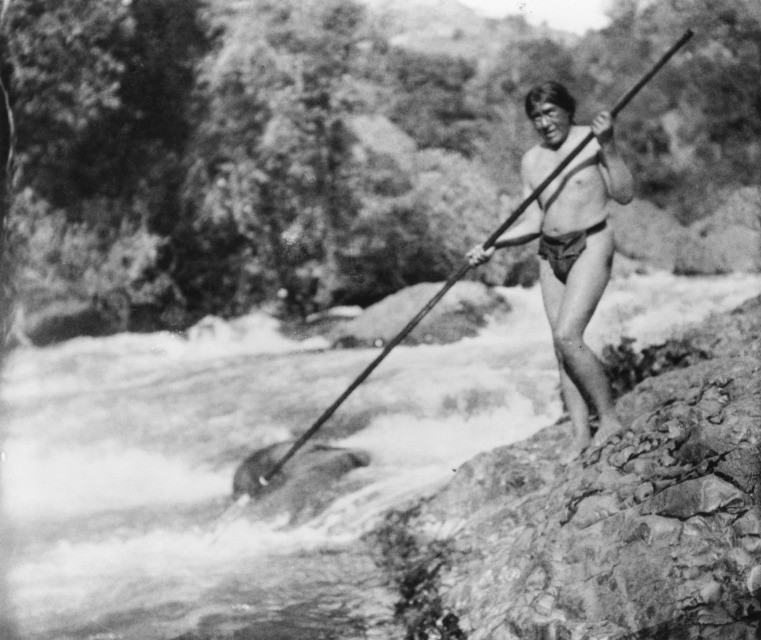

Ishi looks for some fish to spear, c. 1912 On March 25, 1916, a Yahi Indian of the Yana people named Ishi died of tuberculosis in his quarters at the University of California’s anthropology museum in San Francisco. He was about 55 years old.

Ishi looks for some fish to spear, c. 1912 On March 25, 1916, a Yahi Indian of the Yana people named Ishi died of tuberculosis in his quarters at the University of California’s anthropology museum in San Francisco. He was about 55 years old.  Ishi fixing his two-pronged fishing spear.

Ishi fixing his two-pronged fishing spear.

Thanks to national fascination with him almost from the moment he stepped out of the woods near Oroville, he is possibly the most famous California Indian who ever lived. Except for the final five years of his life, he lived completely outside the white world. During those five years, he was intensively studied. He became friends and a hunting companion of some of those who studied him, taught them the intricacies of his dialect and aspects of his culture, including how to knapp stone arrowheads the way he had been taught. In the latter case, his techniques are still used by many modern flint-knappers.

He was born about 1862, a time of vigilante attacks and other pressure on the Indians of northern California. The influx of non-Indians that began with the gold rush of 1849 was over, but the flood of immigrants to the state never stopped. Mining and other activities wreaked ecological havoc everywhere they turned, killing off food sources for the Indians and driving down their population by squeezing their habitat and by one of America’s least known happenings—the California genocide. Ishi was a survivor of that 25-year-long slaughter.

The first governor of California, Peter H. Burnett, didn’t start that genocide, but he added to it. In January 1851, he said: “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races, until the Indian race becomes extinct, must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.”

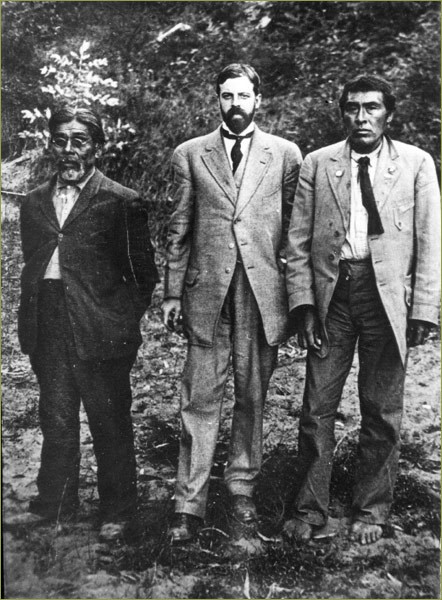

Yahi translator Sam Batwai, Alfred L. Kroeber, and Ishi in 1911.

