For more than a thousand years, American Indian agriculturalists have been living in villages in what is now Arizona and New Mexico. When the Spanish first encountered these villages, many of which had multi-story apartment complexes built from stone, they referred to them as “pueblos,” the Spanish word for village.

Europeans have grouped these diverse people together under the designation Pueblo Indians based on a few common traits: they are agriculturalists who grow corn, beans, and squash; they built permanent villages with a central plaza; and most have kivas (underground ceremonial centers). They are not, however, a single people, tribe, nation, or group: the peoples grouped together as Pueblos speak six mutually unintelligible languages and occupy more than 30 villages in a rough crescent more than 400 miles in length.

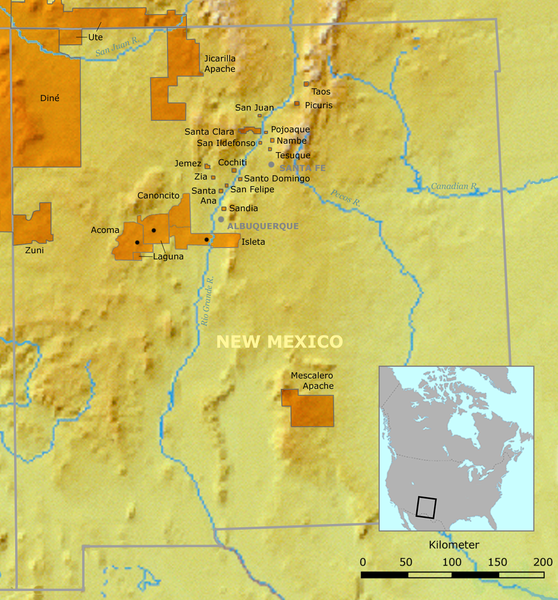

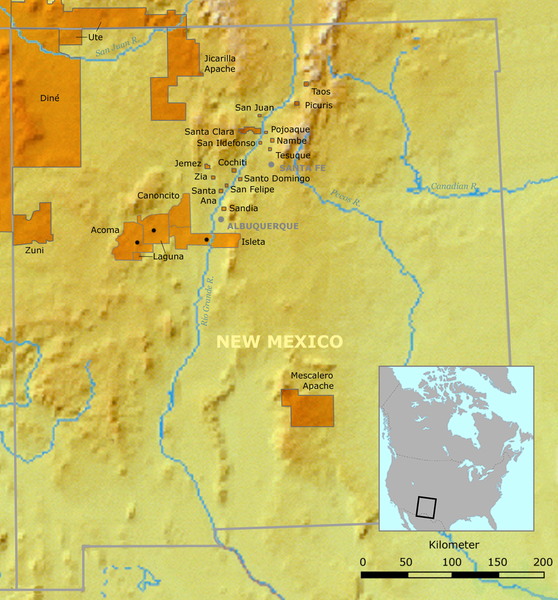

The map above shows the current Pueblos in New Mexico. Not shown are the Hopi Pueblos which are in Arizona.

The Pueblos are generally divided into two major groups: (1) eastern (Tanoan and Keresan speakers) with a permanent water source which enables them to practice irrigated agriculture, and (2) western (Hopi, Hopi-Tewa, Zuni, Acoma, Laguna) who rely on dry-land agricul¬ture.

Acoma Pueblo is shown above.

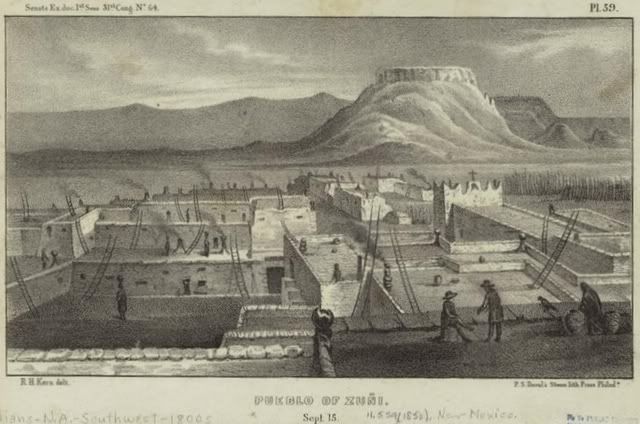

An 1850 sketch of Zuni is shown above.

The Pueblos have a long tradition of weaving. For many centuries prior to the European invasion of North America, Pueblo weavers were making cloth which was traded over long distances. Fabrics were woven from a variety of different plant materials-both domestic and wild-and it was not uncommon for human hair, dog hair, and wild animal hair to be incorporated into fabrics. The important plant materials used for weaving textiles included milkweed, hemp, mesquite, cliff rose, willow, yucca, agave, stool, and bear grass. In addition, both feathers and fur were also used in weaving. Bird feathers were used in making warm blankets.

One of the plant fibers used for weaving was, and sometimes still is, yucca which can be processed to produce a linen-like fabric. Among the Zuni, the central leaves of the yucca plant were gathered and each leaf was folded into a piece that was about 10 centimeters (3.5 inches) long. These pieces were then placed in a pot of boiling water together with some wood ash. The skin would then be removed from the leaves and chewed (generally by the children). After this, the fibers could be separated and straightened. After the fibers had dried-usually by hanging them in a storage room-they would be soaked in cold water and then rubbed between the hands to soften them. The softened fibers would then be pulled into a fluffy mass which would allow them to be spun and woven like cotton.

Pueblo weavers used two basic types of looms. The back strap loom was used to make sashes and belts. The vertical loom was used for producing larger fabrics, including blanks, ponchos, and cloth for making dresses and shirts. The vertical loom can be anchored on a ceiling beam on the top and then on four floor anchors on the bottom.

The backstrap loom is attached to an interior wall and then tension is maintained by a backstrap which allows the weaver to change the tension in the loom by changing the position of the body. The cloth produced using the backstrap loom is narrower than that produced with the vertical loom.

Shown above is a sash.

The development of loom weaving in the Southwest coincided with the introduction of domesticated cotton. By 425 BCE, the Hohokam in Arizona were raising cotton and trading it widely. By 700 CE, the Ancestral Puebloan people (sometimes called Anasazi by archaeologists) were growing cotton in New Mexico. Upright looms appear shortly after this.

By 1260 CE, the Hopi village of Homol’ovi was the center of cotton trade between the Hopi and other tribes in the Southwest. Homol’ovi had 200 rooms and had an estimated population of about 200 people.

At Zuni Pueblo, men traditionally spun and wove cotton. The cotton they used, however, they did not grow themselves, but obtained from the Hopi.

Among the Hopi, weaving was a traditional male activity. Hopi cotton cloth was a highly valued trade item among Indian people in the region. Hopi textiles, including the coarse white cotton lengths used for kilts, sashes, and shawls, was traded throughout the Southwest and south into Mexico.

According to the Hopi oral tradition, it was Spider Woman who taught the Hopi how to weave cotton in the ancient time. The efforts of the weaver are therefore viewed as a manifestation of the creative power of spirituality. Weaving is not seen as an act in which one creates something by oneself; it is seen as an act in which one uncovers a pattern that was already there.

After sheep were introduced to the area by the Spanish, wool began to replace cotton in Pueblo textiles.

Leave a Reply