Even the most casual tourist who travels through the Navajo lands of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah cannot help but notice the abundance of fine weavings commonly called “rugs” which are offered for sale at roadside stands, tourist traps, restaurants, museums, and fine arts galleries. Navajo weavings are some of the best-known and most easily recognized American Indian art forms.

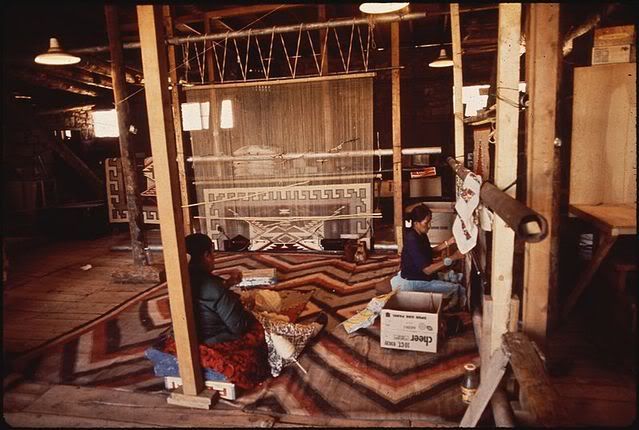

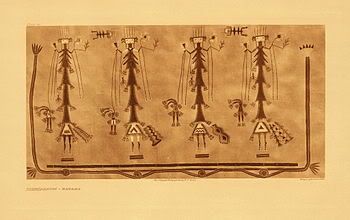

According to the oral tradition, at some point in the mythological past, Spider Woman taught Navajo men how to make an upright loom and then instructed Navajo women on how to use this loom to weave beauty. Beauty is an important part of Navajo culture-it is not a matter of being surrounded by beauty, but being involved in the process of beauty.

Navajo weaving is not just a way of making cloth or textiles: it is a form of artistic expression. While oral tradition gives Spider Woman credit for teaching weaving to the Navajo, the archaeology suggests an additional dimension to the story. Sometime in the 16th century the Navajo learned weaving from the Pueblo people in the Southwest and for more than a century, Navajo weavings closely resembled those of the Pueblos. Both the Navajo and the Pueblos at this time wove the same kinds of clothing.

There are some major differences between Navajo weaving and Pueblo weaving: in Pueblo culture, the men do the weaving, while in Navajo culture weaving is generally women’s work.

Among the Navajo, it is the process of weaving, not necessarily the final product, which is important. Weaving provides an opportunity to make individual decisions, to discipline one’s thought process, to practice self-control, patience, and tenacity, and to develop one’s skill. The process of weaving is closely attuned to spiritual concepts. Working at her loom, the weaver seeks to create a single whole that blends fine and bold contrasts in color, feature, and design. In this way, the weaver seeks to emulate the process by which the Holy People created the world.

When a Navajo weaver sits down before her loom to start a new weaving, she has a design in her mind-it is not written down and it is not a design which she has done before. Navajo weavings are always designed anew and the designs are always changing, moving, and flowing. The Navajo weavers see the process of weaving and their designs as a form of communication. In this way, the process of Navajo weaving is like a language with codes and conventions that carry meanings embedded in specific historical, cultural and familial contexts.

Weaving with cotton was common in the southwest prior to the arrival of the Spanish. After the arrival of the Spanish, the Navajo acquired churro sheep and began weaving with wool. Within a relatively short period of time they became proficient in weaving wool and by the early 18th century they were already selling their textiles to both Spanish and Pueblo communities.

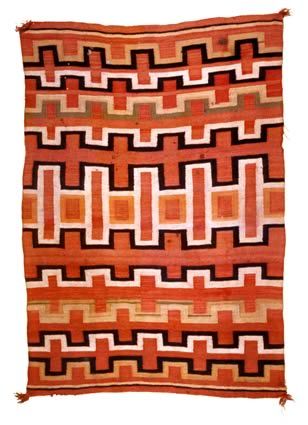

During the 19th century, Navajo wearing blankets were traded throughout the Southwest and into adjacent culture areas. These blankets are woven wider than long and are worn by both men and women, draped around the shoulders. Outside of the Southwest, these blankets became prestige items and are often referred to as “chiefs’ blankets”. These blankets were so tightly woven that they would shed water. The use of indigo dyes and costly yarns meant that they commanded a high price. On the Great Plains, only those people with significant resources could afford such a blanket, thus the designation of Chief blankets.

The Chief blanket is based on a simple striped weaving pattern. The blankets had dark horizontal stripes which were organized into a solid broad band at the blanket’s center. At the top and bottom there were bands which were half as wide as the center band. Between the center and the border bands there would be narrower alternating black and white stripes.

The earliest known Chief blanket, dating to about 1775, consists of evenly spaced alternating brown and white stripes. There are four rows of narrow stripes at each end. By the early part of the 19th century, Navajo weavers broadened the stripes giving them an additional sense of depth. Outlining the horizontal dark brown stripes with deeply saturated indigo blue added even more depth to the design.

By 1850 many Navajo weavers had adopted a technique known as tapestry weave and added geometric forms to the Chief blanket. The horizontal plane is interrupted with twelve vibrant red rectangular bars. When the blanket is draped about the body, the vertical elements are visible down the back and front of the wearer.

About 1860, Navajo weavers began adding terraced triangles and diamonds to the design of the Chief blanket.

By the end of the 19th century, Navajo weavers were using a two-faced weave. This means that one pattern could be developed on the front, and a different pattern, usually one featuring simple stripes, could be done on the reverse side.

In addition to blankets, Navajo weavers also produced a number of other woven items, including sash belts, garters, saddle cinches, women’s dresses, knitted socks, and leggings.

While in today’s market, Navajo rugs are most frequently woven and traded, this is an aspect of Navajo weaving that emerged toward the end of the nineteenth century in response to a globalized market for American Indian goods. This will be discussed in a separate essay.

Leave a Reply