James K. Polk was the dark horse who became President of the United States in 1845. Polk set four goals for his administration and two of these had major implications for American Indians: (1) the acquisition of the Oregon Territory, and (2) the acquisition of California and New Mexico. Polk himself had little direct contact with Indians, but the policies established during his administration had long-lasting ramifications for Indian tribes and Indian people.

During Polk’s presidency, the concept of Manifest Destiny became popular. In 1845, the New York Democratic Review wrote about

“our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

In 1846, Senator Thomas Hart Benton said:

“It would seem that the White race alone received the divine command, to subdue and replenish the earth, for it is the only race that has obeyed it-the only race that hunts out new and distant lands, and even a New World, to subdue and replenish.”

Indian Administration:

President Polk appointed William Medill as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Medill felt that Indians must be “civilized” and they had to be instructed in morality, religion, and the work ethic. Medill considered Indians to be ignorant, degraded, lazy, and possessed of no worthwhile cultural traits.

In 1846, Congress created the Smithsonian Institution to fulfill the terms of the will of James Smithson. The Smithsonian was given custody of all federal government museum collections, including collections of Indian artifacts. The Smithsonian’s regents encouraged the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to collect items which illustrated the history, manners, and customs of the Indians.

In a lecture at the inaugural meeting of the Smithsonian Board of Regents, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft pointed out that it was the task of museums to preserve the full array of artifacts produced by each Indian nation before these nations disappeared. He told the Regents:

“It is essential to the purposes of comparison, that a full and complete collection of antiquarian objects, and the characteristic fabric of nations, existing and ancient, should be formed and deposited in the Institution.”

The law creating the Smithsonian also stated that

“all collections of rocks, minerals, soils, fossils, and objects of natural history, archaeology and ethnology [made by or for the government], when no longer needed for investigations in progress shall be deposited in the National Museum.”

In 1846, St. Louis Superintendent of Indian affairs, Thomas H. Harvey, heard complaints from the Plains tribes about non-Indians wantonly destroying the buffalo. He alerted Washington to these complaints and asked for a general council with the Indians to negotiate peace treaties. He also called attention to

“the necessity of buying out a road or roads to the mountains, and paying the Indians through whose country they might pass, such compensation as the government might deem proper.”

In describing Indians in 1847, one Indian superintendent said:

“I consider them a doomed race, who must fulfill their destiny. …I will further remark that I fear the real character of the Indian can never be ascertained because it is altogether unnatural for a Christian man to comprehend how so much depravity, wickedness and folly can possibly belong to human beings… I have never been fully convinced of the propriety or good policy of admitting and acknowledging the right of Indians to the soil.”

The 1848 annual report of Indian Commissioner William Medill stressed the belief that Indians must make way for the superior race of civilized people. He characterized Indians as wedded to savage customs, prejudices, and habits; as finding labor repugn¬ant. Medill felt that education and Christianization were needed.

One of the far-reaching changes in Indian administration came in 1849 when the Office of Indian Affairs (now the Bureau of Indian Affairs) was transferred from the Department of War to the newly created Depart¬ment of the Interior.

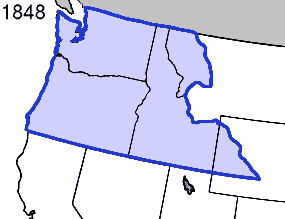

Oregon Territory:

Since 1818 the Oregon Territory (which includes present day Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming) had been jointly administered by the United Kingdom and the United States. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 set the new boundary at the 49th parallel and thus the United States acquired sole administration of the territory. The new boundary cut across many traditional Indian territories, placing part of their people under American jurisdiction and part of them under British jurisdiction.

Indian nations were not consulted about the new boundary. International law recognized that Indians held title to their land, but sovereignty was granted to the European nations – the United Kingdom and the United States, in this case — because of the “right of discovery.”

Congress passed the Oregon Organic Act in 1848 which established Oregon Territory and set the stage for statehood. The Act included five provisions dealing with Indians. The Act:

1. indicated that lands were not to be taken from the Indians without their consent and affirmed the rights of person and property for Indians.

2. granted 640 acres to occupied mission sites at the time of its enactment.

3. created the office of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the territory.

4. extended the Ordinance of 1787 to all of Oregon Territory which included the philosophical idea that Indians are to be dealt with in utmost good faith.

5. appropriated $10,000 for the purchase of presents to the tribes.

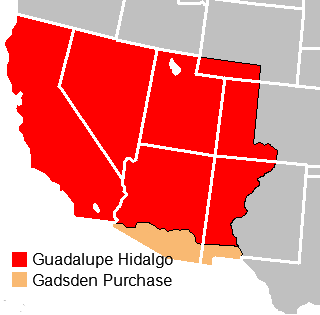

California and New Mexico:

Following the Mexican War, the United States acquired California and New Mexico through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Under this treaty, ratified in 1848, the United States acquired what would become California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico and parts of Colorado and Wyoming.

The acquisition of New Mexico by the United States brought new dangers to the Pueblos. Under Spanish and Mexico rule, the Pueblos had adopted Catholicism and had combined this with their own religious practices without any loss of the basic fabric of their life. With the American administration, however, they were faced with proselytizing Protestant Christians bent on imposing their own religion upon the Indians.

Leave a Reply