The Choctaw Removal

By 1830, non-Indians in Mississippi, motivated by greed and racism, were strongly advocating the removal of the Choctaw from the state. According to the citizens of Mississippi (Indians could not be citizens at this time), the reasons for the Choctaw removal included:

(1) Mississippi needed more land to attract immigrants from the east

(2) The Choctaw imposed a heavy financial burden on the state because they did not pay taxes

(3) The Choctaw harbored runaway slaves and non-Indian criminals

(4) They were hunters, not farmers, and hence not devoted to cultivating their fields

(5) They were inferior human beings, incapable of being civilized and therefore Mississippi must remove them as one removes a cancer

(6) Their lands were all within state boundaries and therefore the land belonged to Mississippi

Choctaw Background:

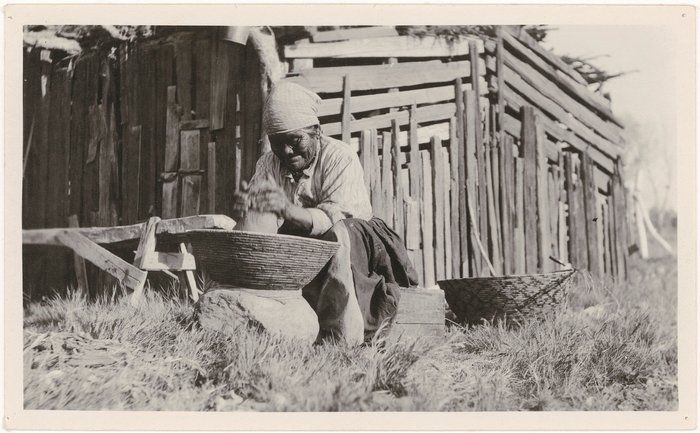

In general, the Indian nations that occupied what is now the American South were skilled farmers. For more than a thousand years, they had been raising corn, beans, squash, and other plants and their surplus agricultural products had allowed the unskilled non-Indians to survive when they first invaded.

Among the Choctaw, it is estimated that corn provided about two-thirds of their diet. In addition to corn and beans, the Choctaw also grew squash, sunflowers, sweet potatoes, and tobacco.

Unlike the Europeans, the Indians of the Southeastern Woodlands did not view land as private property. Land was held in common with individuals and families having use rights. These farming rights were held as long as they continued to use the land. Use rights were generally respected and an individual or family would not seek access to a piece of land until it had been abandoned.

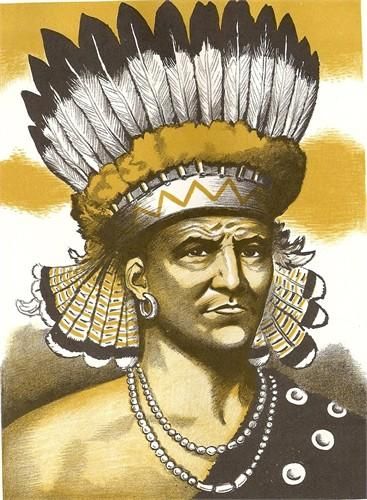

The Choctaw, at the time of European contact, were a loosely organized confederacy composed of three distinctly different divisions: Okla Falaya (Long People), Okla Tannap (People of the Opposite Side), and Okla Hannalia (Sixtown People). The people were living in more than 100 autonomous villages. Chiefs were selected from the senior matrilineal clan in the district. While there was a mingo (leader) for each district, there was no single overall mingo.

The Americans:

Beginning with the creation of the United States, its citizens and political leaders had discussed the idea that no Indians should be allowed in the new country. At the beginning of the nineteenth century this idea took root in the idea of removal. First promoted by Thomas Jefferson, the idea was simple: Indians should be removed west of the Mississippi River so that their lands could be developed. In order to promote this idea, it was necessary to ignore the fact that Indians had been farmers who had developed their lands for thousands of years and promote the idea of Indians as wandering hunters. With the purchase of the right to govern the Louisiana Territory in 1803, the U.S. had a place for Indian removal.

In 1803, President Jefferson told a Choctaw delegation:

“It is hereby announced and declared, by the authority of the United States, that all lands belonging to you, lying within the territory of the United States shall be and remain the property of your Nation forever, unless you shall voluntarily relinquish or dispose of the same.”

