When the United States acquired what is now New Mexico and Arizona in 1846, a number of Pueblos were brought under American rule according to the Discovery Doctrine. The Pueblos created a few problems for the Americans, however, as they did not conform to the stereotype of nomadic Indians whose lives centered around hunting. There were, in fact, debates about whether or not the Pueblos should actually be considered as Indian tribes. It would take thirty years until the Supreme Court would issue a ruling on this question.

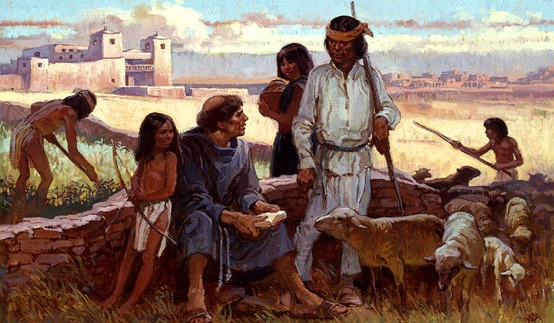

A second problem faced by the new American rulers was religion. As a Christian nation, United States policies regarding Indians required their conversion to Christianity, preferably Protestant Christianity. The Pueblos, when under Spanish rule, had nominally become Catholics. While American policies actively discouraged Indian pagan practices, the Americans at this time did not care much for Catholicism either. The American government, therefore, found itself supporting Protestant missionaries to the Catholic Pueblos. Under Spanish and Mexico rule, the Pueblos had adopted Catholicism and had combined this with their own religious practices without any loss of the basic fabric of their life. With the Americans, however, they were faced with proselytizing Christians who sought to destroy Pueblo culture.

In 1847, the New Mexico territorial legislature passed an act entitled “Indians” which recognized the Pueblos as political and corporate bodies. According to the act, the Pueblos were living in towns and villages on lands granted to them by the Spanish and Mexican governments. In effect, the territorial legislature enacted a fantasy which did not recognize the Pueblos as the original owners of the land, but claimed that their occupancy rested on grants of land by foreign governments.

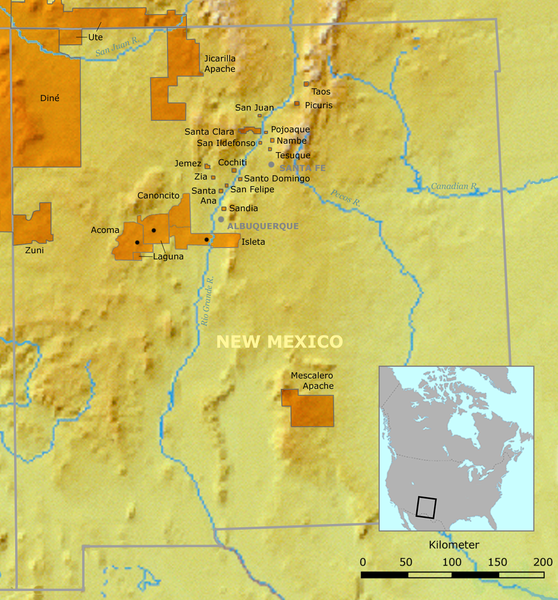

In 1850, James S. Calhoun, the first Indian agent in New Mexico, negotiated a treaty between the United States and the Pueblos of Santa Clara, Tesuque, Nambe, Santo Domingo, Jemez, San Felipe, Cochiti, San Ildefonso, Santa Ana, and Zia. The treaty stated that the boundaries of each Pueblo

“shall never be diminished, but may be enlarged whenever the Government of the United States shall deem it advisable.”

In addition, the treaty stated that the Pueblos shall be governed by their own laws and customs. The treaty was never ratified by the United States Senate. However, the treaty was understood by the Pueblos as the standard for governing their relations with the federal government.

In 1850, a delegation of Hopi from Arizona visited Agent James S. Calhoun to determine what the policies of the United States were toward them and to complain about Navajo raids. From the Hopi, Calhoun learned that the Hopi pueblos were autonomous. He reported:

“From what I could learn from the Cacique, I came to the conclusion, that each of the seven Pueblos, was an independent Republic, having confederated for mutual protection.”

In 1851, 12 New Mexico Pueblo tribes met with the American Indian agent and expressed their desire to maintain their traditional customs and usages. There is no indication of the response by the American government to this desire.

In 1852, five leading men from Tesuque-José María Vigil, Carlos Vigil, Juan Antonio Vigil, José Domingo Herrera, and José Abeyta-traveled by horseback, steamboat, and train to Washington, D.C. where they met with President Millard Fillmore. The purpose of the delegation was to argue for the rights promised in a Pueblo treaty signed in 1850. The delegation spent six weeks in Washington and was taken to all of the standard destinations, including the Smithsonian Institution. In their meeting with the President, Fillmore indicated that he personally would look into the matter of their treaty.

In 1852, a delegation from Santa Ana Pueblo traveled to Santa Fe to meet with the American superintendent to raise the issue of infringements on their land. The superintendent, however, was not present and the Americans simply dismissed their complaints as “trifling” and “no business of any consequence.”

The New Mexico territorial legislature passed a law in 1853 prohibiting the sale of liquor to Indians and declared that “Indian” did not include the Pueblo Indians.

In 1855, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs asked Congress to repeal the law which defined the Pueblos in New Mexico as corporate entities which could sue and be sued in local courts. He explained that the Pueblos had suffered greatly from this law because most suits were filed by non-Indians with an interest in obtaining Pueblo land. However, Congress did not act on this recommendation.

