Traditionally the United States has assumed that any mineral and energy resources found on Indian reservations should be developed by non-Indian private enterprise and that Indians should benefit as little as possible from these resources. The role of the federal government in developing these resources has been to help private enterprise obtain mineral and energy resources from Indian nations. One example of this can be seen in corporate attempts to develop oil resources on the Navajo Reservation in the 1920s.

First, some background: the administration of Indian reservations in the United States comes under the Department of the Interior. The Bureau of Indian Affairs-which was called the Indian Office in the 1920s-is a part of the Department of the Interior. Both the Secretary of the Interior and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs are political appointments.

In 1921, Albert Fall, the former Senator from New Mexico, was appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Warren Harding. Fall was hostile to Indian rights and felt that large tracts of Indian land inhibit progress. Fall would later become involved with the Teapot Dome scandal and would be jailed for his misconduct in oil leasing.

In 1921, prospectors combed the Navajo reservation looking for promising places for oil. However, the San Juan Navajo council did not wish to consider any oil and gas leases. In an effort to force the Navajo to issue the oil leases, the assistant commissioner of Indian affairs ordered the Indian agent to call the council together again, but once again they refused all petitions for leases. The oil companies refused to accept the Navajo decision to deny them access to the potential oil reserves. Once again the oil companies appealed to the Indian Office to look out for their interests and in response the Indian Office ordered another meeting with the San Juan Navajo. This time the oil company promised to hire Navajo for all unskilled work. Reluctantly, the Navajo agreed to a lease.

The following year, the Indian Office ordered the agent for the San Juan Navajo district to summon a council to consider more oil leases. The Navajo unanimously said “no” to any more leases, but the oil companies immediately submitted new applications with the Indian Office. The Indian Office then informed the agent that they wanted the leases approved and recommended that the agent ask the Navajo to delegate to him the authority to negotiate the leases. Again the Navajo were assembled and great pressure put on them to agree to the oil leases. The Navajo agreed to grant one lease for Tocito, but refused all others.

In response to the discovery of oil on the Navajo Reservation and the refusal of the Navajo to agree to leases with oil companies, in 1922 Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall ruled that Indian reservations which were created by Presidential Executive Order (as opposed to those created by treaty) were open to oil exploration. This removed Indians from any control over the leasing of these lands and deprived them of all but one-third of the royalties from oil leases. The ruling also made Indian title to these lands uncertain with the presumption that these reservations were “merely public lands temporarily withdrawn by Executive Order for use by Indians.”

Concerned about the need for oil companies to develop wells on Navajo land and the opposition of the Navajo to these oil wells, in 1923 the federal government unilaterally replaced the traditional Navajo council of elders with a Grand Council composed of government-selected individuals. While the new council was to be composed of delegates elected by each of the six jurisdictions on the reservation, delegates could be appointed if there was no election. The Indian Office could also remove or replace any delegates, particularly if these delegates opposed any proposals by the federal government.

All members of the Council were Navajo who had been educated off of the reservation. The Council could meet only in the presence of the Indian agent for the Navajo Tribe. With regard to this new form of government, former Navajo chairman Peter MacDonald noted:

“For the first time in the history of the Navajo Nation, the idea of a single leader was created. A twelve-member tribal council was established whose representa¬tives were to replace the traditional extended family leaders.”

The new Council, the only Navajo government recognized by the U.S. government, quickly signed leasing permits with non-Indian companies. It was clear that the United States did not want a self-governing Navajo Nation, but wanted a puppet government which could be called at its behest to negotiate on behalf of the tribe in matters of property. The new council had been established to serve the interests of the oil companies and thus did not respond to the needs and problems of local communities.

Chee Dodge, a wealthy stockman, was elected as Chairman. A split soon developed in the council. Dodge, a Catholic, felt that the royalties belonged to all of the Navajo and should be used to buy land for the impoverished Navajo stockmen. Another group, under the leadership of Jacob C. Morgan, a fundamentalist Protestant missionary, felt that traditionalists such as Dodge were not qualified to lead. Under Dodge’s leadership the council gave the Indian agent the power of attorney to negotiate and sign all leases on behalf of the tribe.

The oil leases did generate some money for the Navajo, but this money was collected by the federal government and supposedly held for them in the Treasury Department. In 1926, the Navajo found out that money from their oil leases had been earmarked to build a bridge across the San Juan River at Lee’s Ferry. The bridge was not intended for Navajo use, but it would open up a convenient automobile route to the Grand Canyon for tourists and would thus greatly benefit the Fred Harvey Company which owned the concessions in the national park.

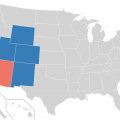

The Navajo also found out that they had been charged for several off-reservation bridges, for bridge repairs, and for building a road from Gallup, New Mexico to Mesa Verde, Colorado.

In 1926, the Navajo Tribal Council voted to set aside 20% of its oil revenues to purchase land. The following year, Chee Dodge, the Chairman of the Navajo Tribal Council, asked the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for $1 million to buy land. The money was to come from the royalties paid for Navajo oil and mineral leases. This was not taxpayer money, but money generated from private corporations. However, Congress, who controlled all tribal funds including royalties, balked at releasing the money.

In 1928, Congress authorized $1.2 million for Navajo land purchases. This action had strong opposition from the New Mexico Congressional delegation.

In 1929, the Navajo requested information on their oil royalty figures. They found that the government had failed to monitor production or obtain accurate royalty figures. Part of the problem stemmed from keeping oil records in two different offices: production and royalty reports were kept in the San Juan area superintendent’s office while operations registers were at the Bureau of Mines office in Shiprock. Furthermore, the oil companies set up sophisticated internal operations to allow them to buy and sell crude oil to themselves and thus to juggle figures at will. While it was obvious that the government was not protecting Navajo interests and that oil companies were openly defrauding the tribe, no steps were taken to correct the problem and the same system of record-keeping would continue for the next century or so.

In what seems to have been a response to Navajo requests for information, the oil companies laid off more Navajo workers than non-Indian workers. When the Navajo complained to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, he told them that all the oil companies had to do was to pay their royalties. The Navajo, however, insisted that their lease agreement called for the companies to employ Navajo workers. In addition, the companies were failing to protect the land, especially from pipeline leaks. The Indian Office and the Department of the Interior continued to support the oil companies.

While the administration of Indian affairs changed dramatically when Franklin Roosevelt became President, the conflicts between the Navajo and the oil companies were not resolved. While Roosevelt’s policies seemed to emphasize tribal self-government, the Navajo have continued to be skeptical of the government’s motivations.

Leave a Reply