In 1792, American ships from Boston under the command of Captain Robert Gray sailed along the Pacific Coast of what is now Oregon and Washington seeking to trade with the coastal Indians and obtain furs which were valuable in the European and Chinese markets. On May 7, Gray sailed into a large estuarine bay about 45 miles (72 kilometers) north of the mouth of the Columbia River. Ignoring any possibility that the indigenous people who lived in the area might have had a name for it, he named it Bullfinch Harbor in honor of Charles Bullfinch of Boston, one of the owners of the Columbia Rediviva. Later, Captain George Vancouver named it Grays Harbor in honor of Captain Robert Gray and this is the name that it carries today.

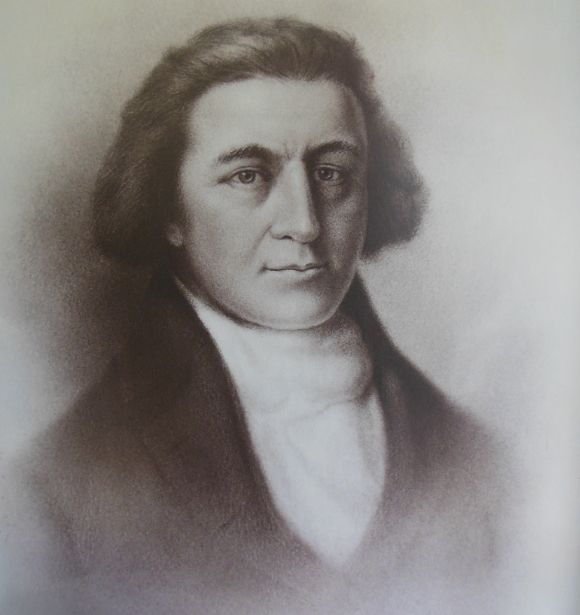

Shown above is a portrait of Robert Gray which is on display in the Polson Museum in Hoquiam, Washington.

While most history books credit John Gray with “discovering” the harbor that currently carries his name, the people who lived there when he sailed in didn’t feel like the area needed to be “discovered.” When the ship sailed into the harbor, the Chehalis came out in canoes to greet it. John Boit, the ship’s fifth officer reported:

“Vast many canoes came off, full of Indians. They appeared to be a savage set, and was well arm’d, every man having his Quiver and Bow slung over his shoulder.”

The Americans traded with the Chehalis for some fish and furs. Boit also noted:

“The men were entirely naked, and the women, except a small apron made of rushes, was also in a state of nature. They were stout made, and very ugly.”

When the natives approached again the following day, the ship opened fire on the canoes with their cannons, destroying one canoe with 20 men in it and driving the others off. Boit wrote:

“I am sorry we was obliged to kill the poor Devils, but it could not with safety be avoided.”

The message to the people was clear: the intruders were not particularly peaceful.

The Chehalis are a group of culturally, linguistically, and historically related tribes that have lived in the Pacific Northwest for thousands of years. With regard to language, Chehalis is classified as a part of the larger Salish language family. The Salish language family is found on the Northwest Coast and in the Columbia Plateau area. Salish is generally felt to have great antiquity in the Northwest Coast. Linguists estimate that this language family may be 6,000 years old, although some feel it may be as young as 3,000 years old.

The Chehalis are generally divided into two broad groups: Upper Chehalis and Lower Chehalis with the boundary between the groups the confluence of the Chehalis River and the Satsop River. The lower Chehalis include the Copalis, Wynoochee, and Humptulips. The Satsop are part of the Upper Chehalis.

Like the other Indian nations living along the Pacific coast of what is now Washington and British Columbia, the Chehalis subsistence activities emphasized fishing and marine mammal hunting. Sturgeon was a popular item and often weighed 200 to 300 pounds. Sturgeon fishing was an art and was done with a large hook fasted to a cedar and spruce bark rope. This was fitted to a long pole, often 20 feet or longer. Holding the rope and pole, the channel floor would be probed for the large fish. It would sometimes take hours to land a large sturgeon. It is reported that a skilled fisherman would pull a 300-pound sturgeon into a canoe without shipping water.

In addition, they gathered shellfish and plants. Mussels and cockle clams were staples.

While the stereotype of American Indians envisions them as living in tipis, the Indians of the Northwest Coast lived in substantial wooden houses. These multi-family houses were built with planks on a post and beam frame. Coast Salish houses were typically 30 to 50 feet wide and they ranged from 50 to 200 feet in length.

In 1824, Hudson’s Bay trader John Work brought a large trading party into Grays Harbor. He reported:

“We passed 4 villages of the Chihalis nation, 2 houses in the first, five in the second, 2 in the third and 3 in the fourth, opposite which we encamped.”

Work described the houses:

“These peoples houses are constructed of planks set on end and neatly fastened at the top, those in the ends lengthening towards the middle to form the proper pitch, the roofs are cased with plank, the seams between which are filled with moss, a space is left open all along the ridge which answers the double purpose of letting out smoke and admitting the light.”

Salish houses were divided into compartments. The compartment would occupy the space between two rafters and would contain a hearth. Each compartment would be occupied by two related nuclear families. The walls were usually lined with rush mats which helped to seal the cracks between the wall planks. These mats could also be used as sleeping mats and as pillows. Along the walls there was often a bench which was used for storage and sleeping. Items would be stored both on top of the bench and underneath it.

The houses would usually be arranged in a single row facing the water. Villages might have as few as four or five houses, while many villages would have 15 or more.

One of the cultural features of the Northwest Coast Indian nations is the potlatch. The potlatch is a series of songs, dances, and rituals. As a part of the potlatch, the host clan gives away a great deal of wealth which serves as a validation of the clan’s status of the society. Wealth was important to the Indian nations of the Northwest Coast and giving it away was a way of gaining status.

Potlatches are held to honor the dead as well as to celebrate life transitions such as marriages and births. The potlatch brings people-both living and dead-together. The guests at a potlatch see and experience the social business of the event, such as the inheritance of a name. They mentally record and validate that which has happened.

The potlatch itself often lasts for days with special songs for greeting the arriving guests and large quantities of food. During the several days of the potlatch, the hosts provide the guests with two large meals per day.

Since Americans are obsessed with the acquisition of property, the idea of giving it away is somehow offensive. Christian missionaries opposed the potlatch and it was banned in both Canada and the United States. However, Indian people continued the potlatch away from the government and the missionaries. The potlatch is currently legal in both countries

One of the functions of the potlatch is to memorialize those who have died. Among most of the Northwest Coast Indian nations, death involves reincarnation.

At the time of first contact with Europeans, the Coast Salish used wooden coffins and canoes set up in graveyards as a means of disposing of dead bodies. Regarding Chehalis burials, nineteenth century school superintendent Edwin Chalcraft reported:

“It was the old-time Indian custom in burying the dead at Chehalis to have the grave shallow enough to permit the cover of the box in which the body had been placed to be level with the surface of the ground, and then build a small house, about three feet high, over the grave.”

Leave a Reply