An 1858 Congressional act confirmed the Spanish land grants to several New Mexico Pueblos: Acoma, Jemez, Chochiti, Picuris, San Felipe, San Juan, Santo Domingo, Zia, Isleta, Nambe, Pojuaque, Sandia, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Taos, and Tesuque. The Spanish land grants to Indians had been superimposed upon Indian aboriginal rights dating from time immemorial. It would now seem that the Pueblo Indians should be claiming rights both under the land claims and under their original rights as first owners of the land.

In 1864, the Pueblo governors were given “Lincoln canes” as symbols of their office and authority. Engraved on the silver head of each cane is the name of the Pueblo, the year, and “A. Lincoln.” The canes originally cost $5.50 each.

The United States issued land patents in 1864 for Nambe, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Picuris, Zia, Sandia, San Felipe, San Ildefonso, Pojuaque, San Juan, Santa Clara, Taos, Tesuque, and Santo Domingo Pueblos in New Mexico.

In 1867, the territorial chief justice in United States v Ortiz ruled that the Pueblos were not Indians under the definition of the Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834. The Pueblos protested the decision. The Indian agent for the Pueblos, noting that the federal government had filed an appeal in the Supreme Court, asked the government to protect the Pueblos.

The United States officially established an Indian Agency for the Hopi in 1869. However, the agency was located in Fort Wingate rather than near the Hopi pueblos in Arizona. In addition, the agency was officially named the “Moqui Pueblo Agency,” a name which the Hopi felt was insulting. Two years later, the agency was moved from Fort Wingate to Fort Defiance. In 1873, the agency was moved from Fort Defiance to Keams Canyon which is about 13 miles away from the Hopi pueblo of Walpi.

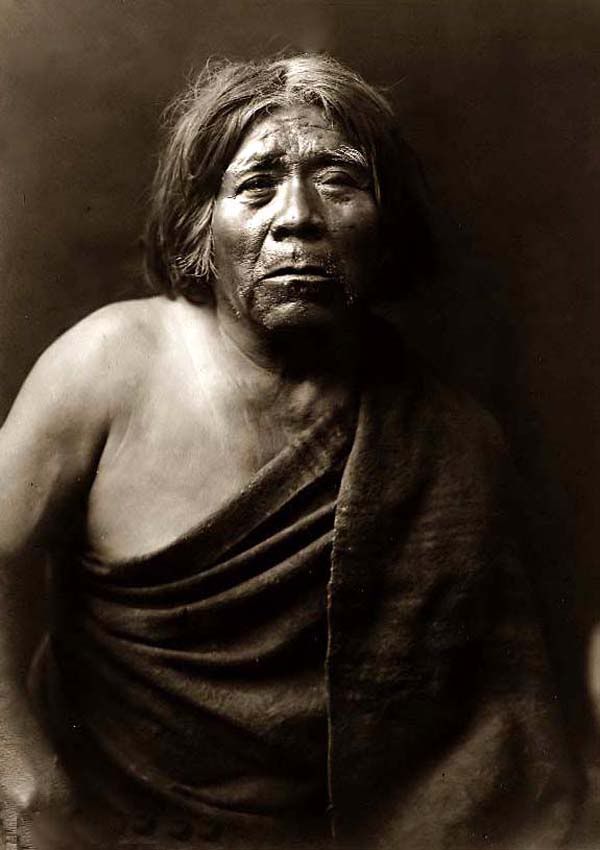

In 1869, in the case of United States versus Lucero, Chief Justice Watts characterized Indians as “wild, wandering savages”, but noted that this description did not hold for the Pueblos who, he claimed, have been cultivating the soil for three centuries. The judge’s comments seem to imply that the Pueblos learned agriculture from the Spanish and appear to reflect ignorance regarding many centuries of Indian agriculture prior to the Spanish arrival in the Americas.

In 1869, a special inspector for the Indian Office recommended that the Pueblos be declared citizens and required to pay taxes on their crops, herds, and orchards.

Congress in 1869 passed legislation which formally recognized the Santa Ana Pueblo land grant in New Mexico.

In 1871, the Indian agent for the Pueblos reported that holdings by non-Indian squatters on Pueblo lands were of such great value that the United States government could not afford to compensate them if they were forced to move. Instead, he recommended that the Pueblos sell their lands to these squatters.

Congress authorized the extension of federal services to New Mexico’s Pueblo Indians in 1872.

In 1873 the Bureau of Indian Affairs considered relocating the Hopi from their Arizona pueblos to land along the Little Colorado River or to Oklahoma. The Hopi vowed to resist any relocation as their ancient contract with the Great Spirit Massauw makes removal from the land impossible. After discussions with the Hopi, the Indian Agent recommended that a separate Hopi reservation be established.

The United States Supreme Court, in the 1876 United States versus Joseph, declared that the Intercourse Act of 1834 was not applicable to the Pueblos of New Mexico. The Court viewed the Pueblos as having a settled, domestic existence and therefore were not subject to laws which were passed for the protection and civilization of “wild Indians.” Furthermore, the Court asserted that Pueblo land titles were given to them by the Spanish government. As a result, 3,000 non-Indians settle on Pueblo lands.

The Supreme Court ruling denied the Pueblos the protection of the federal government and placed them within the jurisdiction of the local courts and officials. The Court did not define the Pueblos as citizens, and thus they did not have the right to vote, nor did they have the right to hold public office. While the Court excluded the Pueblos from participation in political life, it opened up the way for their lands to be appropriated for private enterprise by non-Indians.

Leave a Reply