In 1851, the U.S. Army sent out an exploratory party into northern Arizona. The Yavapai response to this party was to flee and stay out of sight. In one instance, the American scouts surprised a Yavapai party gathering piñon nuts. The Indians immediately fled and then watched from a distant hill as the invaders plundered their camp. When the Americans encountered a second abandoned camp, they left a tobacco offering instead of looting it.

Two years later, an American group which was invading Yavapai territory was ambushed. While the Yavapai attackers had the advantage of numbers, their clubs and arrows were no match for the defenders’ Colt revolvers. The Americans reported that they killed 25 Yavapai.

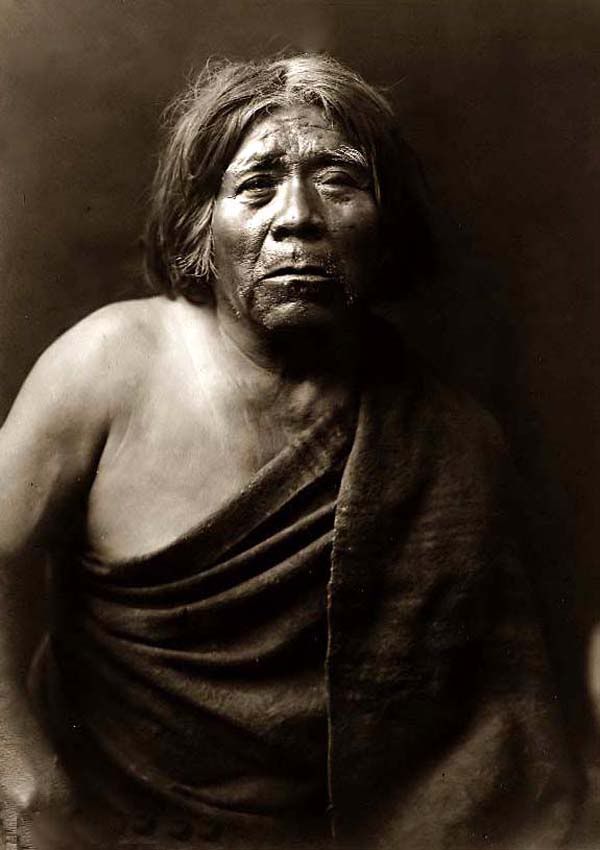

In 1863, representatives from the United States met with the leaders of a number of tribes at Fort Yuma in order to negotiate a treaty of peace. Among those attending was Quashackama, a prominent Yavapai leader.

The purpose of the treaty was to promote safe travel in tribal territories by the Americans. The tribes also promised to help the Americans in their war against the “Apache Tribes.” The treaty was not ratified by the Senate.

About the time when the treaty was being negotiated, gold was discovered at Lynx Creek in Yavapai territory. As with gold discoveries in other parts of Indian country, this brought an influx of miners who had little concern for either Indian rights or Indian lives. The miners disrupted the traditional Yavapai subsistence cycle and began a genocidal war against the tribe.

A group of 38 gold miners using the guide services of Mohave leader Iretaba followed the Hassayampa River into Yavapai territory. A party of 30-40 Tolkepaya Yavapai men stopped the miners. The miners told them that they had come in peace, that their only interest was in finding gold, but they would hunt humans if they met with any resistance. The Yavapai told the miners that if they turned back they would not be molested. Iretaba attempted to persuade the Americans to go west to the Colorado River. The miners, however, were not persuaded and were convinced that there was gold farther north on the Hassayampa. The Yavapai, unwilling to test the miners’ firepower, left. The Mohave guides took the miners’ entire supply of tobacco and then slipped away at night to head home. The miners continued into Yavapai territory, found gold, and staked out mining claims.

American teamsters murdered a Yavapai man they claimed to have caught stealing from their wagon train. Prospectors killed two Yavapai near the Weaver mines. A mining party lost four burros and in retaliation the miners killed about 20 Yavapai. The miners later found that their animals had simply wandered away from camp. In order to deal with the increasing violence-meaning, to reduce the possibility of American deaths-the U.S. Army established Fort Whipple in Yavapai territory.

In 1864, Yavapai headman Quashackama and other Yavapai leaders went to La Paz to meet with the American Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Representatives from the Quechan, Mohave, Chemehuevi, and some of the Pai bands are also present. The Superintendent proposed the establishment of a 75,000 acre reservation along the Colorado River. The Indian leaders agreed to confine themselves to this new reservation and to give up claims to all other lands. In exchange for this, the federal government agreed to provide an irrigation canal to ensure successful crops each year. However, no treaty was signed.

The violence between the Yavapai and the American miners continued in 1864. The Yavapai killed three miners along the Hassayampa River. The killings were in response to the murder of several Yavapai by miners in the past year. In response, soldiers from Fort Whipple attacked two Yavapai camps. Fourteen Yavapai were killed and seven wounded.

American aggression continued when an American rancher led an Indian-hunting expedition into Yavapai territory. The expedition encountered a large group of Yavapai and Tonto Apache who had gathered in four separate camps to gather agave and hunt in the Fish Creek area. When the Yavapai and the Tonto Apache saw the Americans, they held council among themselves. Some reported that there were some Maricopa warriors in the expedition who had called to them and assured them that the Americans had come in peace. Delshe, a Yavapai headman, cautioned that it might be foolish to assume that the Maricopa, their traditional enemies, had suddenly become their friends. After some discussion, a party of Yavapai and Tonto Apache approached the Americans in friendship. The Americans invited them into their camp, seated them, and offered them presents of tobacco, clothing, and piñole. The Americans then opened fire, killing 24 of their guests, including 3 young women.

Following this event, the American Indian-hunting expedition attacked a number of Yavapai camps, killing 30 Yavapai in one attack. Indian-hunting was supported materially and financially by the U.S. Army, the Arizona territorial government, and private contributions. It represented the vanguard of American settlement in central Arizona.

In related events, the territorial governor led an Indian-hunting expedition from Fort Whipple into the Verde Valley where they destroyed a Yavapai camp and killed five Yavapai. In other instance, the California and New Mexico Volunteers raided Yavapai camps and killed at least 30 Yavapai.

In 1865, soldiers from Fort Whipple attacked a Yavapai camp and killed 28 men, women, and children. Among those killed was Hoseckrua, a noted headman.

After 1865, American policies regarding the Yavapai were split between forcing them onto a reservation in some area which could not be used by American farmers and miners, and/or extermination through military action.

Leave a Reply