In that same year, Jefferson sent agents to the Choctaw to obtain lands from them. When the Choctaw leaders refused to discuss the matter of land cession, the United States officials then presented them with the overdue bills from Panton, Leslie and Company (a British trading company) and demanded immediate payment. As a result, the Choctaw chiefs signed the Treaty of Hoe Buckintoopa which ceded 853,760 acres of land to the United States. Two years later, the Americans used the same tactic to coerce the Choctaw leaders into signing another treaty in which they ceded four million acres of land in order to pay off debts to the trading company.

In 1817, Mississippi became a state and thus put more pressure on the Choctaw to give up their lands so that non-Indians could develop cotton plantations. In this same year, President James Monroe tells Congress:

“The hunter state can exist only in the vast uncultivated desert. It yields to the more dense and compact form and great force of civilized population; and of right it ought to yield, for the earth was given to mankind to support the greatest number of which it is capable, and no tribe of people have a right to withhold from the wants of others more than is necessary for their own support and comfort.”

In 1818, the United States sent a delegation to meet with the Choctaw leaders and present them with a proposal to move to the west. The Choctaw leaders refused to discuss the matter. The non-Indians in Mississippi were not pleased with the failure of the negotiations and brought pressure for a “get tough” policy regarding the Choctaw.

The following year, the Secretary of War sent a new delegation, one led by Andrew Jackson, to meet with the Choctaw to discuss removal. For three days, Jackson lectured the Choctaw, threatened them, and cajoled them. Choctaw leader Pushmataha bluntly replied:

“We wish to remain here…and do not wish to be transplanted into another soil.”

Pushmataha also pointed out that the land west of the Mississippi was very poor and that the government was trying to cheat them by asking them to give up good farm lands for poor farm lands.

In 1820, the Mississippi state legislature proposed that the United States purchase Choctaw lands for “a small consideration.” Newspapers reported that the governor, the legislature, and the people of Mississippi (meaning Euroamericans) were greatly annoyed with the Choctaw and felt that Choctaw land ownership was a great detriment to the state.

In the same year, Andrew Jackson once again led a delegation to discuss removal with the Choctaw. The council was held at Doak Stand and the Americans provided each Indian with a daily ration of 1.5 pounds of beef, a pint of corn, and free access to alcohol. While most of the Choctaw drew the rations, the followers of Puckshunubbee refused as they did not want to accept American hospitality under false pretenses. At the council, the Choctaw leaders were told that if they did not cede their land to the United States, the government would stop protecting the Choctaw from non-Indian settlers and from the territorial designs of the states and that state government would simply assume control over Choctaw affairs and take the land anyway.

Under intense pressure from the U.S. government, the Choctaw leaders signed the Treaty of Doak’s Stand giving 6 million acres of land in Mississippi to the United States. In exchange, the United States was to give the Choctaw a similar piece of land west of the Mississippi River and to support all Choctaw migrants to this land for one year. In what was left of the Choctaw territory east of the Mississippi River, the Choctaw are to be allowed to live undisturbed and to eventually become American citizens. Each man who migrated to the west was to be given a blanket, kettle, rifle, bullet molds, powder, and enough corn to last his family for a year.

While non-Indians in Mississippi were pleased with this treaty, those in Arkansas, where the Choctaw were to be removed, were not. People in Mississippi told them that they should accept the “burden” of the Indians until they obtained statehood and then they could force the Indians to move farther west. The editor of the Mississippi Gazette wrote:

“In the course of time, the territory of Arkansas, will also claim a state of independence, the Indians must be removed from her soil-and she will set but little importance upon the arguments now volunteered for her, against the treaty which may effect it.”

In 1824, a ten-member Choctaw delegation under the leadership of Pushmataha traveled to Washington, D.C. to protest the fact that their western allotments in Oklahoma and Arkansas are already occupied by non-Indians. In Washington, the Secretary of War provided the delegation with a whiskey allowance of $3 per day per delegate, but this proved to be inadequate. Over a period of three months, each Indian averaged $8.21 per day for whiskey.