Yahi translator Sam Batwai, Alfred L. Kroeber, and Ishi in 1911.

That “painful regret” didn’t stop future governors from supporting volunteer militias to hunt and kill Indians. Between 1851 and 1859, the state spent more than $1.3 million for this purpose. The federal government reimbursed California for some of this spending. The state offered scalp bounties of 25 cents each in 1856, raised to $5 in 1860. Some towns also offered their own bounties.

Groups like the Humboldt Home Guard, the Eel River Minutemen, and the Placer Blades terrorized and murdered local Indians. The 19th century historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote: “The California valley cannot grace her annals with a single Indian war bordering on respectability. It can, however, boast a hundred or two of them as brutal butchering on the part of our honest miners and brave pioneers, as any area of equal extent in our republic.”

At statehood in 1850, the Indian population of California was estimated to be 150,000, about half what it is thought to have been when the Spanish arrived. Thanks to the government-funded extermination policy, by 1900 only 16,000 remained.

Among them were Ishi, his mother and his sister, survivors of the Three Knolls Massacre of 1865. That is when an impromptu militia of white settlers had killed some 40 Yahi on Mill Creek, a tributary of the Sacramento River near Mt. Lassen in today’s Tehama County. The survivors, including 3-year-old Ishi, had fled.

Half of them were killed in 1867 or ’68 by another ad hoc militia. Its leader, Norman Kingsley, later said that during the slaughter, he had exchanged his .56 caliber Spencer rifle for a .38 Smith & Wesson revolver because the rifle “tore them up so bad,” particularly the babies. The few remaining Yahi fled into the wilderness where they effectively hid out for the next 40 years. In 1908, a survey team ran across Ishi’s camp. He fled with his sister and another man, but his mother was too frail to run. The surveyors looted the camp, taking everything of value. Soon afterward, the rest of Ishi’s tiny band died. For the next three years, he lived alone. But in 1911, starving, he stole into a slaughterhouse where he was caught by the butchers and briefly jailed.

Ishi’s quiver and arrows

Ishi’s quiver and arrows

It was at that point that he came to the attention of anthropologists Thomas Talbot Waterman and Alfred Kroeber, who would make the Indian their research assistant and life’s work. When the ambitious Kroeber first heard about Ishi’s appearance, he wrote to linguist Edward Sapir: “Have totally wild Indian at the museum. Do you want to come and work him up?”

Ishi spent a good deal of time teaching the linguists and anthropologists what he knew. But he was also quite involved in the community. He dated, he played with local children.

One of the most difficult adjustments for him was crowds. Before he went looking for a meal in that slaughterhouse, he had never seen more than perhaps 50 people all in one place.

After five years living in the white world that he had previously avoided all his life, he died of tuberculosis. In his culture, keeping the body intact for burial was important, but the doctors performed an autopsy, removed his brain and cremated the ashes. Those were buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in San Francisco, but the brain wasn’t interred with them for another 89 years.

Much has been written about Ishi, the most famous being the book published on the 50th anniversary of his emergence from the wild, Ishi in Two Worlds, written by Alfred Kroeber’s anthropologist wife Theodora. In 2003, anthropologists Clifton and Karl Kroeber, sons of Theodora and Alfred, edited Ishi in Three Centuries, a scholarly book on the subject that included essays by American Indians.

In 2004, anthropologist Orin Starn wrote Ishi’s Brain: In Search of America’s Last “Wild” Indian There was a television film in 1978, a mediocre biopic called Ishi: The Last of His Kind. In 1996, based mostly on the style of arrowheads that Ishi knapped, research archaeologist Steven Shackley concluded that Ishi likely wasn’t the last pure Yahi, but a mixed blood whose parents, like other California Indians may have been forced by white encroachment and slaughter into tribal mergers with their enemies. Proof of that theory likely will never be known. Today, there are no known members of the Yana, the larger group of whom the Yahi were a part.

Leave a Reply