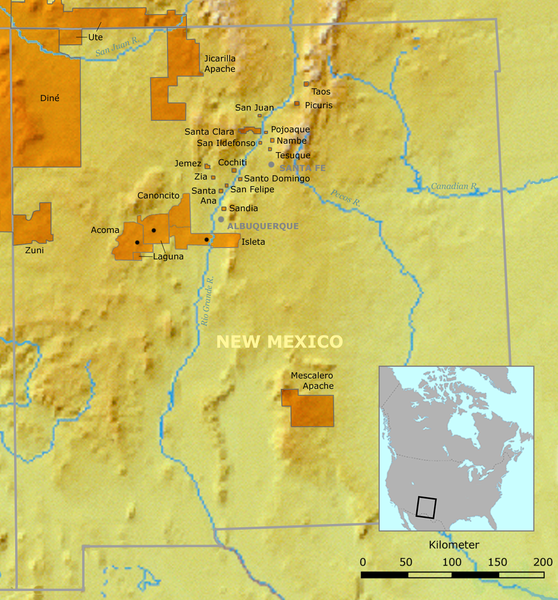

The reservation for the Jicarilla Apache Tribe was established in New Mexico by Executive Order of President Grover Cleveland in 1887. Following the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, the tribe adopted a formal constitution that provided for the taxation of members of the tribe as well as for non-members of the tribe who were doing business on the reservation.

In 1953, the tribe entered into a series of agreements with oil companies to provide oil and gas leases. The oil companies approached the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior about these leases and negotiated them with representatives from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The BIA then presented the finalized lease agreements to the tribal council, which was expected to approve them without debate.

Under the terms of the leases, the oil companies were supposed to pay royalties to the tribe. These royalties were not to be paid directly to the tribe, but were to be collected on behalf of the tribe by the BIA. The BIA was less than diligent about collecting royalties.

During the 1970s, Americans became acutely aware of the country’s dependence on foreign oil and the importance of oil to their daily lives. During this time, many American Indian leaders became more aware of the value of the oil and coal resources on their reservations. In 1975, the Council of Energy Resource Tribes (CERT) was established to improve reservation conditions, to gain inventories of resources, to serve as a clearinghouse, to use resources on reservations rather than exporting them, and to supply information on the environmental impact of resource development. Twenty-five tribes were included in CERT. CERT informed the Federal Energy Agency (FEA):

“If our energy resources are to be developed at all, they are to be developed with our informed consent and participation. ”

According to CERT:

“Historical and economic forces have combined to create these problems for the people of America and the world. We have combined to see that these same forces, which we have dealt with before under many forms other than energy, do not cause the United States to react in its historical pattern of wasteful and unlawful exploitation of Native American resources for immediate needs.”

In 1976, the General Accounting Office (GOA) found that an oil well on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation in New Mexico had been flaring gas for six months without approval. The U.S. Geological Service (USGS), the agency responsible for monitoring the oil wells, was unaware of the flaring as their inspectors had not been out in the field. USGS relied upon industry to inform it of problems.

The Jicarilla Apache filed suit against oil producers on their reservation, noting the failure of the Department of the Interior to exercise its fiduciary responsibilities. Had the Secretary of the Interior simply ordered the oil companies to perform as required by their leases this lawsuit could have been avoided. While the tribe was successful in its litigation, the Department of Interior opposed the tribe in the litigation. As the tribe’s trustee, the Secretary of the Interior would not approve the settlement agreements until the tribe agreed to dismiss their claims against the Secretary.

In 1976, the Jicarilla Apache enacted a tax ordinance to impose a severance tax on mineral development companies. The tax, which was on oil and natural gas severed, saved, or removed from tribal lands, was only 29 cents per barrel and had little impact on consumers. However, New Mexico’s newspapers were filled with derisive letters and editorials criticizing the idea of a little Indian tribe taxing non-Indians.

Major oil companies responded to the Jicarilla Apache tax by filing suit against the tribe, claiming that they were not subject to tribal jurisdiction and should not be subject to double taxation by the tribe and the state. The District Court ruled against the tribe finding the tribal tax to be “illegal, unconstitutional, invalid, and void.” The tribe appealed.

In 1979, the ruling of the District Court was overturned by the Tenth Circuit Court which found that the tribe had the inherent power under tribal sovereignty to impose taxes on the reservation. The oil companies responded by appealing immediately to the U.S. Supreme Court. CERT and the Navajo Nation filed briefs supporting the Jicarilla Tribe.

In 1982, the Supreme Court in Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe ruled that the tribe could both receive royalties on oil and gas leases as a property owner and tax oil and gas companies as a sovereign power. According to the Court:

“sovereign power, even when unexercised is an enduring presence that governs all contracts subject to the sovereign’s jurisdiction, and will remain intact unless surrendered in unmistakable terms.”

The Court also said:

“The power to tax is an essential attribute of Indian sovereignty because it is a necessary instrument of self-government and territorial management.”

The Court also ruled that the way in which a reservation was established – by treaty or by executive order – did not affect the tribe’s sovereign power. The Court noted that only the Federal Government may limit a tribe’s sovereign authority.

Immediately following the decision by the Supreme Court, the BIA proposed new regulations which would have severely limited the ability of Indian tribes to impose severance taxes. The tribes complained about the proposed regulations and the BIA eventually dropped them. The very fact that the BIA proposed these new rules, however, showed that the BIA was more concerned with the welfare of the oil companies than with the welfare of Indians.

Looking toward the future, the Jicarilla Apache Tribe in 1977 bought the interest of Palmer Oil Company on the reservation. The Jicarilla Apache became the first tribe in the country to own and operate producing oil and gas wells on its reservation.

Leave a Reply