In 1825, William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) met with the Choctaw and Chickasaw to convince them to move west. The tribal leaders tell him in no uncertain terms that they are not interested. The non-Indian citizens of Mississippi were outraged at this refusal and some demanded that the Indians be driven out by force.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. In making the case for Indian removal, Lewis Cass, the Secretary of War, wrote in the North American Review:

“A barbarous people, depending for subsistence upon the scanty and precarious supplies furnished by the chase, cannot live in contact with a civilized community.”

President Andrew Jackson stated:

“It will relieve the whole State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy; and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

Dancing Rabbit Creek:

In 1830 the Secretary of War (who is in charge of Indian affairs in the United States at this time) called the Choctaw leaders together at Dancing Rabbit Creek to negotiate a removal treaty. The United States ordered all missionaries to stay away from the council grounds under the pretext that their presence would be improper as the meeting was not a religious service, but a treaty negotiations session. The American negotiators feared that the missionaries would speak out against the treaty and convince the Choctaw, many of whom were Christian, that it was a bad deal. The missionaries complained bitterly about this decision, but to no avail.

According to the proposal which the Americans submitted to the Choctaw leadership, in removing to the west each Choctaw tribal member would receive money, farm and household equipment, subsistence for a full year, and they would be paid for all improvements made to their Mississippi lands. While the American negotiators were confident that the Choctaw would accept the treaty, the Choctaw council voted unanimously to reject it. They gave two reasons for the rejections: (1) they wanted a perpetual guarantee that the United States would never try to possess their new lands in the west, and (2) they were dissatisfied with the lands which had been offered to them in Indian territory.

In response to the Choctaw rejection of the treaty, the Americans informed the Choctaw that they must either move west or be placed under Mississippi law. Under Mississippi law they would lose their lands, receiving nothing for them. If they resisted, the Americans told them, then the American armed forces would destroy them. As a result of these threats, the Choctaw leaders and the American negotiators reached an agreement in which the Choctaw got a perpetual guarantee of their new home. Under the treaty, non-Indians were not to be allowed to enter the Choctaw nation without the consent of tribal government. The exception to this is the Indian agent who was to be appointed by the President every four years.

The removal of the Choctaw from Mississippi was to take place over a period of three years, with one group (supposedly one-third of the nation) moving west each year. By 1833, according to the treaty, the Choctaw nation would no longer be in Mississippi.

Recognizing that not all tribal members might want to move, the treaty allowed for some to remain in Mississippi. Chiefs who remained were to receive four sections of land and an annual payment of $250; adults were to receive 640 acres; children over 10, 160 acres. Indians failing to register within 6 months would be barred from registering.

In response to the treaty, Chief David Folsom said:

“Our doom is sealed. There is no other course for us but to turn our faces to our new homes toward the setting sun.”

The Removals:

In December of 1830, 400 individuals left for the west. This initial group was composed of Choctaw captains and high-ranking warriors who felt that they could sell their lands for a handsome price at this time and feared that if they delayed the land values would decrease.

A second group of about 4,000 left in 1831. They were transported by steamboat as far as possible up the Arkansas and Ouachita Rivers. They arrived at their new homes after a five month journey. Many of them were sick and all of them were exhausted and discouraged.

In 1832, the removal of the remaining Mississippi Choctaw was turned over to the army. Under orders to economize, rations were decreased and transportation was provided only for the very young and those who were very sick. Nine thousand Choctaw were removed, most of whom walked all the way to their new homes. They had no time to prepare for the trip and were told that the American government would provide all supplies. They were issued one blanket per family (there were an average of six people per family). They were forced by the government to leave during the winter and en route they encountered a snow storm. Ice flows prevented them from crossing the Mississippi River and they huddled in the freezing rain for several days. Many died of starvation and exposure. During the 350 mile forced march, in which many did not have shoes to wear, it was estimated that 2,500 died. The Choctaw were not allowed to care for the bodies of the dead in their traditional way. Instead, the Americans forced them to bury the dead in a European fashion.

Staying Behind:

Those Choctaw who wanted to remain in Mississippi under the terms of their treaty found it difficult to do so. The Indian agent was strongly opposed to having any Choctaw remain, so he simply put off registering them as long as he could. He pretended to be sick, and sometimes went into hiding. He was determined to deny the Choctaw their treaty rights. Reluctantly, he registered a few-69-so he could show at least token compliance with the terms of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.